About this course:

This learning activity reviews the anatomy and physiology of the breast and addresses the prevalence, recommendations, benefits, contraindications, and complications of breastfeeding. It outlines proper infant positioning on the breast, care of breastfeeding patients, and promotion of breastfeeding in the hospital setting.

Course preview

Breastfeeding Education

This learning activity reviews the anatomy and physiology of the breast and addresses the prevalence, recommendations, benefits, contraindications, and complications of breastfeeding. It outlines proper infant positioning on the breast, care of breastfeeding patients, and promotion of breastfeeding in the hospital setting.

By completing this activity, learners will be able to:

- review anatomic and physiological aspects of breastfeeding

- describe current recommendations for infant feeding

- discuss the benefits of breastfeeding for infants, parents, families, and society

- analyze common problems associated with breastfeeding and interventions to resolve them

- explain maternal and infant indicators of effective feeding

- note the implications for nursing care and future research on breastfeeding

Anatomy and Physiology

Adult breasts appear on the ventral aspect of the thorax, extending from the second to sixth or seventh intercostal space. Breasts begin to develop in utero, and a rudimentary mammary ductal system is present at birth. After birth, areola and nipple growth mimic the growth of other body tissues. This is as far as breast tissue progresses in persons assigned male at birth. During puberty, insulinlike growth factor and estrogen stimulate mammary growth in persons assigned female at birth. This breast development (thelarche) is usually the first indication in a person assigned female at birth that puberty is beginning. Complete maturation and differentiation of the tissue continue for the next 4 years. Many hormones influence breast development, such as progesterone, estrogen, prolactin, growth hormone, thyroid and parathyroid hormones, insulin, and cortisol (Rogers & Brashers, 2023).

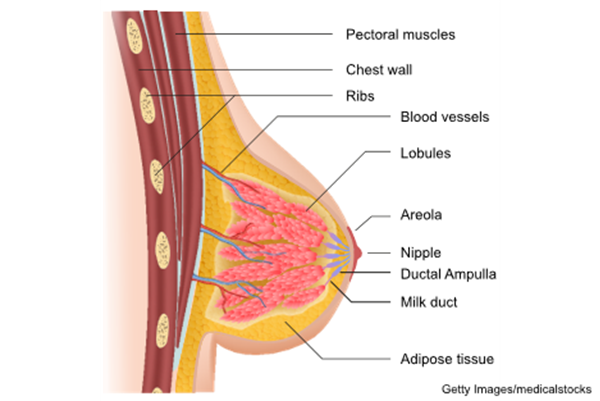

A fully developed breast in a person assigned female at birth has 15 to 20 pyramid-shaped lobes supported by ligaments of Cooper. Each lobe consists of 20 to 40 lobules subdivided into functional units known as acini (also called alveoli). The acini are lined with epithelial cells that can secrete milk and myoepithelial cells that can squeeze the milk out of the acini. The acini empty into lobular collecting ducts, which open into the interlobular collection and ejecting ducts. These ducts reach the skin through pores in the nipple (refer to Figure 1; Rivard et al., 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023).

Figure 1

Lobules and Ducts of the Breast

During pregnancy, the breasts undergo significant remodeling into milk-secreting organs due to the stimulatory effects of estrogen, progesterone, and placental lactogen on the growth of glandular and disappearance of adipose tissues. The glandular tissue increases and takes over while the adipose tissue almost disappears in a lactating breast. Blood flow to the breast nearly doubles, causing the veins in lactating breasts to become more prominent. The nipples and areolas enlarge, along with glands of Montgomery on the areola. Glands of Montgomery are sebaceous glands that produce an oily substance to protect against infection and mechanical stress caused by the infant's sucking (Colleluori et al., 2021; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Shah et al., 2022).

Stages of Human Breast Milk Production

Lactogenesis, the process of developing the ability to produce and secrete human breast milk (HBM), is divided into two stages. Stage 1 (secretory initiation) occurs during the second half of pregnancy. In this stage, the placenta releases high levels of progesterone, stimulating the breasts to prepare for HBM production by producing colostrum (prepartum milk). By late pregnancy, some patients can hand-express colostrum from their breasts. Stage 2 (secretory activation) begins once the placenta is removed after delivery, initiating a rapid drop in progesterone levels and a rise in prolactin, cortisol, and insulin. For the first 2 to 3 days following delivery, the lactating breasts produce colostrum, which is essential for the newborn infant’s digestive tract to bind bilirubin, pass meconium, and establish normal Lactobacillus bifidus. Colostrum slowly changes to transitional milk, and by 3 to 5 days postpartum, most patients experience swelling or engorgement due to the volume of HBM produced. Mature milk is established about 10 days postpartum (Pillay & Davis, 2023).

