About this course:

This course provides an overview of the pathophysiology and causes of and risk factors for acute myocardial infarction (AMI). It also explores the current AMI diagnostic and treatment guidelines according to the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Finally, this course will review postdischarge care recommendations for AMI patients.

Course preview

Acute Myocardial Infarction

This course provides an overview of the pathophysiology and causes of and risk factors for acute myocardial infarction (AMI). It also explores the current AMI diagnostic and treatment guidelines according to the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Finally, this course will review post-discharge care recommendations for AMI patients.

Upon completion of this module, learners should be able to:

- discuss the pathophysiology, causes, and risk factors of AMI

- explore the diagnostic process for AMI

- describe the evidence-based treatment guidelines for AMI

- review the postdischarge care recommended for AMI patients, including the top ten primary prevention techniques recommended by the ACC and AHA

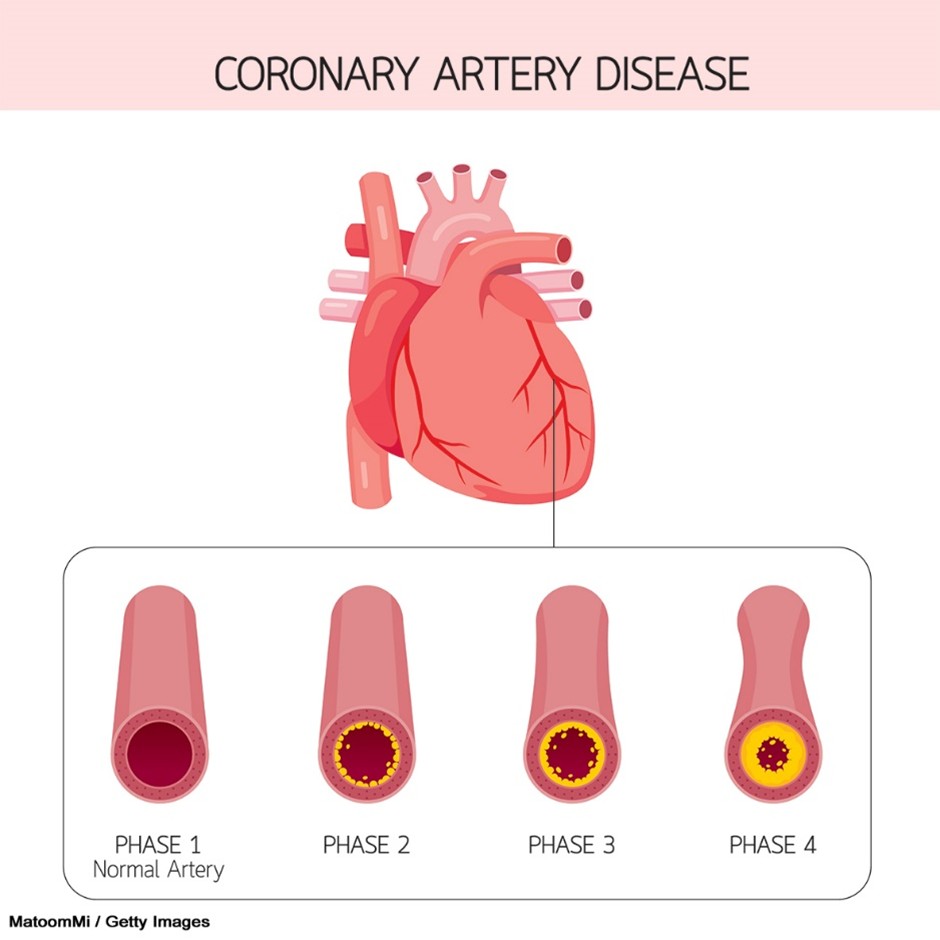

An acute myocardial infarction (AMI), commonly referred to as a heart attack, occurs when there is an acute obstruction of a coronary artery, leading to impaired blood flow and resulting ischemia, which causes irreversible tissue necrosis within the myocardium. Coronary artery disease (CAD), which is the leading cause of an AMI, is also the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. In the United States, CAD is the most common type of heart disease, resulting in 371,506 deaths annually. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 805,000 AMIs occur annually in the United States, 605,000 of these being in individuals who have no previous history of AMI, and 200,000 occurring in individuals who have previously had an AMI. In the United States, there is an AMI every 40 seconds, and 20% of heart attacks are considered silent (i.e., the damage is done, but the person is unaware). Heart disease is a frequent cause of hospital admissions in the United States and is associated with significant mortality and morbidity. Survivors of AMI are at increased risk for recurrent cardiovascular events, which place a significant cost burden on the health care system. It is estimated that heart disease costs $417 billion annually due to the costs of health care services, medications, and lost productivity (Byrne et al., 2023; CDC, 2024a, 2024b; Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Physiopedia, n.d.; Sweis & Jivan, 2024).

Anatomy and Physiology

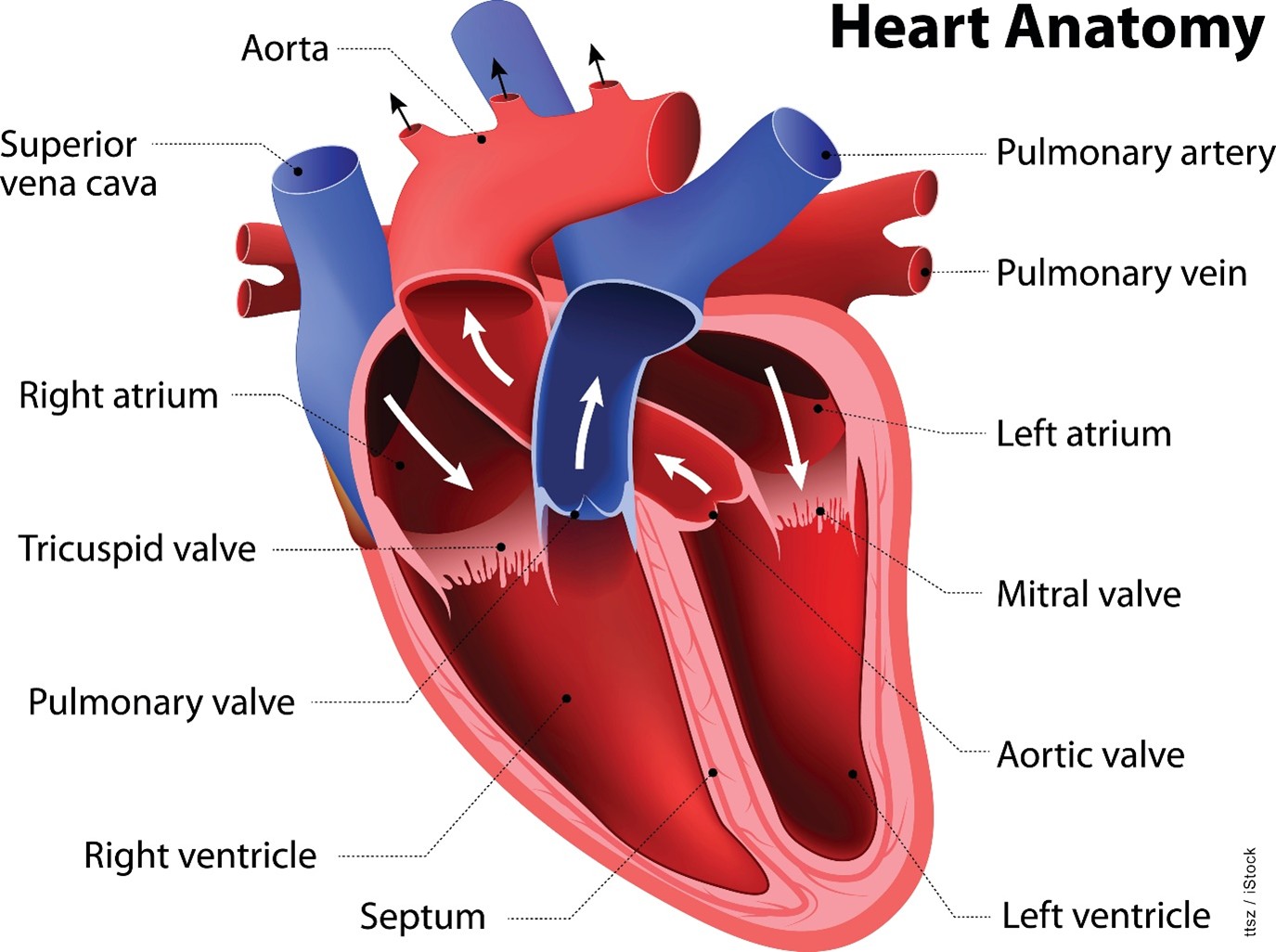

The heart is a strong, muscular pump that circulates blood throughout the body. The heart beats approximately 100,000 times daily and pumps 2,000 gallons of blood. The heart consists of four chambers: the right atrium, which accepts deoxygenated blood from the body via the veins; the right ventricle, which pumps that deoxygenated blood to the lungs via the pulmonary artery; the left atrium, which accepts newly oxygenated blood from the pulmonary veins; and the left ventricle, which pumps oxygenated blood to the rest of the body via the aorta. Four one-way, pressure-activated valves separate these four chambers. The tricuspid valve is a three-flap valve that separates the right atrium from the right ventricle. The pulmonary valve is a three-flap valve that separates the right ventricle from the pulmonary artery. The mitral valve is a double-leaflet valve that separates the left atrium from the left ventricle and may also be called the bicuspid valve because of its construction. Finally, the aortic valve is a three-flap valve that separates the left ventricle from the aorta (refer to Figure 1; AHA, 2024; Hinkle et al., 2025).