Lactation

Prolactin and oxytocin are the two hormones that play essential roles in successful lactation. The anterior pituitary gland secretes prolactin in response to nipple stimulation. Its release is inhibited by dopamine from the hypothalamus. Prolactin promotes the growth of mammary gland ducts, encourages the proliferation of epithelial cells, and triggers the synthesis of milk proteins. Oxytocin is vital in the let-down reflex. The posterior pituitary gland releases oxytocin to adjacent capillaries, traveling to the mammary myoepithelial cell receptors to stimulate cell contraction when the infant starts to suckle at the breast. The myoepithelial cells that line the ducts of the breast contract when stimulated and expel HBM from the alveoli into the ducts that empty through the nipple. Catecholamine production (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine/noradrenaline, and epinephrine/adrenaline) due to pain or stress may inhibit this process (Kalarikkal & Pfleghaar, 2023; Pillay & Davis, 2023; Ziomkiewicz et al., 2021).

HBM Composition

HBM is the ideal food for infants. Each individual's HBM composition is unique and changes based on their nutritional intake and the infant's specific nutritional and immunological needs. HBM contains immunoglobulins that protect infants against pathogens. It is also composed of macronutrients, vitamins, minerals, hormones, and growth factors (Kim & Yi, 2020; Shah et al., 2022).

Macronutrients

HBM is composed of 87% to 88% water and 124 g/L of macronutrients. Mature milk usually contains 65 to 70 cal per 100 mL of energy, with 50% of calories coming from fat and 40% from carbohydrates. The macronutrient levels within colostrum and mature milk are described in Table 1 (Kim & Yi, 2020).

Table 1

Macronutrient Composition of HBM

|

r-right: none; padding: 0in 5.4pt;"> Macronutrient | Colostrum | Mature Milk |

Carbohydrate | 50 to 62 g/L | 60 to 70 g/L |

Lactose | 20 to 30 g/L | 67 to 70 g/L |

Oligosaccharides | 20 to 24 g/L | 12 to 14 g/L |

Protein | 14 to 16 g/L | 8 to 10 g/L |

Fat | 15 to 20 g/L | 34 to 40 g/L |

(Kim & Yi, 2020)

Vitamins and Minerals

Although a lactating patient's diet can influence HBM components, it usually contains all the vitamins and minerals their infant needs to grow. The vitamins HBM lacks in sufficient amounts are vitamins D and K, and an exclusively breastfed infant may require supplementation. This is especially true in regard to vitamin D for infants born in climates without extended sun exposure. The mineral composition of HBM is described in Table 2. Maternal supplementation with 6,400 IU of vitamin D daily is an alternative backed by research but is only recommended if direct infant supplementation is not possible (CDC, 2025d; Heo et al., 2022; Kim & Yi, 2020).

Table 2

Mineral (Micronutrient) Composition of HBM

Micronutrient | Colostrum | Mature Milk |

Iron | 0.5 to 1 mg/L | 0.3 to 0.7 mg/L |

Calcium | 250 mg/L | 200 to 250 mg/L |

Phosphorus | 120 to 160 mg/L | 120 to 140 mg/L |

Magnesium | 30 to 35 mg/L | 30 to 35 mg/L |

Sodium | 300 to 400 mg/L | 150 to 250 mg/L |

Chloride | 600 to 800 mg/L | 400 to 450 mg/L |

Potassium | 600 to 700 mg/L | 400 to 550 mg/L |

Manganese | 5 to 12 mcg/L | 3 to 4 mcg/L |

Iodine | 40 to 50 mcg/L | 140 to 150 mcg/L |

Selenium | 25 to 32 mcg/L | 10 to 25 mcg/L |

Copper | 0.5 to 0.8 mcg/L | 0.1 to 0.3 mcg/L |

Zinc | 5 to 12 mcg/L | 1 to 3 mcg/L |

(Kim & Yi, 2020)

Hormones and Growth Factors

The functions and effects of hormones in HBM are not entirely understood. However, they serve as various bioactive proteins and peptides. Hormones in HBM include parathyroid hormone, insulin, leptin, ghrelin, apelin, nesfatin-1, obestatin, and adiponectin. In contrast, many growth factors have been studied extensively and are known to have various effects on the gastrointestinal system, vasculature, nervous system, and endocrine system. Growth factors and their function are detailed in Table 3 (Kim & Yi, 2020).

Table 3

Growth Factors in HBM and Their Functions

Growth Factors | Functions |

Epidermal growth factor | Maturation and healing of the intestinal tract |

Neuronal growth factor | Development of the enteric nervous system in newborns |

Insulinlike growth factor | Stimulation of erythropoiesis |

Vascular endothelial growth factor | Regulation of angiogenesis |

Erythropoietin | Increasing the number of red blood cells |

Adiponectin | Regulation of metabolism and suppression of inflammation |

(Kim & Yi, 2020)

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Multiple medical authorities including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and World Health Organization (WHO) recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of an infant’s life with continuation of breastfeeding until 2 years old or beyond in conjunction with complementary foods. Despite these recommendations, the WHO reports that only 41% of infants are exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life globally. The global impact of suboptimal breastfeeding practices is staggering, with an annual estimated cost of $341 billion in economic losses and resulting in the preventable deaths of 600,000 to 820,000 children annually. These outcomes could be avoided if all children under the age of 2 were breastfed. The CDC estimated that 46.5% of infants in the US were exclusively breastfed for the first 3 months in 2021. In the same year, 84.1% of infants had some exposure to HBM in the first 3 months, with 59.8% continuing at 6 months and 39.5% at 12 months. Healthy People 2030 objectives include increasing the proportion of exclusively breastfed infants through 6 months and 1 year. There has been little or no detectable change in these objectives from Healthy People 2020. The target is that 42.4% of infants will be exclusively breastfed until 6 months of age, in contrast to the current rate of 27.2%. The target for infants who are breastfed until 1 year is 54.1%, in contrast to the current rate of 39.5% (AAP, n.d.; ACOG, 2020; CDC, 2024; Hollier, 2021; Meek, 2024; Meek & Noble, 2022; North et al., 2022; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.; WHO, 2023).

Benefits

Extensive evidence demonstrates the benefits of breastfeeding for infants and breastfeeding parents. Even if a breastfeeding parent is ill, the antibodies produced by their body will pass to the infant. This passive immunity significantly decreases a breastfeeding infant's risk of becoming sick. Multiple studies have shown that infants experience a reduction in acute illnesses during the time they are breastfed (e.g., croup, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, or similar lower respiratory tract infections). Exclusive breastfeeding for a longer duration increases these benefits (AAP, n.d., 2021; Hollier, 2021; Meek, 2024).

Breastfeeding also has long-term benefits. The AAP cites evidence that breastfeeding offers protective benefits for infants born to families with a history of allergies compared to those who are formula fed. Specifically, infants exclusively breastfed for at least 4 months had a lower risk of developing cow's milk allergy, atopic dermatitis, eczema, and asthma. However, the long-term benefits of breastfeeding on allergies are not well understood, as studies have not thoroughly examined its impact on families without a history of allergies. Breastfed infants also have a reduced risk of gastrointestinal infections, necrotizing enterocolitis, childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis. Infants who breastfeed for more than 6 months are less likely to develop childhood acute leukemia and lymphoma as compared to those who receive formula. Although the etiology is not fully understood, studies indicate a 40% to 64% reduction in sudden infant death syndrome risk among breastfed infants. Research also suggests that breastfed infants are less likely to have a BMI over 30 in adolescence and adulthood and are less vulnerable to type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (AAP, 2021; Meek, 2024; Perez-Escamilla & Segura-Perez, 2025).

Parents also experience benefits from breastfeeding. Initiating breastfeeding after birth can decrease postpartum bleeding and the time of uterine involution. Over time, breastfeeding reduces an individual's risk of developing premenopausal ovarian, endometrial, and breast cancers, thyroid cancer, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Breastfeeding also promotes the bonding experience between a breastfeeding parent and their infant (AAP, 2021; Perez-Escamilla & Segura-Perez, 2025).

Breastfeeding also has economic benefits. Less waste (e.g., formula packaging, bottles, nipples, and other equipment) is deposited into landfills when families opt to breastfeed. Breastfeeding also reduces the overall cost of caring for an infant. Infant formula can financially burden families with limited income, costing $1,200 to $2,000 each year. Additionally, breastfeeding can protect parents from having to navigate finding formula during a shortage, such as the production drop and subsequent decrease in availability of infant formula seen in the US in 2022. Breastfeeding reduces absenteeism due to the benefits to the infant’s immune system and reduction in infant illnesses. It is also a time-saver because when an infant feeds directly from the breast, the HBM comes out at the ideal temperature for consumption and requires no prep time (Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2025a; Meek, 2024; Perez-Escamilla & Segura-Perez, 2025).