Figure 1

Anatomy of the Heart

Pathophysiology of AMI

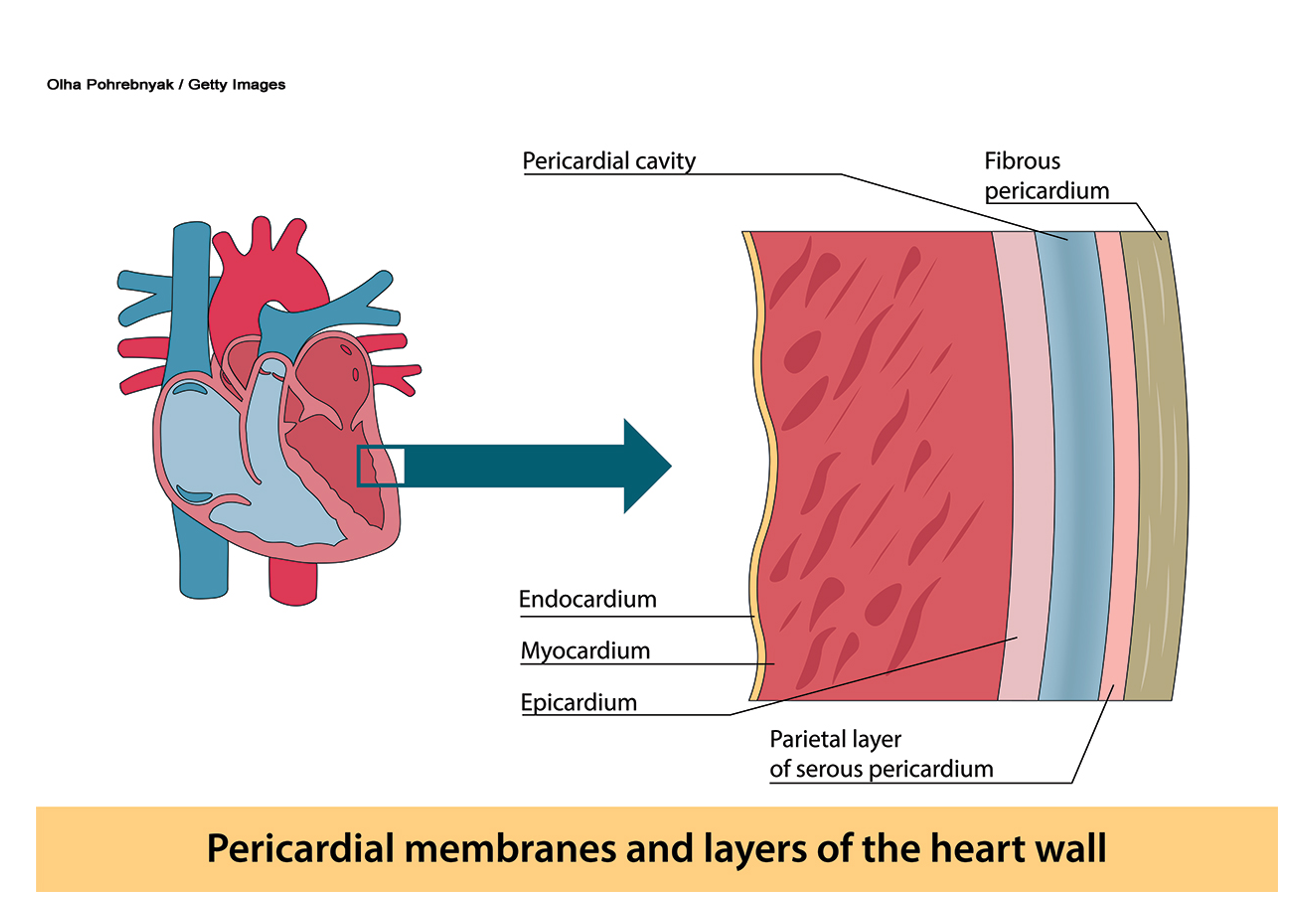

An AMI, or type 1 spontaneous MI, indicates irreversible myocardial injury resulting in tissue necrosis of a significant portion (generally greater than 1 cm) of the myocardium, the heart’s muscular tissue (refer to Figure 2). “Acute” denotes an infarction that is less than 5 days old. During this time, the inflammatory infiltrate consists primarily of neutrophils. AMIs may be of the nonreperfusion type, indicating that the obstructed blood flow is permanent, or of the reperfusion type, indicating that the lack of blood flow is sufficiently prolonged (typically hours) to induce cell death but is later reversed or restored (Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2024; Urden et al., 2021).

Figure 2

Layers of the Heart Wall

AMIs generally affect a segment or region of the myocardium secondary to the occlusion of an epicardial artery (refer to Figure 2). This segment or region is typically endocardium-based. In contrast, concentric subendocardial necrosis (necrosis of the inner layer of the heart, the endocardium, and the inner portion of the myocardium) may result from global ischemia and reperfusion in cases of prolonged cardiac arrest with resuscitation. Areas of MI may be subepicardial (affecting the outer portion of the myocardium and epicardium) if there is thromboembolic occlusion of smaller vessels originating from coronary thrombi. Obstructive CAD can be found in most patients through angiography (Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2024; Urden et al., 2021).

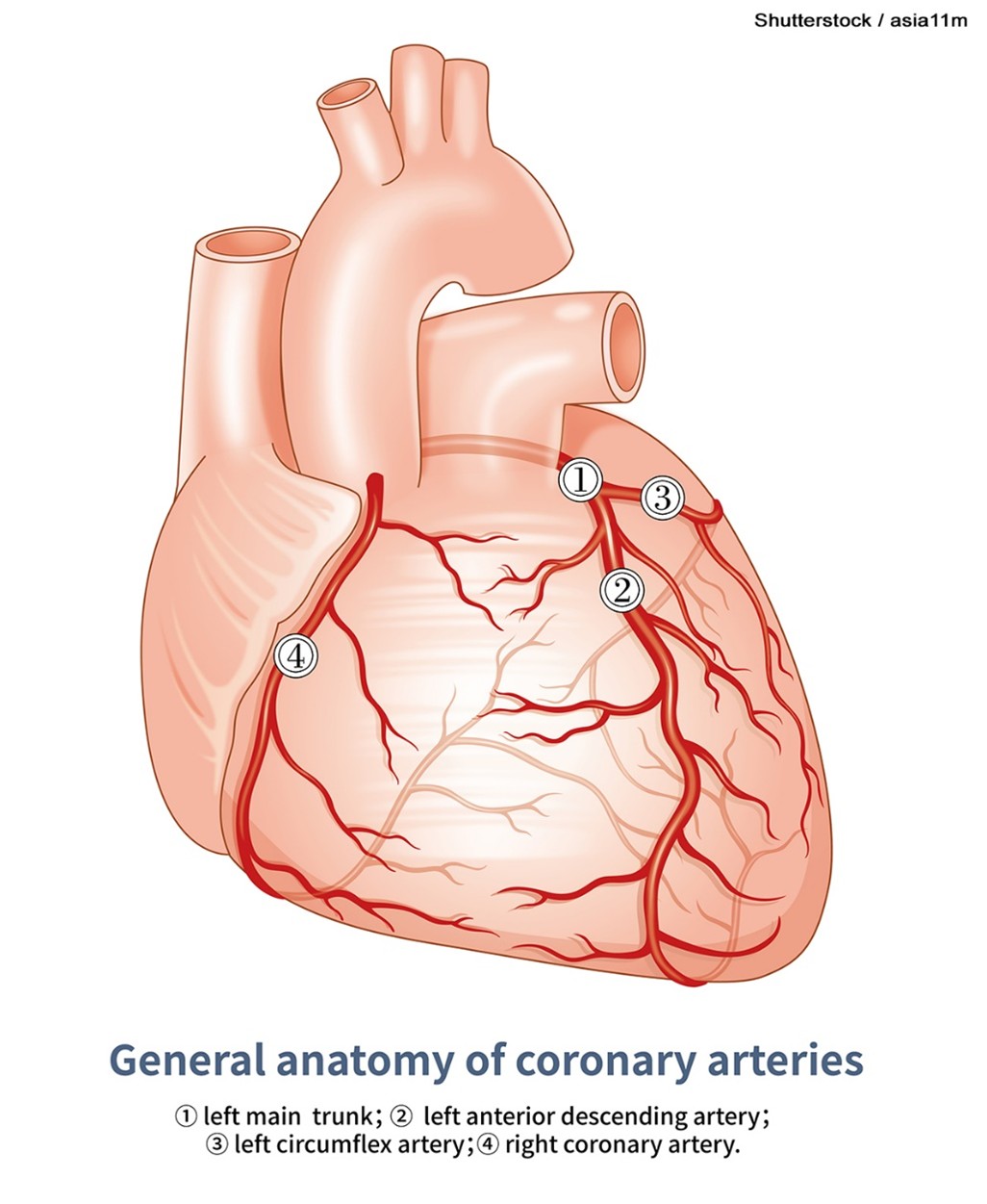

The infarct area occurs in the occluded vessel’s distribution (refer to Figures 3 and 4). Left main coronary artery occlusions generally result in a large anterolateral infarct, whereas occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery causes necrosis limited to the anterior wall. There is often an extension to the anterior portion of the ventricular septum with proximal left coronary occlusions. In individuals with a right coronary dominance (i.e., the right artery supplies the posterior descending branch), a right coronary artery occlusion causes a posterior inferior infarct, and a proximal obtuse marginal thrombus will cause a lateral wall infarct. With a left coronary...

...purchase below to continue the course

Figure 3

Main Coronary Arteries

Figure 4

Coronary Artery Disease

Causes of Acute Angina and AMI

AMIs happen when the blood supply to the heart muscle has been obstructed. In most cases, it is an acute event resulting from the sudden rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary artery wall in a person with typical CAD, the leading cause of AMIs (Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2024; Urden et al., 2021). AMIs occur most often early in the morning, possibly due to circadian variations in sympathetic tone. The most common conditions that may lead to an AMI include the following (Sweis & Jivan, 2024, 2025c; Urden et al., 2021):

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) associated with typical CAD is, by far, the most common cause of an AMI. It may lead to unstable angina, ST-elevation MI (STEMI), or non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI).

- Coronary artery spasms (otherwise known as Prinzmetal angina) can lead to myocardial ischemia if they persist for prolonged periods. However, the duration of angina is typically less than that of other forms of angina.

- Microvascular angina (formerly cardiac syndrome X) occurs within the smaller cardiac vessels and may lead to an AMI.