Contraindications

There are circumstances in which breastfeeding is contraindicated for the parent or infant. Infants diagnosed with galactosemia should not receive HBM. Breastfeeding is typically not advised for individuals who use illicit drugs or who have T-cell lymphotropic virus types I or II, untreated brucellosis, or suspected or confirmed Ebola virus disease. Caution and discussion are advised in patients with HIV. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP, 2022) suggests exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months and continued breastfeeding for 12 months, including for HIV-positive individuals who reside in areas with high rates of infant diarrhea and respiratory illness. The AAP advises that the risk of HIV transmission from breastfeeding in individuals who are on antiretroviral (ART) HIV therapy is 1%. They advise discussing the risks and benefits of breastfeeding with the patient. These individuals treated with ART HIV medications and their infants should be tested and treated adequately with ART HIV medications if indicated. Patients with herpes simplex lesions on the breast should avoid breastfeeding from the affected breast but are encouraged to continue breastfeeding from the contralateral side until the lesions heal. Breastfeeding parents with active tuberculosis, monkeypox virus infection, or active varicella infection should be quarantined away from their infant and not directly feed the infant from the breast. However, they can express HBM for another individual to feed the infant. In circumstances where breastfeeding is not viable, pasteurized donor HBM can be obtained from milk banks. Individuals with hyperlactation can donate their excess HBM to these banks to assist those unable to breastfeed (Abuogi et al, 2024; AAFP, 2022; AAP, 2021; CDC, 2025a, 2025b; Human Milk Banking Association of North America [HMBANA], n.d.; Meek & Noble, 2022; Pollock & Levison, 2023).

There are classes of medications that are not considered compatible for use while breastfeeding, including statins, amphetamines, ergotamines for migraines, and chemotherapeutic medications. Other medications can decrease the HBM supply (e.g., decongestants, estrogens, or dopamine agonists), and finding an alternative medication is recommended if possible. In 2014, the FDA amended the regulation governing the content and prescription labeling format for the pregnancy, labor and delivery, and breastfeeding section. Per the new regulation, all labeling must include the risks of using a particular medication during pregnancy and lactation. The National Library of Medicine maintains a database called LactMed on drugs and other chemicals that may be passed to infants through HBM. It includes information on the levels of these substances found in HBM, the amount transmitted to the infant, and possible adverse effects (FDA, 2025b; Kellams, 2024a; National Library of Medicine, n.d.).

Positioning

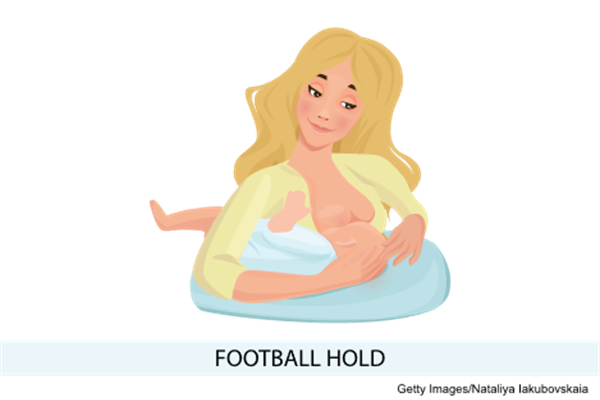

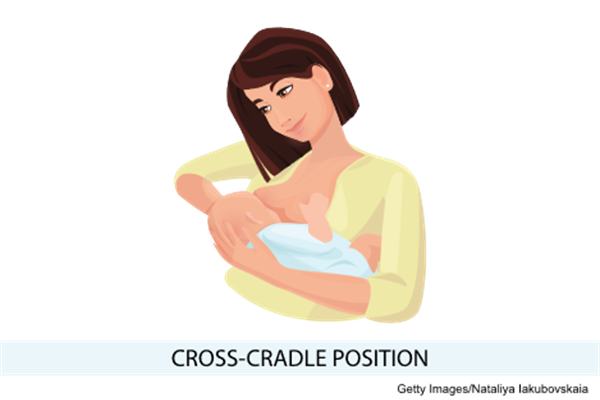

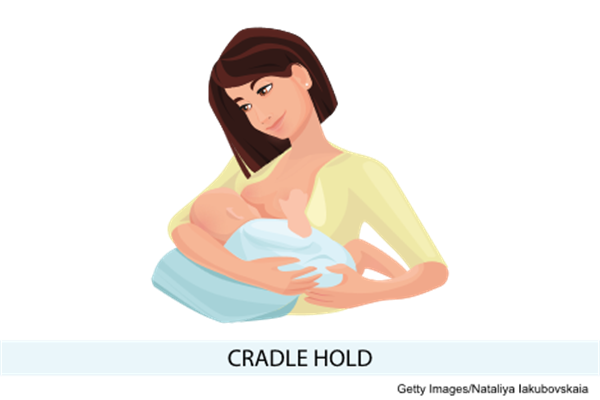

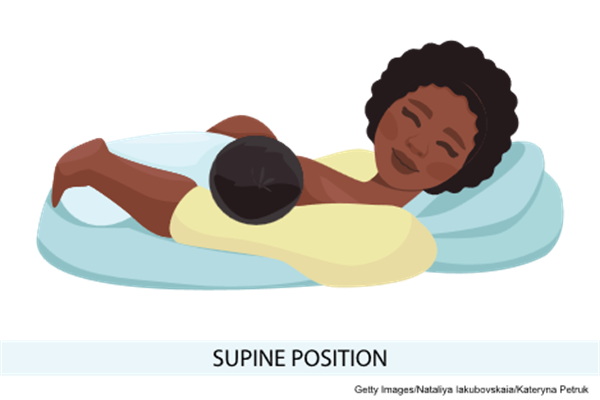

Nurses can instruct breastfeeding patients on multiple breastfeeding holds or positions, depending on the needs of the infant or parent. The most common positions are referred to as the football or clutch hold, the cross-cradle or across-the-lap hold, the cradle hold, the side-lying position, and the straddle or laid-back hold (refer to Figure 2; ACOG, 2020; Office on Women's Health [OASH], 2025).

- The football or clutch hold is helpful for patients who have had a cesarean birth or have large breasts, flat or inverted nipples, or a strong let-down reflex. The infant is held at the patient's side, lying on their back, with their head at the level of the nipple and their legs and feet extending along the patient's side and behind them. The patient supports the infant's head by placing their palm at the base of the infant's head.

- The cross-cradle or across-the-lap hold is helpful for premature infants or infants with a weak suck, as it gives extra head support and may help the infant stay latched. The infant is held with the contralateral arm while the infant's body faces the patient. The patient supports the infant's head by placing their palm at the base of the infant's head.

- The cradle hold is the most-used position. This position involves placing the infant's head on the patient's forearm near the elbow bend, with their body facing the patient.

- The side-lying position allows the patient to rest while the infant breastfeeds and is especially helpful after a cesarean birth. The patient lies on one side with the infant facing them.

- The straddle or laid-back hold is a more relaxed and infant-led approach. The patient lies back on a pillow and places the infant against their body with the infant's head just above and between the breasts. When hungry, the infant will gravitate to and wiggle toward a nipple. The patient supports the infant's head and shoulders as needed. An advantage of this hold is increased comfort for the patient and improved positioning for the child without occupying one or both of the patient's hands.

Figure 2

Football or Clutch Hold

Figure 3

Cross-Cradle or Across-the-Lap Hold

Figure 4

Cradle Hold

Figure 5

Side-Lying Position

Figure 6

Supine Position

Latching

An effective latch occurs "when the infant is attached to the breast, the border of the nipple-areolar complex and part of the areola is visible outside of the infant’s upper lip and the nose is free, while the infant’s chin is buried in the breast, with no areola showing outside the infant’s lower lip” (Kellams, 2024b). A proper latch is essential for successful breastfeeding (refer to Figures 7 and 8). Signs of a good latch include the following (OASH, 2025).

- The breastfeeding patient feels a firm tugging sensation on the nipple without pain.

- The infant's cheeks are rounded, not dimpled.

- The infant's jaw glides smoothly when sucking.

- Swallowing is audible.

- The infant's chin touches the breast.

- The areola is entirely in the infant's mouth.

- The infant's lips turn out.

- The infant's ears wiggle when sucking.