- Stress cardiomyopathy (broken heart syndrome) occurs due to stressful life events, causing endothelial tissue dysfunction that can lead to heart failure (HF).

- Viral myocarditis is an infection directly affecting the heart muscle. It produces extensive localized inflammation in the cardiac muscle, interrupting the local blood supply.

- Blood clotting disorders, such as factor V Leiden, can lead to the acute thrombosis of a coronary artery without underlying CAD and, subsequently, AMIs.

- A coronary artery embolism, usually originating within a heart chamber, dislodges and obstructs a coronary artery, interrupting the blood supply to part of the heart muscle. Several conditions predispose a person to embolism formation, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), dilated cardiomyopathy, and the presence of prosthetic heart valves.

Risk Factors for Atherosclerosis

AMIs occur due to decreased coronary blood flow, often attributed to atherosclerosis. The risk of early-onset AMIs tends to have a genetic link. Evidence of familial hypercholesterolemia or factor V Leiden places patients at higher risk for CAD and cardiac events. There are various modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for atherosclerosis. Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, individuals assigned male at birth, family history of premature CAD, and the presence of male-pattern baldness (Mechanic et al., 2023; Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025d). The vast majority of risk factors are modifiable and include the following:

- smoking/tobacco use

- hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and dyslipidemia

- diabetes mellitus (DM)

- hypertension

- elevated body mass index (BMI), as well as abdominal circumference

- psychosocial factors (e.g., depression, anxiety, and stress)

- sedentary lifestyle

- a diet lacking fruits and vegetables

- poor oral hygiene

- anxiety

- elevated homocysteine level

- alcohol consumption

- peripheral vascular disease (Mechanic et al., 2023; Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025d)

Other causes of AMIs include trauma, substance use (e.g., cocaine), aortic dissection, vasculitis, coronary artery anomalies, coronary artery emboli, and excessive demand on the heart (e.g., anemia, hyperthyroidism; Mechanic et al., 2023; Wilson, 2025). Tables 1 and 2 review the classes of recommendations and level of evidence used in the ACC, AHA, as well as the ESC guidelines for the management of patients with STEMI/NSTEMI (Byrne et al., 2023; Jneid et al., 2017). The class of a recommendation indicates its strength, while the level of evidence refers to the quality of the support for a recommendation (Byrne et al., 2023).

Table 1

Classes of Recommendations

Classes of Recommendations | Definition | Suggested Wording |

Class I | Evidence/general agreement shows a given treatment or procedure is beneficial, useful, and effective. | Is indicated/recommended |

Class II | Conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion support the usefulness/efficacy of the given treatment or procedure. | N/A |

Class IIa | The weight of evidence/opinion is in favor of usefulness/efficacy. | Should be considered |

Class IIb | Usefulness/efficacy is less established by evidence/opinions. | May be considered |

Class III | Evidence or general agreement shows the given treatment or procedure is not useful/effective and, in some cases, may be harmful. | Is not recommended |

(Byrne et al., 2023)

Table 2

Levels of Evidence

Level of Evidence A | Data derived from multiple random clinical trials or meta-analyses |

Level of Evidence B | Data derived from a single random clinical trial or large nonrandomized studies |

Level of Evidence C | A consensus of experts or small studies, retrospective studies, and registries |

(Byrne et al., 2023)

Diagnosis of AMI

The first step in diagnosing an AMI is identifying the presenting symptoms, which include persistent, intense, substernal chest pain that lasts at least 30 minutes and classically radiates to the neck, jaw, shoulder, or left arm. A history of CAD should increase the suspicion of an AMI. Chest discomfort—especially pressure described as squeezing, aching, burning, or sharp—is also common. Less typical symptoms may include shortness of breath; nausea/vomiting; fatigue; palpitations; malaise; lightheadedness/syncope; coughing; wheezing; profuse sweating; or epigastric feelings of fullness, indigestion, or gas. Individuals assigned female at birth tend to present with atypical symptoms more often than individuals assigned male at birth and usually develop atherosclerotic disease 7–10 years later than those assigned male. Vital sign assessment usually indicates tachycardia with or without an arrhythmia, tachypnea, and elevated blood pressure (Reeder & Kennedy, 2025a, 2025b; Reeder & Mahler, 2025). Patients with a right ventricular AMI or severe left ventricular dysfunction may present with hypotension and cardiogenic shock symptoms (i.e., shortness of breath, clammy skin, fever, loss of consciousness, and edema in the lower extremities; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2022). A resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is the first-line diagnostic tool. It should be obtained and interpreted by a qualified provider within 10 minutes of the patient’s first medical contact, according to the 2023 ESC guidelines and the 2025 ACC/AHA/American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP)/National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians (NAEMSP)/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI; Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025).

The ACC/AHA recommends the use of a validated risk stratification tool, especially for NSTEMI patients, such as the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk index or the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk model (Jneid et al., 2017). Early risk stratification in patients with ACS is critical to identify patients at high risk for future cardiac events, who would benefit from more aggressive treatment. Clinical trials have identified the presence and extent of ST-segment depression, elevated cardiac biomarkers, hemodynamic instability, and persistent chest pain despite treatment as factors predicting high risk. These factors were used to create the TIMI and GRACE risk tools. The TIMI tool has seven risk factors that receive a score of 1 if present and 0 if absent; overall scores of 0–2 are low risk, 3–4 are intermediate risk, and 5–7 are high risk (Simons & Breall, 2025). The TIMI factors include:

- age of 65 and older

- presence of at least three risk factors for CAD (e.g., hypertension, DM, smoking, dyslipidemia)

- prior coronary stenosis of 50% or greater

- at least two anginal episodes in the previous 24 hours

- use of aspirin in the past 7 days

- elevated serum cardiac biomarkers

- presence of ST-segment deviation on admission ECG (Simons & Breall, 2025)

The GRACE risk tool includes eight parameters to predict death and AMI in the hospital, including heart rate, age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), creatinine, cardiac arrest, ST-segment deviation, elevated cardiac enzyme markers, and Killip Class congestive HF (a classification system used for individuals who have had an AMI). The GRACE tool has slightly better predictability than the TIMI (Simons & Breall, 2025).

ECG monitoring should be initiated as soon as possible when an AMI is suspected to establish a baseline rhythm, assess for arrhythmias, and allow immediate treatment. AMIs are classified into those that cause STEMI on ECG and those that do not (i.e., NSTEMI). The ECG tracings in Figure 5 illustrate ST-segment elevation in anterior leads (highlighted in orange) and ST-segment depression in inferior leads (highlighted in blue). The earliest changes in an STEMI are the development of a hyperacute or peaked T wave that reflects localized hyperkalemia, although this finding is not frequently seen. Subsequently, ST-segment elevation occurs in the leads monitoring the electrical activity of the involved region of the myocardium. Initially, there is elevation of the J point, and the ST segment retains its concave appearance, and over time, the ST elevation becomes more pronounced, convex, and rounded upward. Eventually, the ST segment becomes indistinguishable from the T wave. The ESC, ACC, AHA, and World Heart Federation (WHF) committee defines a STEMI based on the following ECG criteria: at least a 2.5 mm elevation in the ST segment in at least two contiguous leads for individuals assigned male at birth who are under 40 years of age and at least 2 mm for those over 40. For individuals assigned female at birth, the ESC defines a STEMI as an elevation of at least 1.5 mm in leads V2-V3 or 1 mm in all other leads. The ESC/ACC/AHA/WHF also established the definition for an NSTEMI to include a new horizontal or downsloping ST depression of 0.5 mm or greater in two contiguous leads and/or T inversion greater than 1 mm in two contiguous leads with a prominent R wave or R/S ratio of greater than 1. The right precordial leads (V3R and V4R) should be monitored for patients with suspected inferior AMI, as a right ventricular infarct (defined as a 1 mm or greater ST-segment elevation in V3R or V4R) is found in roughly one-third of inferior AMIs. Management for these patients is often complicated, so this finding is significant (Byrne et al., 2023; Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025a; Thygesen et al., 2018).

The 2017 ACC/AHA Measure Set also defines “STEMI equivalent” findings on ECG as hyperacute T-wave changes or multilead ST-segment depression in combination with an elevation in lead aVR. Severe obstruction without a major coronary artery occlusion usually results in NSTEMI (Jneid et al., 2017). A combination of at least 0.5 mm of ST-segment depression and a positive terminal (inverted) T wave (especially in leads V1-V3) can indicate myocardial ischemia corresponding to the left circumflex artery. An isolated posterior AMI affecting the inferior/basal territory of the heart can be confirmed in these patients with concomitant elevation of at least 0.5 mm in leads V7-V9. Obstruction of the left main coronary artery may present as hemodynamic instability coupled with ST-segment depression greater than 1 mm in eight or more surface leads, along with ST-segment elevation in aVR and/or V1. Bundle branch blocks (BBB) and pacemakers can pose challenges in the diagnosis of an AMI. Diagnosing patients with left BBB is difficult unless marked ST-segment changes are present. Right BBB makes it difficult to detect transmural (affecting the entire thickness of the myocardium, spreading from the subendocardium to the epicardium) ischemia. The presence of a pacemaker and ACS symptoms may require urgent angiography to confirm the diagnosis and begin therapy. Some patients present without ST-segment changes initially, although hyperacute T-waves may be an early sign. If symptoms persist, ECG monitoring should be repeated with consideration of extension into leads V7-V9. This is more common in patients with left main disease, acute occlusion of a vein graft, and occluded circumflex coronary artery (Byrne et al., 2023; Goldberger, 2024; Goldberger & Prutkin, 2024; Reeder & Mahler, 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2024).