Figure 7

Good Latch

Figure 8

Shallow Latch

Infants may experience challenges with latching during breastfeeding. Several tips that nurses can share with patients include tickling the infant's lips with the nipple to entice the infant to open wide, drawing the infant close so their chin and lower jaw move into the breast first, and watching the infant's lower lip to aim it far from the base of the nipple, helping the infant enclose the areola. If breastfeeding is painful, the patient should break the infant's latch by placing a clean finger into the corner of the infant's mouth and then attempt to latch again. Breastfeeding should be comfortable and pain free. Infants may have ankyloglossia, more commonly known as "tongue-tie." These infants have a tight or short lingual frenulum, which is the piece of tissue attaching the tongue to the floor of the mouth. They may be unable to extend their tongue past their lower gum line or properly latch onto the breast, causing slow weight gain in the infant and nipple pain for the parent (Kellams, 2024b; OASH, 2025).

Indicators of Effective Feeding

One of the most common concerns among breastfeeding patients is that their infant is not receiving enough HBM. This is especially true in the early days of breastfeeding and is cited as the most common reason for early cessation of breastfeeding. To help alleviate these concerns, nurses should educate parents on the signs that indicate their infant is consuming enough HBM.

- The infant:

- Latches without difficulty

- Has at least six wet diapers and three to four bowel movements per day after the first week of life

- Has normal skin turgor and moist mucous membranes

- Has eight to 12 feedings in 24 hours

- Switches between short sleeping periods and wakeful, alert periods

- Is satisfied and content after feedings

- Easily releases the breast after feeding

- Has bursts of 15 to 20 sucks/swallows at a time

- The patient:

- Notices the breasts feel softer after feeding

- Feels relaxed and drowsy during feedings

- Notices increased thirst

- Leaks HBM from the contralateral breast during feedings (Hollier, 2021; Kellams, 2024a, 2024b; Spencer, 2024)

HBM Expression

HBM can be expressed from the breasts using hand or mechanical expression. The most common method used for HBM expression is pumping. Pumping is not usually recommended until a patient's HBM supply is well established and their infant can latch and breastfeed successfully. However, there are exceptions to this recommendation. If an infant is born premature or ill and requires medical intervention that prevents the parent from breastfeeding, pumping should be initiated as soon as possible following birth and continue at regular intervals until the infant can be breastfed. Pumping can also help if an infant is not latching correctly or has an issue with HBM transfer. It is also recommended that if breastfeeding is interrupted for any reason, the breastfeeding parent should pump to maintain a sufficient HBM supply. This is especially true if a breastfeeding parent must return to work outside the home or travel away from their infant (Kellams, 2024a).

Although HBM can be expressed by hand, an electric pump is more efficient. Most electric pumps allow breastfeeding parents to pump from both breasts simultaneously (i.e., double-pumping), decreasing the time commitment. The amount of HBM obtained when pumping depends on multiple variables, including the type of pump being used, time of day, time since the last pumping session or feeding, comfort level, and HBM supply. The Affordable Care Act requires Medicaid and most commercial health insurance policies to cover the cost of a breast pump. However, the insurance provider determines whether the pump is rented or purchased, electric or manual, and delivered before or after birth (ACOG, n.d.; Kellams, 2024a; US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, n.d.).

Storage of HBM

If HBM needs to be collected and not used immediately, it can be stored. Multiple factors (e.g., HBM volume, room temperature when HBM was expressed, temperature fluctuations in the refrigerator and freezer, and cleanliness of the environment) can affect how long HBM can be stored safely. The following CDC and US Department of Agriculture (USDA) guidelines cover the proper storage of HBM (refer to Figure 9; CDC, 2023a).

Figure 9

HBM Storage Guidelines

(CDC, 2023a)

Before storing or handling HBM, the caregiver should wash their hands with soap and water to prevent contamination. When HBM is expressed by hand or with a manual or electric pump, it should always be stored in specific HBM storage bags, clean, food-grade glass, or BPA-free plastic containers with tight-fitting lids. HBM should not be stored in the fridge or freezer door to ensure consistent temperatures during storage. If HBM will not be used within 4 days, freeze immediately after expressing it to ensure optimal quality. When filling storage containers for freezing, leave room in the container to allow for expansion. Label bags with the date the HBM was expressed and the amount for ease of use later. Frozen HBM can be safely stored in an insulated cooler with ice packs for up to 24 hours when traveling. The oldest HBM should always be thawed and used first. Thaw HBM in the refrigerator (use within 24 hours) or warm water if needed (use within 2 hours), but do not refreeze. Use of a microwave to heat HBM is not recommended, as this can destroy vital nutrients and create hot spots, which can cause burns. Instead, serve HBM cold, at room temperature, or heated in a sealed container in a bottle warmer or pot of warm water. Once an infant begins feeding with expressed HBM, contamination occurs. The recommendation in this situation is to discard any remaining HBM within 1 to 2 hours of the end of the feeding. However, there are many different variables, including bacterial load, and some individuals may feel more comfortable discarding any remaining HBM immediately after the feeding (CDC, 2023a, 2023b; LaLeche League USA, 2020).