Figure 5

ST Elevation Versus Depression

The term AMI should be used only when there is evidence of myocardial injury, which is defined as an elevation of cardiac troponin I (cTn) values. At least one value should be above the 99th percentile upper reference limit with necrosis in a clinical setting consistent with myocardial ischemia. The ACC/AHA Measure Set recommends cTn measurement at the initial presentation and 3–6 hours after symptom onset. The 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guidelines recommend a high-sensitivity cTn (hs-cTn) on initial presentation when available, with a repeat hs-cTn test completed 1–2 hours after the initial test. Troponins are measured using a venous blood sample. They are highly sensitive and specific for diagnosing myocardial necrosis as they are components of the cell contractile apparatus between myosin and actin. Additional cTn levels (beyond 6 hours) are recommended for patients with normal initial cTn levels but with suspicious symptoms or ECG findings. Elevated levels of cTn can be detected 2–4 hours after an ischemic cardiac event and remain elevated for up to 14 days. However, sensitivity is low in the first 6 hours of symptoms. Many emergency departments have point-of-care devices that can detect cardiac enzymes in blood within seconds (Byrne et al., 2023; Jneid et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2025; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025a; Reeder & Mahler, 2025; Thygesen et al., 2018; Urden et al., 2021).

Previously, cardiac enzyme panels included creatinine kinase (CK), creatinine kinase myocardial B fraction (CK-MB), and myoglobin. However, cTn is the only biomarker recommended for AMI diagnosis per the ESC and ACC due to its superior sensitivity and specificity. In the past, patients with normal CK-MB levels, despite elevated cTn, were diagnosed with unstable angina or minor myocardial injury. The current recommendations now classify patients with a sufficiently elevated cTn level (even a single level above the established cutoff) as having an NSTEMI. Some institutions may still use other markers to establish a diagnosis or monitor for additional tissue ischemia or necrosis over time. The initiation of treatment does not depend on cardiac markers. Current ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that patients with ACS symptoms on presentation and ST-segment elevation on ECG receive treatment immediately, regardless of cTn results. Additional testing for patients with a suspected AMI includes a complete blood count (CBC), a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and a lipid profile (Gursahani, 2021; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025a; Sweis & Jivan, 2024).

Coronary angiography is often combined as a diagnostic tool with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Timely angiography and PCI have been shown to decrease morbidity and mortality significantly. Another ECG should be obtained in cases of symptom relief after nitroglycerin (Nitrostat, NitroMist, NTG). Complete normalization of the ST-segment elevation, along with symptom relief, is suggestive of coronary spasms without associated MI. Providers should obtain an early coronary angiography within 24 hours in cases like these. In cases with recurrent episodes of ST-segment elevation or chest pain, immediate angiography is required (Byrne et al., 2023). Refer to Table 3 for clinical recommendations on diagnosing AMI from the ESC.

Table 3

Recommendations for Initial Diagnosis of AMI From the ESC

Recommendations | Class | Level |

Diagnosis and initial risk stratification of ACS should be based on clinical history, symptoms, vital signs, and other physical findings, ECG, and hs-cTn. | I | B |

A 12-lead ECG should be obtained within 10 minutes. | I | B |

ECG monitoring with defibrillator capacity should be initiated as soon as possible for suspected STEMI. | I | B |

For an inferior wall AMI or total vessel occlusion, use additional right precordial leads (V3R, V4R, and V7-V9) to identify right ventricular infarction. | I | B |

An additional 12-lead ECG is recommended in cases with recurrent symptoms and diagnostic uncertainty. | I | C |

Hs-cTn should be drawn immediately after presentation and results obtained within 60 minutes. A repeat hs-cTn should be drawn in 1–2 hours. Additional testing after 3 hours is recommended if the first two hs-cTn measurements are inconclusive. | I | B |

Established risk scores (e.g., GRACE) should be used for prognosis estimation. | Iia | B |

Immediate triage for emergency reperfusion is recommended for patients with suspected STEMI. | I | A |

(Byrne et al., 2023)

Treatment Guidelines for AMI

Prehospital Care and Symptom Relief

Patients with ACS symptoms who are initially managed by emergency medical services (EMS) should have intravenous (IV) access established. A common acronym that prehospital providers previously used to recall the appropriate initial treatment for AMI is MONA, consisting of morphine (Duramorph), oxygen, nitroglycerin (Nitrostat, NitroMist, NTG), and aspirin (ASA). Recent evidence has found that elements of MONA may not be helpful and instead could be harmful. For example, some studies have found that patients who received morphine (Duramorph) within 24 hours of an AMI had a higher mortality rate and larger areas of tissue damage. The use of oxygen in some patients could reduce blood flow to the heart. An acronym that has been suggested to replace MONA is THROMBINS2, which retains some of the original components of MONA. The THROMBINS2 acronym stands for thienopyridines, heparin, renin-angiotensin system blockers, oxygen therapy, morphine (Duramorph), beta-blockers, intervention (or invasive surgery), nitrate, and statins and salicylate (aspirin, ASA; ACLS.com, n.d.; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025b).

The 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guidelines for prehospital management for patients with suspected AMI recommend that EMS transport these patients directly to PCI-capable hospitals with the goal of first medical contact to PCI of 90 minutes or less. EMS providers should notify the receiving facility to reduce the time to perfusion. Supplemental oxygen has historically been part of routine care for patients with suspected AMI. Recent research has not demonstrated a benefit in patients without hypoxia. The 2025 guidelines recommend that supplemental oxygen be administered if pulse oximetry readings indicate decreased oxygen saturation (SaO2; less than 90%) to improve myocardial oxygen supply and decrease anginal symptoms. Routine administration of supplemental oxygen is not recommended for patients with an SaO2 above 90% (Rao et al., 2025; Reeder & Mahler, 2025).

Patients experiencing an AMI often experience chest pain. Rapid and effective pain relief is important to prevent sympathetic activation and adverse clinical sequelae. Nitrates and opiate medications are effective treatment options but should be used cautiously to prevent harm. Nitroglycerin (Nitrostat, NitroMist, NTG) works as a systemic vasodilator to reduce the venous return and, subsequently, the workload of the heart; it can be given using sublingual tabs at 0.3–0.4 mg or 1–2 sprays sublingually every 5 minutes with up to 2 repeat doses. Nitroglycerin (Nitrostat, NitroMist, NTG) should be used only in hemodynamically stable patients, with an SBP above 90 mm Hg. Patients should be monitored for hypotension and headache. Analgesic therapies can provide symptomatic relief but have not been shown to improve clinical outcomes in patients with ACS. Morphine (Duramorph) is typically dosed at 2–4 mg and given intravenously. This dosing can be repeated every 5–15 minutes until relief is achieved; doses up to 10 mg may be considered. Morphine (Duramorph) may delay the effects of oral P2Y12 (platelet receptor for adenosine diphosphate [ADP] therapy. Patients should be monitored for hypotension, vomiting, or respiratory depression. Fentanyl (Sublimaze) can also be administered for pain relief. Fentanyl (Sublimaze) is typically dosed at 25–50 mcg and may be repeated if needed. Doses of up to 100 mcg can be considered. Fentanyl (Sublimaze) may delay the effects of oral P2Y12 therapy. Patients should be monitored for hypotension, vomiting, or respiratory depression (Rao et al., 2025; Reeder & Mahler, 2025).

The ACC/AHA (Jneid et al., 2017) performance measures recommend oral chewable non-enteric-coated aspirin (ASA) administration at the initial presentation, except for patients with significant hypersensitivity or gastrointestinal intolerance, who should be given a loading dose of clopidogrel (Plavix). Refer to Table 4 for additional details regarding the dosing and duration of aspirin (ASA) for STEMI and NSTEMI patients according to the ACC/AHA recommendations. If an ECG can be obtained by EMS personnel indicating ST-segment elevation, the ESC recommends that fibrinolytic therapy be given in a prehospital setting when possible to shorten the time to treatment; prehospital fibrinolysis is not common practice in the United States (Byrne et al., 2023; Jneid et al., 2017; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025b).

Symptomatic relief—pain, breathlessness, and anxiety—is a significant concern for patients with AMI. Table 5 illustrates the ESC recommendations for symptom management (Byrne et al., 2023; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025b).

Table 4

The ACC/AHA Performance Measures for STEMI/NSTEMI Patients

Performance Measure Set | Clinical Recommendations |

| Aspirin for STEMI patients:

For NSTEMI-ACS patients:

|

2. Aspirin at discharge | STEMI: Aspirin (75–100 mg) should be continued indefinitely after PCI, and clopidogrel 75 mg daily should be continued for 2 weeks (Class I, A) and up to 1 year for patients who have fibrinolytic therapy (Class I, C) NSTEMI: After PCI, aspirin should be continued indefinitely; the maintenance dose should be 81 mg daily for patients treated with ticagrelor (Brilinta) and 81–325 mg daily for all other patients (Class I, A) |

3. Beta-blocker at discharge | STEMI: For patients without contraindications for use, beta-blockers should be continued (Class I, B) NSTEMI: For patients with stabilized HF and reduced systolic function, beta-blocker therapy should occur with one of the three drugs shown to reduce mortality: sustained-release metoprolol succinate (Toprol), carvedilol (Coreg), or bisoprolol (Zebeta; Class I, C) Beta-blockers should not be administered to patients with ACS with a recent history of methamphetamine or cocaine use who demonstrate signs of acute intoxication due to the risk of coronary spasm (Class III, C) |

4. High-intensity statin at discharge (titrated by age, side effects, and diagnosis) | To reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: For those patients 75 years or younger who have clinical atherosclerotic disease (even with an MI) with a high-intensity statin (Class I, A) For those over the age of 75 who have contraindications to high-dose statins, a moderate-dose statin should be recommended (Class IIA, B) |

5. Evaluation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) | STEMI: LVEF should be measured in all patients with STEMI (Class I, C) NSTEMI: A noninvasive imaging test is recommended to evaluate left ventricular function in patients with definite ACS (Class I, C) |

6. ACEI or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) at discharge | STEMI: An ACEI should be administered within the first 24 hours to all patients with STEMI with anterior location, HF, or LVEF less than 0.40, unless contraindicated (Class I, A) An ARB should be given to patients with STEMI who have indications for use but who are intolerant of ACEIs (Class I, B) NSTEMI: ACEIs should be started and continued indefinitely in all patients with LVEF below 0.40 and those with hypertension, stable chronic kidney disease, and DM unless contraindicated (Class I, A) ARBs are recommended for patients with HF or AMI with LVEF below 0.40 who cannot take an ACEI (Class I, A) |

7. Door-to-needle time | STEMI: In the absence of contraindications, fibrinolytic therapy should be administered to patients with STEMI at non-PCI-capable hospitals when the anticipated arrival-to-device time at a PCI-capable hospital exceeds 120 minutes because of unavoidable delays (Class I, B) When fibrinolytic therapy is indicated or chosen as the primary reperfusion strategy, it should be administered within 30 minutes of hospital arrival (Class I, B) In the absence of contraindications, fibrinolytic therapy should be given to patients with STEMI and onset of ischemic symptoms within the previous 12 hours when it is anticipated that primary PCI cannot be performed within 120 minutes of entry to the hospital (Class I, A) Fibrinolytic therapy should not be administered to patients with ST depression except when a true posterior MI is suspected or associated with ST elevation in lead aVR (Class III, B) In the absence of contraindications, fibrinolytic therapy should be administered to patients with STEMI and cardiogenic shock who are unsuitable candidates for either PCI or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) (Class I, B) |

8. First medical contact to device time | Primary PCI is the recommended method of reperfusion when it can be done promptly (Class I, A) EMS transport directly to a PCI-capable hospital for primary PCI is the recommended triage strategy for patients with STEMI, with an ideal door-to-device time system goal of 90 minutes or less (Class 1, B) Primary PCI should be performed for patients with STEMI and ischemic symptoms of 12 hours or less duration (Class I, A) |

9. Reperfusion therapy | Reperfusion therapy should be administered to all eligible patients with STEMI with symptom onset within the preceding 12 hours (Class I, A) In the absence of contraindications, fibrinolytic therapy should be administered to patients with STEMI at non-PCI-capable hospitals when the anticipated door-to-device time at a PCI-capable hospital exceeds 120 minutes because of unavoidable delays (Class I, B) In the absence of contraindications, fibrinolytic therapy should be given to patients with STEMI and onset of ischemic symptoms within the previous 12 hours when it is anticipated that primary PCI cannot be performed within 120 minutes of entry into the hospital (Class I, A) |

10. Door-in/door-out time | STEMI: Immediate transfer to a PCI-capable hospital for primary PCI is the recommended triage strategy for patients with STEMI who initially arrive at or who are transported to a non-PCI-capable hospital, with a first medical contact (FMC)-to-device time system goal of 120 minutes or less (Class I, B)

|

| Immediate transfer to a PCI-capable hospital for primary PCI is the recommended triage goal for patients with STEMI who initially arrive at or are transported to a non-PCI-capable hospital, with a door-to-device time system goal of 120 minutes or less (Class I, B) |

12. Cardiac rehab referral | For all CABG patients (Class I, B) STEMI patients (Class I, B) NSTEMI patients (Class I, B) Chronic angina (Class I, B) Disease prevention in female patients: ACS or risk for new-onset angina, stroke rehab (Class I, A) Recent percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) intervention (Class I, B) |

13. P2Y12 Inhibitor prescribed at discharge (e.g., clopidogrel [Plavix], prasugrel [Effient] or ticagrelor [Brilinta]) | STEMI: P2Y12 inhibitor therapy should be given for 1 year to patients with STEMI who receive a stent (bare-metal or drug-eluting) during primary PCI (Class I, B) NSTEMI: A P2Y12 inhibitor, in addition to aspirin, should be administered for up to 12 months to all patients with NSTE-ACS without contraindications who are treated with either an early invasive or ischemia-guided strategy (Class I B) |

(Jneid et al., 2017)

Table 5

Relief of Hypoxemia, Pain, and Anxiety per ESC Guidelines

Recommendations | Class | Level |

Oxygen is indicated for patients with hypoxemia (SaO2 less than 90% or PaO2 <60 mm Hg). | I | C |

Routine oxygen is not recommended for patients with an SaO2 above 90%. | III | A |

Pain relief with titrated opioids should be considered. | IIa | C |

A mild tranquilizer should be considered for very anxious patients. | IIa | C |

(Byrne et al., 2023)

Reperfusion Therapy

For patients with myocardial ischemia, reperfusion therapy should begin as soon as possible. If it can be completed within 12 hours of symptom onset and 120 minutes from diagnosis, primary PCI is the preferred reperfusion strategy for patients with STEMI. Primary PCI is performed with a balloon, stent, or other approved device on the infarct-related artery without previous fibrinolytic therapy. Preferably, this should be done in a STEMI-designated center. There is controversy regarding the time delay to primary PCI versus opting for more immediate treatment with fibrinolytic therapy. The ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guidelines highlight that PCI is superior to fibrinolytic therapy, but fibrinolytics can be used when a patient is in a non-PCI facility or when transfer to a PCI facility will be greater than 120 minutes. Both guidelines recommend that if the time from first medical contact to PCI device time is expected to be more than 120 minutes, fibrinolytic therapy should be used instead (unless contraindicated). Data are mixed, but the ESC recommends no more than 120 minutes from the STEMI diagnosis to PCI device time. The ideal time-lapse from first medical contact to PCI device time, per the ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI, is 90 minutes or less. Table 6 highlights the recommendations for reperfusion therapy according to ESC time goals. Table 7 discusses the difference in the ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI treatment guidelines for patients seen at PCI-capable facilities versus facilities that are not PCI-capable (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025).

The ESC makes a Class I recommendation for radial access (vs. femoral) during primary PCI as well as placement of a new-generation drug-eluting stent versus balloon angioplasty. The ESC guidelines recommend drug-eluting stents over bare-metal stents in all cases. Drug-eluting stents are preferred because they lower the risk of the artery renarrowing (restenosis), resulting in the need for repeat procedures. The ACC/AHA has previously cautioned against using these newer stents in patients with an increased risk of bleeding, an anticipated invasive or surgical procedure, or compliance struggles due to financial or social barriers. In these instances, a bare-metal stent may be used instead because they require a shorter duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). Still, most patients should receive drug-eluting stents. An anticoagulant during the procedure, as well as a P2Y12 (platelet) inhibitor, dosed before or at the time of primary PCI and continued for a year, is also a Class I recommendation of both guideline groups (Byrne et al., 2023; Jneid et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2025).

Unfractionated heparin should be given at a loading dose of 60 IU/kg and maintained for 48 hours or until PCI. Alternatively, 1 mg/kg of enoxaparin (Lovenox) can be given subcutaneously every 12 hours for the entire hospital stay or until PCI. Enoxaparin (Lovenox) has more efficient and predictable effects, yet a slightly higher risk of bleeding. Bivalirudin (Angiomax), a direct thrombin inhibitor with similar efficacy to heparin, is another option that may be used for PCI patients. For antiplatelet therapy, the ESC and ACC/AHA prefer ticagrelor (Brilinta) or prasugrel (Effient) over clopidogrel (Plavix) if available and indicated. The prognosis for right BBB and ischemia is poor. In these instances, emergent coronary angiography and PCI should be considered when persistent ischemic symptoms occur in the presence of a right BBB. PCI should be done promptly for patients with ongoing ischemic symptoms and atypical ECG findings suggestive of an isolated posterior AMI or left main coronary artery occlusion. Cardiac rupture is the most significant lethal complication of PCI. Although rare (less than 2%), this potential complication should be discussed with the patient and their family prior to the procedure and included on consent forms (Bikdeli et al., 2025; Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025b; Sweis & Jivan, 2024).

In NSTEMI patients, the ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI recommends an early (within 12–24 hours) invasive strategy, including diagnostic angiography with the intent to perform revascularization if indicated for stabilized patients with ACS without ST-segment elevation, if there is an elevated risk for clinical events based on the risk stratification score. This includes older patients, individuals assigned female at birth with elevated troponin, patients with a prior history of coronary bypass grafting, and patients presenting with HF, refractory angina, or hemodynamic or electrical instability. This is not recommended for patients with hepatic failure, renal failure, pulmonary failure, or cancer or for those with acute chest pain, a low likelihood of ACS, and normal troponin levels. If conservative treatment without PCI is elected, medical management (anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, beta-blockers, statins, and possible angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs]) is optimized, and noninvasive cardiovascular imaging is recommended (Rao et al., 2025; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025b; Sweis & Jivan, 2024).

Table 6

Recommendations for Reperfusion Therapy per the ESC

Recommendations | Class | Level |

Reperfusion therapy is indicated for patients with symptoms of ischemia of less than 12 hours in duration and persistent ST elevation. | I | A |

Primary PCI is recommended over fibrinolysis within indicated time frames (120 minutes from diagnosis per ESC, 120 minutes from first medical contact per ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI). | I | A |

If the patient is within 12 hours of symptom onset and timely primary PCI cannot be performed after STEMI diagnosis, fibrinolytic therapy is recommended within 10 minutes of diagnosis (per ESC) or 30 minutes of first medical contact (per ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI) without contraindications. | I | A |

For patients without ST-segment elevation, primary PCI is indicated with suspected active ischemic AMI symptoms and at least one of the following criteria:

| I | C |

Early angiography within 24 hours should be considered in patients with at least one of the following high-risk criteria:

| IIa | A |

A primary PCI strategy is recommended for patients with ongoing symptoms suggestive of ischemia, hemodynamic instability, or life-threatening arrhythmias and a time frame from symptom onset that is greater than 12 hours. | I | C |

Anticoagulation is recommended for all patients in addition to antiplatelet therapy and aspirin during primary PCI with unfractionated heparin (or bivalirudin [Angiomax] in cases of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia). | I | C |

Routine use of anticoagulation is recommended for all patients with ACS at the time of diagnosis. | I | A |

Fondaparinux (Arixtra) is not recommended for primary PCI in patients with a STEMI. | III | B |

For asymptomatic patients, a routine PCI is not recommended in patients with a STEMI presenting more than 48 hours after the onset of STEMI. | lll | A |

(Byrne et al., 2023)

Table 7

ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guidelines for the Management of Patients With STEMI

Facility Type | Recommendation |

Initially seen at a PCI hospital |

|

Initially seen at a non-PCI hospital |

|

(Rao et al., 2025)

A CABG may be indicated for patients with cardiogenic shock, high-risk anatomy, or cases of failed PCI or mechanical complications of PCI (discussed further on). It can also be considered for patients with left main disease if the patient’s anatomy is not favorable for PCI and their surgical risk is low. A CABG is a Class I recommendation from the ESC in cases of ongoing ischemia if PCI cannot be performed (Byrne et al., 2023; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025b; Sweis & Jivan, 2024).