Lactating parents who have returned to work and desire to continue breastfeeding will need to express their HBM regularly during the workday. Expressed HBM is considered food and should not be treated as a biohazard. HBM can be stored in the workplace refrigerator, among other stored food. In certain work environments, however, this practice may not be socially acceptable. Consequently, some individuals may prefer to store expressed HBM in a discreet container within the refrigerator or in a personal cooler with a freezer pack for added privacy and comfort (CDC, 2023b; LaLeche League USA, 2020).

Common Complications

Although most government and professional organizations recommend that infants be exclusively fed HBM for 6 months, it is common for individuals to experience problems that deter them from breastfeeding. Common issues faced by patients include engorgement, sore nipples, plugged ducts, low HBM supply, mastitis, and fungal infections. Preventatively, nurses should encourage patients to get as much sleep as possible, maintain adequate nutrition and fluid intake, and wear a supportive, well-fitting bra to prevent or minimize these problems (Spencer, 2024).

Engorgement

Engorgement occurs when the breasts are not fully emptied and accumulate HBM. This can happen during the transition from colostrum to mature milk or due to delayed or missed feedings or pumping sessions. Engorgement presents as breasts that are firm, warm, red, tender, full, and painful and may also be accompanied by a low-grade fever. Engorgement is usually self-limiting and resolves in a few days, but it can lead to plugged ducts or a breast infection if not addressed. Nurses should encourage patients to breastfeed first from the engorged breast. Applying a warm washcloth to the breasts or taking a warm shower before feeding will promote let-down and HBM flow. Engorgement may also affect the infant's ability to latch, so expressing a small amount of HBM before nursing or attempting a reverse-pressure softening massage while breastfeeding may make it easier for the infant to latch. The duration or frequency of feedings or pumping sessions should be increased to relieve symptoms and prevent further engorgement. If the patient is pumping, there should be no more than 4 hours between pumping sessions. Patients should feed their infant every 2 hours on one breast until soft, while pumping the other. Between feedings, cold compresses (15 to 20 minutes on and 45 minutes off) on the breasts can reduce swelling and pain. Placing raw cabbage leaves directly on the breasts between feedings can also help relieve discomfort. If needed, acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) can be used to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation (Hollier, 2021; Spencer, 2024).

Sore Nipples

Mild nipple sensitivity and soreness are expected in the early days of breastfeeding. Abnormal findings include soreness that becomes severe and a nipple that appears irritated, cracked, or bleeding. Sore nipples are often related to an incorrect latch or poor positioning. Therefore, achieving a good latch and proper positioning can help decrease nipple soreness and prevent further damage. For prevention and healing, patients can express a few drops of HBM and gently rub it on the nipples with clean hands after breastfeeding, as HBM has natural healing, soothing, and emollient properties. Education should also include allowing the nipples to air-dry after feeding and wearing soft cotton shirts. Breastfeeding patients should wear a supportive bra that is not too tight and does not put pressure on the nipples. Absorbent nursing pads should be changed often to keep the nipples clean and dry. Patients should avoid using harsh soaps or ointments that contain astringents on the nipples. They can wash their nipples and breasts with clean water. Creams, hydrogel pads, or a nipple shield may be used, but these are only advised after a consultation with a lactation specialist (Hollier, 2021; Kellams, 2024b; Niazi et al., 2021; Spencer, 2024).

Plugged Milk Ducts

A plugged duct occurs due to improper drainage, causing pressure to build within the duct and resulting in inflammation in the surrounding tissue. This condition usually affects one breast at a time and presents as a sore, tender lump with no associated fever. Common causes include poor feeding technique, not changing feeding positions, wearing a tight or ill-fitting bra, engorgement, infection, or a sudden decrease in feeding frequency. To treat a plugged duct, patients should breastfeed as often as every 2 hours on the affected side, massage the area behind and above the plugged duct, apply warm compresses, and wear a well-fitting, supportive bra (Hollier, 2021; Kellams, 2024b; Spencer, 2024).