Fibrinolytic Therapy

Guidelines indicate that fibrinolytic therapy should be administered as soon as possible to optimize effectiveness. If the fibrinolytic therapy is indicated, the goal per the ESC is to administer the bolus within 10 minutes of the diagnosis of STEMI, while the ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI recommendations advise administration within 30 minutes of hospital arrival (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025).

The ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guidelines recommend against administering fibrinolytic therapy to patients with ST-segment depression except when a true posterior AMI is suspected due to concurrent ST-segment elevation in the aVR lead. Despite mixed data on the topic, the clinical consensus is that fibrinolysis should not be attempted for STEMI patients with symptoms lasting longer than 12 hours when primary PCI is not feasible. The Class I recommendations from the ESC include the use of a fibrin-specific plasminogen activator such as tenecteplase (TNK-tPA, TNKase), alteplase (tPA, Activase), or reteplase (rPA, Retavase) in combination with aspirin and clopidogrel (Plavix). Enoxaparin (Lovenox) is also recommended as the anticoagulant of choice (vs. unfractionated heparin) until revascularization is performed or for at least 48 hours up to 8 days following an AMI. Caution should be used with enoxaparin (Lovenox) use for patients over 75 or those with renal impairment. Bivalirudin (Angiomax) may be used by those with a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Following administration, patients should be transferred immediately to a PCI-capable facility, with routine early PCI recommended 2–24 hours after administration. The ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guidelines define fibrinolysis as being unsuccessful if under 50% of the ST-segment alteration is not resolved within 60–90 minutes of fibrinolysis administration and recommend rescue PCI for these patients. The ESC recommends emergency angiography and PCI for patients who develop HF, cardiogenic shock, recurrent ischemia, or artery reocclusion (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025; Reeder & Kennedy, 2025b; Sweis & Jivan, 2024). Absolute contraindications to fibrinolysis include:

- any prior intracranial hemorrhage

- known structural cerebral vascular lesion

- known intracranial neoplasm (primary or metastatic)

- ischemic stroke within the past 3 months (except for acute stroke within 4.5 hours)

- suspected aortic dissection

- active bleeding or bleeding diathesis (excluding menses)

- significant closed-head or facial trauma within 3 months

- intracranial or intraspinal surgery within 2 months

- severe uncontrolled hypertension (unresponsive to emergency therapy; Gibson & Alexander, 2024; Sweis & Jivan, 2025b)

Relative contraindications include:

- history of chronic, severe, poorly controlled hypertension

- SBP above 180 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) above 110 mm Hg

- history of prior ischemic stroke more than 3 months ago

- dementia

- known intracranial pathology not covered in absolute contraindications

- traumatic or prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR, longer than 10 minutes)

- recent (within 2–4 weeks) internal bleeding

- noncompressible vascular punctures

- pregnancy

- active peptic ulcer disease

- current use of anticoagulants: the higher the international normalized ratio (INR), the higher the risk of bleeding (Gibson & Alexander, 2024; Sweis & Jivan, 2025b)

Cerebral hemorrhage is the most lethal complication of fibrinolytic therapy. It is more common in patients with older age, lower weight, prior cerebrovascular disease, hypertension on admission, and those assigned female at birth (Gibson & Alexander, 2024; Sweis & Jivan, 2025b).

Treatment Time Targets

Specific time targets are necessary to set guideline suggestions for prompt treatment. Many studies by various national and international groups have come to a consensus on time frames. Refer to Table 8 for a listing of those targets.

Table 8

Treatment Time Targets per the ESC

Milestone | Time Target |

First medical contact to ECG and subsequent diagnosis | Less than 10 minutes |

Expected delay from STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI (wire crossing) to choose primary PCI in lieu of fibrinolysis | Less than 120 minutes |

Time from STEMI diagnosis to wire crossing in patients who present at primary PCI hospitals | Less than 60 minutes |

Time from STEMI diagnosis to wire crossing in transferred patients | Less than 90 minutes |

Time from STEMI diagnosis to bolus or infusion start of fibrinolysis in patients unable to meet primary PCI times | Less than 10 minutes |

The time delay from the start of fibrinolysis to the evaluation of its effectiveness | 60–90 minutes |

The time delay from the start of fibrinolysis to angiography (if fibrinolysis is successful) | 2–24 hours |

(Byrne et al., 2023)

Assessment and Monitoring

Healthcare providers (HCPs) must respond rapidly and efficiently to patients who are experiencing symptoms of an AMI to assess their circulation, airway, and breathing. In addition, they must work quickly to assess the level of consciousness; administer sublingual nitroglycerin (Nitrostat, NitroMist, NTG) and aspirin, if indicated; and obtain a 12-lead ECG. The incidence of sudden death is high during the first hour of an AMI, so the health care team must monitor the patient closely and be prepared for an emergency (Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Reeder & Mahler, 2025; Urden et al., 2021).

One of the most crucial assessments when caring for a patient with a suspected AMI is a pain assessment. Chest pain can occur secondary to pulmonary edema, congestive HF, pericarditis, pneumothorax, and unstable angina. A systematic method for assessing chest pain should be utilized, including precipitating factors, quality, duration, location, and radiation. MI-associated chest pain is often precipitated by activity but does not resolve with rest, is typically intense, and may be described as pressure or burning (Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Reeder & Mahler, 2025; Urden et al., 2021). It often begins substernally in the center of the chest and radiates to the left arm, neck, jaw, shoulder, or back. If a patient is stable, the HCP should perform a focused assessment, including the following:

- Review of the presenting symptoms/illness

- Overview of general cardiac history (previous diagnoses, surgeries, interventions, diagnostic studies, medications/herbs/vitamins)

- Family history, specifically of CAD, hypertension, peripheral artery disease, stroke, or DM

- Survey of lifestyle risk factors for CAD (sedentary lifestyle, a diet high in sodium and saturated fats; Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Reeder & Mahler, 2025; Urden et al., 2021)

The patient’s vital signs should be monitored closely, with a target SBP range of 100–140 mm Hg. All patients should be placed on continuous cardiac monitoring after the initial 12-lead ECG using a 3- or 5-lead system to monitor for indications of worsening or developing ischemia (Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Reeder & Mahler, 2025; Urden et al., 2021).

When a patient experiences an AMI, HCPs focus most of their attention on meeting the imminent physical needs of the patient; however, an AMI is an extremely stressful experience for the patient and their family. Emotional stress can have a profound effect on physiologic functions. During times of anxiety and apprehension, the sympathetic nervous system is activated. As a result, heart rate and cardiac contractility increase, blood vessels constrict, and cardiac output initially increases. These responses, in turn, boost the myocardial oxygen demand in a compromised patient. As the heart demands more oxygen and the supply diminishes, the patient may experience more chest pain and other signs of hemodynamic instability. These changes may aggravate the patient’s fear and anxiety. The health care team should attempt to make the environment less stressful. If possible, schedule laboratory tests, ECGs, imaging, and other diagnostic tests for completion within the same time frame. Rest is an essential part of the recovery process, and allowing for uninterrupted rest periods and sleep is helpful (Ojha & Dhamoon, 2023; Reeder & Mahler, 2025; Urden et al., 2021).

Complications Associated with AMI

Cardiac Arrest/Ventricular Fibrillation

Many deaths occur early after a STEMI outside of the hospital setting. The primary lethal arrhythmia that occurs is ventricular fibrillation (VF). VF results in an ineffective quivering of the ventricles and no cardiac output. Treatment includes airway, breathing, circulation, defibrillation, and other advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) interventions. The sooner the VF is treated, the greater the chance of patient survival will be. All medical and paramedical personnel caring for patients with suspected AMI outside the hospital should have access to defibrillation equipment and training in cardiac life support. Continuous cardiac monitoring should be implemented for all patients admitted to the hospital with known or suspected AMI after completing the initial 12-lead ECG (Byrne et al., 2023; Elmer & Coppler, 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a).

As a result of the high prevalence of coronary occlusions and the potential difficulties of interpreting ECG findings for patients after cardiac arrest, urgent angiography within 2 hours of cardiac arrest should be considered for survivors, including unresponsive survivors. A high index of suspicion of ongoing infarction is indicated by the presence of chest pain before the arrest, a history of established CAD, and abnormal or uncertain ECG results. Unconscious patients admitted to critical care units after out-of-hospital cardiac arrests are at high risk for death, and neurologic deficits are common among those who survive. ESC recommendations for cardiac arrest are listed in Table 9 and include guidelines for PCI, temperature control, and medical management in patients post cardiac arrest. The ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI recommends immediate angiography (and PCI if indicated) for patients who are resuscitated after an out-of-hospital arrest if the ECG shows STEMI, as well as initiating therapeutic hypothermia (i.e., cooling the body to a temperature below normal to preserve brain function) as soon as possible for comatose patients with a history of VF or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT; Byrne et al., 2023; Elmer & Coppler, 2025; Rao et al., 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a).

Table 9

Recommendations for Cardiac Arrest per the ESC

Recommendations | Class | Level |

Primary PCI for patients with resuscitated cardiac arrest and STEMI on the ECG | I | B |

Targeted temperature management is indicated early for those who remain unresponsive following resuscitation. | I | B |

Systems should facilitate the transfer of patients with suspected AMI so they have access to PCI services 24/7 via specialized EMS. | I | C |

Evaluation of neurologic prognosis is recommended in all comatose survivors after cardiac arrest (no earlier than 72 hours after admission). | I | C |

Transport of patients with an out-of-hospital arrest to a cardiac care center should be considered. | I | C |

Routine immediate angiography after cardiac arrest is not recommended in patients who are hemodynamically stable without persistent ST-segment elevation. | III | A |

(Byrne et al., 2023)

Following an AMI, prompt revascularization is recommended to correct any myocardial ischemia, as this is commonly the underlying cause of recurrent VF. Electrolyte imbalances (especially hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia) should be corrected. An IV beta-blocker is recommended for polymorphic VF. Radiofrequency catheter ablation should also be considered for recurrent VF. Long-term, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is recommended for patients who are at least 6 weeks after their AMI with symptomatic HF (NYHA Class II-III) and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of less than 35% despite optimal medical therapy for at least 3 months. In certain high-risk patients within 40 days of their AMI, an implantable or wearable cardioverter-defibrillator may be considered (Byrne et al., 2023; Elmer & Coppler, 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a).

Coronary Artery Reocclusion

A few patients will experience reocclusion of the artery after fibrinolytic therapy, even when preventive measures are taken. While the clot in the artery has been dissolved, the atherosclerotic plaque is still present; if anticoagulation is inadequate, another thrombus may form. Symptoms can include chest pain, nausea, diaphoresis, and ST-segment elevation, similar to those experienced with the original episode. With this in mind, monitoring each patient closely and being aware of changes indicative of reocclusion is imperative. Repeat administration of a fibrinolytic agent is not recommended. The ESC advises emergency angiography and PCI (if indicated) for these patients (Class I/Level B). To prevent this emergency, ESC guidelines recommend transfer to a PCI-capable facility after fibrinolysis for routine early angiography with subsequent PCI if indicated 2–24 hours after fibrinolytic administration (Byrne et al., 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Urden et al., 2021).

HF and Cardiogenic Shock

Congestive HF following an AMI can range from mild to severe, depending on the extent of ventricular damage. HF occurs due to myocardial tissue damage and the subsequent decrease in the efficiency of the ventricle(s) as a pump. In right-sided HF, the compromised right ventricle causes fluid to back into the peripheral circulation. In left-sided HF, fluid backs into the pulmonary circulation. Signs of HF include shortness of breath; hypoxia; production of pink, frothy sputum; hypotension; oliguria; confusion or changing level of consciousness; and tachycardia. HF as a result of an AMI increases the risk of other complications, such as respiratory failure, worsening renal function, pneumonia, and death. New-onset HF should be distinguished from preexisting HF. These patients should undergo emergent echocardiography or chest ultrasound to gather information about right and left ventricular function (Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Urden et al., 2021).

Treatment of HF depends primarily on the severity. Typical management includes supplemental oxygen (if pulmonary edema is present and SaO2 is below 90%). The ESC recommends starting an ACEI and beta-blocker as soon as the patient is hemodynamically stable, as well as a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) in those with an LVEF under 40% and no significant renal failure or hyperkalemia. For patients with symptoms of fluid overload, a loop diuretic is recommended. If the patient’s SBP is above 90 mm Hg, nitrates are recommended. Morphine (MS Contin) or a similar opiate to relieve dyspnea and anxiety, and/or inotropic agents to improve cardiac contractility, may be considered for these patients if needed. They will be quite ill and may require transfer to the critical care unit. Mechanical ventilation and intubation may also be necessary if the patient develops hypoxemia or hypercapnia and becomes acidotic and/or exhausted, although noninvasive ventilation should be attempted first (Byrne et al., 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Urden et al., 2021).

As previously mentioned, right ventricular infarcts can be complicated to manage. An echocardiogram may be required to confirm the presence of a right ventricular infarct. These patients often present with symptoms of right-sided HF (i.e., jugular venous distension/pulsation, hypotension, right-sided S3, and Kussmaul sign). Treatment will involve careful volume/fluid maintenance and may require dobutamine (Dobutrex, an inotropic pressor) or an intra-aortic balloon pump. A pulmonary artery catheter may be useful during monitoring, and nitrates or other medications that reduce preload should be avoided for these patients (Byrne et al., 2023; Levin & Goldstein, 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a).

Patients with HF can rapidly decline into cardiogenic shock. Cardiogenic shock occurs when the infarction affects 40% or more of the myocardium. Since the heart cannot contract with sufficient force, the vital organs and peripheral tissues cease to function due to ischemia. The patient may experience pulmonary congestion, diaphoresis, cool extremities, and confusion. Treatment for cardiogenic shock is aggressive and can include fluid replacement or diuresis/ultrafiltration, inotropic/vasopressor agents, and an intra-aortic balloon pump in the case of mechanical complications; this is an invasive device used to decrease ventricular workload and improve coronary artery perfusion (Byrne et al., 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Urden et al., 2021).

Monitoring for these patients should include invasive blood pressure monitoring (arterial line) and blood gas assessment to determine whether respiratory support is required; hemodynamic monitoring with a pulmonary artery catheter may be considered. Doppler echocardiography should be done to rule out mechanical complications as well as to assess ventricular/valvular function and loading conditions. If found, mechanical complications should be treated as quickly as possible (i.e., intra-aortic balloon pump). The ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI and ESC make a Class I recommendation for primary PCI therapy for patients with STEMI and cardiogenic shock or acute severe HF, regardless of a delay from symptom onset, if the anatomy is suitable. CABG is recommended for those with unsuitable anatomy or in the case of failed PCI. The ESC specifies in a Class II recommendation that complete revascularization should be considered during the index procedure for patients with cardiogenic shock. Fibrinolytic therapy is recommended for those who are unsuitable for either CABG or PCI. After fibrinolysis, these patients should be transferred immediately to a PCI-capable hospital for coronary angiography, irrespective of time delay. Unfortunately, death occurs in about 85% of patients who develop cardiogenic shock. Therefore, nursing interventions should include assisting patients and families in working through end-of-life issues (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Urden et al., 2021).

Arrhythmias

Successful thrombolysis can cause a variety of cardiac arrhythmias, such as AF, VT, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), accelerated idioventricular rhythm, and sinus bradycardia. Of all AMI patients, 90% develop an arrhythmia, with 25% occurring in the first 24 hours. Most are self-limited and benign. The risk of VF and other serious arrhythmias is greatest in the first hour. These are generally accepted as expected consequences of coronary reperfusion, and treatment is unnecessary unless a patient becomes unstable. The use of antiarrhythmic medications for STEMI patients is difficult, as their evidence for benefit is limited, and they have been shown to increase the risk of early mortality. Prompt revascularization is recommended to correct any myocardial ischemia, as this is commonly the underlying cause (Byrne et al., 2023; Spragg & Kumar, 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Urden et al., 2021).

AF

Up to 21% of STEMI patients are affected by either new-onset or preexisting (known or unknown) AF. If stable, no treatment other than anticoagulation may be necessary. Long-term anticoagulation is based on the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Rate control can be achieved with the use of IV beta-blockers (if no acute HF or hypotension) or IV digoxin (Lanoxin, if acute HF and hypotension are present), rhythm control with amiodarone (Pacerone, Cordarone, if acute HF is present without hypotension). The use of ACEIs or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and statin therapy may also reduce the rate of new-onset AF after AMI. If a patient is unstable, cardioversion may be considered if adequate rate control is not achieved with pharmacologic agents and in the presence of ongoing ischemia, hemodynamic compromise, or HF, but there is frequent early recurrence. IV amiodarone (Pacerone, Cordarone) can also promote electrical cardioversion or decrease the risk of early recurrence after cardioversion. Digoxin (Lanoxin) is not recommended for converting AF to sinus rhythm or rhythm control; calcium channel blockers and beta-blockers are also not recommended for converting AF to sinus rhythm (Byrne et al., 2023; Spragg & Kumar, 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a).

VT

Patients who have suffered an AMI may experience VT. This ventricular arrhythmia can be benign or life-threatening. Patients may be asymptomatic or may experience shortness of breath, chest discomfort, palpitations, and syncope. Prompt revascularization is recommended to correct any myocardial ischemia, as this is commonly the underlying cause of recurrent VT. Electrolyte imbalances (especially hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia) should be corrected. IV beta-blockers and/or amiodarone (Pacerone, Cordarone) are recommended for polymorphic VT. If a patient is unstable, electrical cardioversion may be conducted in an attempt to convert the myocardium to sinus rhythm. This arrhythmia is most common in patients who have experienced an anterior or anterolateral AMI. IV amiodarone (Pacreone, Cordarone) may also be used for recurrent VT if repeated cardioversion is unsuccessful. Patients may be given lidocaine (Xylocaine) if amiodarone (Pacerone, Cordarone) is contraindicated or to manage recurrent VT not responding to cardioversion, beta-blockers, amiodarone (Pacerone, Cordarone), and overdrive stimulation. Transvenous catheter pace termination or overdrive pacing should be considered if cardioversion is unsuccessful. Radiofrequency catheter ablation should also be considered for recurrent VT or VF. Long-term, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is recommended for patients who are at least 6 weeks post AMI with symptomatic HF (NYHA Class II-III) and an LVEF of less than 35% despite optimal medical therapy for at least 3 months. For certain high-risk patients, an implantable or wearable cardioverter-defibrillator may be considered for those within 40 days of an AMI (Byrne et al., 2023; Podrid & Tzou, 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Urden et al., 2021).

Sinus Bradycardia and High-Degree Atrioventricular Block

Bradycardia is a slowing of the heart rhythm. Heart blocks occur as a result of problems in the atrioventricular (AV) node of the conduction system. Electrical impulses are not conducted from the atrium to the ventricles, which can decrease cardiac output. Second-degree AV blocks are more common with inferior wall AMIs. These patients may experience hypotension and syncope. If a patient is symptomatic, IV epinephrine (Adrenalin), vasopressin (Vasostrict), or atropine (AtroPen) is recommended (Class I) by the ESC. To correct the arrhythmia, patients may need transcutaneous (external) pacing or surgery to implant a pacemaker. Implantation of a permanent pacemaker is recommended when an AV block does not resolve within 5 days after an AMI. Angiography with the potential for revascularization is recommended if reperfusion therapy has not already been done (Byrne et al., 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Urden et al., 2021).

Mechanical Complications

Although rare, mechanical complications from AMI can be lethal and may occur in the first few days following STEMI. Primary PCI has reduced the rate of these complications, but HCPs must be aware and watchful for indications of mechanical complications. Patients may present with sudden-onset hypotension, recurrence of chest pain, pulmonary congestion, a new murmur (which indicates mitral regurgitation or ventricular septal defect), or jugular venous distension. If these symptoms develop, an immediate echocardiogram is warranted to rule out a mechanical complication such as free wall rupture, ventricular septal rupture, papillary muscle rupture, or aneurysm/pseudoaneurysm. Surgical repair (CABG) may be required. Aneurysms are also a potential complication of AMI. Individuals assigned female at birth are more prone to an aneurysm, as well as patients with single-vessel disease, total occlusion of the left anterior descending artery, and those with no previous history of angina. Left ventricular aneurysms may present with signs and symptoms of HF, ventricular arrhythmias, or recurrent embolization (Byrne et al., 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a; Thiele & Abbott, 2025).

Pericarditis

HCPs should also be watchful for pericarditis (early [from a few hours to 4 days] or late [1–2 weeks after AMI]) or pericardial effusion following an AMI, as these are also potential complications. Incidence has decreased with the use of PCI and thrombolysis but remains roughly 10%, typically developing within the first 24–96 hours. This is due to inflammation of the pericardial tissue adjacent to the infarcted myocardium. Symptoms may include pleuritic chest pain and an audible pericardial friction rub. The ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI recommends acetaminophen (Tylenol) for symptomatic relief for early pericarditis that will usually resolve with conservative therapy. For early pericarditis with persistent symptoms or late pericarditis, high-dose aspirin (ASA) may be used to reduce symptoms. They also recommend against using corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for treating pericarditis following AMIs secondary to increased risk of major adverse events (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a).

Left Ventricular Mural Thrombus

In 20–40% of post-AMI patients (and up to 60% of anterior AMI patients treated with anticoagulants), a left ventricular mural thrombus (blood clot on the wall of the left ventricle) can lead to systemic embolization. Anticoagulant therapy decreases the risk of this complication and is recommended (Byrne et al., 2023; Sweis & Jivan, 2025a).

Post-AMI Care

The ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI and ESC guidelines contain information regarding the care of patients following an AMI. All AMI patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) under 75 should be placed on a high-intensity statin indefinitely if they can tolerate it. This treatment may include atorvastatin (Lipitor) at 40 or 80 mg daily or rosuvastatin (Crestor) at 20 or 40 mg daily. A moderate-intensity statin may be used if the patient cannot tolerate the higher-intensity dose. Treatment in patients over the age of 75 should be considered based on individual risks and benefits (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025; Rosenson & Lopez-Sendon, 2025). The ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI and ESC make the following suggestions regarding ongoing care and secondary prevention in STEMI patients (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025; Rosenson & Lopez-Sendon, 2025):

- LVEF should be assessed for all STEMI patients prior to discharge.

- Noninvasive stress testing is recommended before discharge for all STEMI patients who did not undergo angiography and who are not considered high risk.

- Daily aspirin should be prescribed indefinitely to all patients after AMI, after successful PCI.

- Daily aspirin should be prescribed indefinitely after successful fibrinolysis, along with clopidogrel (Plavix) at 75 mg daily (DAPT) for at least 2 weeks and up to 1 year.

- A beta-blocker should be prescribed during and after hospitalization if not contraindicated (e.g., first-degree heart block with a PR interval over 240 ms, second- or third-degree heart block without a cardiac pacemaker, severe/advanced reactive airway disease, or recent cocaine use). Preferably, metoprolol (Toprol), carvedilol (Coreg), or bisoprolol (Zebeta) should be used, as these have been shown to reduce the mortality risk among patients with HF.

- An ACEI should be started within 24 hours for all STEMI patients with an anterior AMI, HF, or LVEF below 40%. An ARB may be given if the patient is intolerant.

- DAPT with a P2Y12 inhibitor, such as clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient), or ticagrelor (Brilinta), should be prescribed for 1 year to all patients with a stent placed during PCI unless contraindicated.

Recommendations for NSTEMI patients include the following (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025; Rosenson & Lopez-Sendon, 2025):

- Noninvasive imaging is advised to evaluate LVEF in all NSTEMI patients before discharge.

- Noninvasive stress testing is recommended prior to discharge for low- to intermediate-risk NSTEMI patients free of ischemia.

- Daily aspirin should be prescribed to all AMI patients indefinitely after successful PCI.

- Beta-blocker therapy is needed for NSTEMI patients with stabilized HF and reduced systolic function if not contraindicated (refer to previous). Preferably, metoprolol (Toprol), carvedilol (Coreg), or bisoprolol (Zebeta) should be used, as they have been shown to reduce the mortality risk among patients with HF.

- An ACEI should be continued indefinitely for NSTEMI patients with an LVEF below 40%, hypertension, DM, and chronic kidney disease. An ARB is recommended for those with HF or ACEI intolerance.

- DAPT with a P2Y12 inhibitor—such as clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient), or ticagrelor (Brilinta)—should be prescribed for 1 year to all patients with NSTE-ACS without contraindications who are treated with either an early invasive or ischemia-guided strategy.

Refer to Table 4 for additional details regarding ACC/AHA performance measures for STEMI/NSTEMI patients.

In 2004, the ACC/AHA published a Class I recommendation for the prescription of formal cardiac rehabilitation for all patients with recent ACS or NSTEMI, recent revascularization, unstable angina, post-CABG status, or HF with reduced LVEF. Aerobic training within cardiac rehabilitation should be included, with 30 minutes of exercise at a frequency of three or more times per week. Lifestyle modifications—including adopting a low-fat and low-salt diet, smoking cessation, maintaining vaccinations, and increasing physical activity—have all been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent AMI (Byrne et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2025; Rosenson & Lopez-Sendon, 2025; Sweis & Jivan, 2024). In 2019, the ACC/AHA published the following ten key messages regarding the primary prevention of CVD, which may be useful for patient discharge planning and education (Arnett et al., 2019):

- A healthy lifestyle over a lifetime is the most important way to prevent atherosclerotic vascular disease, HF, and AF.

- A team-based care approach is an effective strategy for CVD prevention. To inform treatment decisions, HCPs should evaluate the social determinants of health that affect individuals.

- Adults aged 40–75 years being evaluated for CVD prevention should undergo a 10-year atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk estimation and have a clinician-patient risk discussion before starting pharmacotherapy (e.g., antihypertensive therapy, statin, or aspirin). The presence or absence of additional risk factors and/or the use of coronary artery calcium (CAC) scanning can help guide decisions about preventive interventions for select individuals.

- All adults should consume a healthy diet that emphasizes the consumption of vegetables, fruits, nuts, whole grains, lean vegetable or animal protein, and fish and minimizes the intake of trans fats, red and processed meats, refined carbohydrates, and sweetened beverages. For patients with an elevated BMI, counseling and caloric restriction are recommended to achieve and maintain weight loss.

- Adults, including those with DM, should engage in at least 150 minutes per week of accumulated moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity physical activity.

- For adults with DM, lifestyle changes (e.g., improving dietary habits and achieving exercise recommendations) are crucial. If medication is indicated, metformin (Glucopage) is first-line therapy, followed by consideration of a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2) or a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1).

- At every health care visit, assess all adults for tobacco use. Assist tobacco users and strongly advise them to quit.

- Aspirin should be used infrequently in the routine primary prevention of ASCVD because of a lack of net benefit.

- Statin therapy is the first-line treatment for the primary prevention of ASCVD in patients with elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels (above 190 mg/dL), those with DM who are aged 40–75 years, and those determined to be at sufficient ASCVD risk after a clinician-patient risk discussion.

- Nonpharmacologic interventions are recommended for all adults with elevated blood pressure or hypertension. When pharmacologic therapy is required, the target blood pressure is below 130/80 mm Hg.

Patient and Family Education/Support

HCPs play an important role in educating patients and families. Initial information should be simple and concise and focus on what to expect. Educating each patient and their family about thrombolytic agents and PCI may also be necessary to make informed decisions. HCPs must remember to use layperson terms when describing medications and procedures. For example, HCPs may want to describe the thrombolytic agent as a medicine used to dissolve clots in the arteries of the heart. Most importantly, HCPs should offer emotional support and attempt to relieve patient anxiety. It is appropriate in most cases to begin more detailed education once the patient’s condition has stabilized and their fear and anxiety have subsided. Also, consider using pictures and diagrams of the heart and providing educational information that the patient can take home and review later (Urden et al., 2021).

HCPs should consider each patient’s learning style, learning challenges, and preferred language. Give information in a way that will be most beneficial to the patient. For example, provide written materials in the patient’s native language and use a translation service or professional translator if needed. To address individual learning needs, offer the patient multiple choices, such as a booklet or a 15-minute video. Always remain open to queries, and emphasize to the patient and their family that their questions are important. The next step in the patient education process usually occurs once a patient transfers from an intensive care unit to a monitored floor or intermediate care area. Patients and families may be less anxious at this point and begin making discharge plans. Patients may also begin to ask questions about lifestyle changes. Remember that each individual may have different ideas about what caused their AMI. One patient may attribute it to smoking, while another may think it was brought on by workplace stress. The HCP should discuss the patient’s perceptions and talk about making lifestyle changes specific to these perceptions, keeping in mind that patients will usually have greater motivation to change the things that are most meaningful to them (Urden et al., 2021).

Discharge teaching is an essential part of post-AMI care and helps prevent readmissions. The HCP should give the patient verbal and written instructions about medications, smoking cessation, exercise, daily activities, returning to work, and dietary changes. Most patients will also be discharged with prescriptions, including anticoagulants, beta-blockers, ACEIs, and a lipid-lowering drug. It is helpful to provide verbal and written instructions about the medications. It is also valuable to assess whether the patient has the necessary resources to acquire medications. If not, a social worker or case manager may be able to assist the patient. The patient and their family should also be given specific instructions for any recurring chest pain (Urden et al., 2021).

References

ACLS.com. (n.d.). THROMBINS2 is the new MONA. Retrieved November 30, 2025, from https://acls.com/articles/thrombins-is-new-mona

American Heart Association. (2024). About arrhythmia. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/arrhythmia/about-arrhythmia