Insufficient HBM Supply

Whether real or perceived, lactation insufficiency or low HBM supply is cited as the most common reason for discontinuation of breastfeeding. Lactation insufficiency can be caused by mammary tissue insufficiency, hormone imbalance, or ineffective HBM removal from the breast, triggering a negative feedback loop and decreasing HBM production. Some patients have difficulty producing enough HBM after a complicated labor, delayed breastfeeding initiation, separation due to preterm birth, formula substitution, cracked nipples, or maternal illness. A referral to a lactation consultant can assist with breastfeeding (Kellams, 2024a, 2024b; Spencer, 2024).

The first-line recommended treatments for low HBM supply are nonpharmacological, including ensuring a proper latch and positioning and increasing feeding frequency. These aim to naturally enhance HBM production before considering other options. The use of galactagogues (substances thought to increase HBM production) is common. One study involving 1,876 breastfeeding individuals found that 60% had used a galactagogue at some point. Prescription metoclopramide (Reglan) has been used off label as a galactagogue, as it increases prolactin levels and HBM production. Using herbs and food as galactagogues is a centuries-old practice. Examples include fenugreek, malt products, lactation cookies (containing ingredients such as fenugreek, oats, brewer’s yeast, and flaxseed), linseed, blessed thistle, alfalfa, fennel, raspberry leaf, and chamomile. Fenugreek is the most commonly used herb to increase HBM production. However, galactagogues are not recommended for routine use due to a lack of evidence to support efficacy and concerns over safety (Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges, 2024; McBride et al., 2021; Spencer, 2024).

Breastfeeding patients should be encouraged to focus on adequate hydration, frequently breastfeeding with a proper latch and positioning, pumping immediately after feeding to ensure the breasts are empty, and offering both breasts at each feeding to increase HBM supply. Education regarding the timing of expected growth spurts (2 to 4 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months) is helpful as the infant typically feeds more often during these times. This increased feeding is not indicative of an inadequate HBM supply. While the concern about not producing enough HBM is common, most breastfeeding patients produce enough HBM to feed their infants. Finally, patients should be educated on the signs of adequate infant nutrition, such as wet diaper and bowel movement frequency, behavioral signals of satiety, and weight gain (Hollier, 2021; Kellams, 2024a, 2024b; Spencer, 2024).

Mastitis

Mastitis is inflammation of the breast. It is usually, but not always, associated with an infection of the breast and may affect one or both breasts. Infection can occur at any time during lactation, but is most common during the first 6 weeks of breastfeeding. A majority of mastitis cases occur in the superior lateral portion of the breast (Hollier, 2021; Spencer, 2024). Signs and symptoms of mastitis include:

- breast tenderness and warmth

- breast swelling

- thickening of breast tissue

- pain or burning sensation continuously or while breastfeeding

- skin redness, possibly in a wedge-shaped pattern

- yellowish discharge from the nipple resembling colostrum

- fever of 101° F (38.3° C) or greater

- nausea and vomiting

- flulike symptoms, muscle aches, chills, and malaise (Blackmon et al., 2024; Dixon & Louis-Jacques, 2023; Hollier, 2021; Spencer, 2024)

HBM stasis, or inadequate breast emptying, is often the initial causative factor for mastitis. All breastfeeding patients should be educated on the importance of adequate hydration, rest, frequent feedings, minimizing the use of pumps, and avoiding nipple shields. Mastitis can also be related to plugged ducts, engorgement, abrupt weaning, sore and cracked nipples, and wearing a bra with underwire or that is too tight. Stress, fatigue, illness, and poor maternal nutrition can also provoke mastitis. Patients with mastitis should breastfeed or pump more frequently (at least every 2 hours) by starting on the affected breast, positioning the infant at the breast with the chin or nose pointing toward the blockage, massaging the breast from the blocked area(s) to the nipple, and expressing HBM to assist with drainage. Initial mastitis treatment focuses on symptom management and education. However, a 10-day course of antibiotics may be needed if symptoms do not improve within 12 to 24 hours or if the patient becomes acutely ill. The most common pathogen in mastitis is Staphylococcus aureus. The preferred antibiotics are dicloxacillin (Dycill) or cephalexin (Keflex). If not tolerated or allergic, clindamycin (Cleocin) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole DS (Bactrim DS) can be substituted. To help alleviate edema and inflammation, the patient may use ice packs or over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin; Blackmon et al., 2024; Dixon & Louis-Jacques, 2023; Spencer, 2024).

Fungal Infection

Fungal infections can form on the nipple or the breast due to an overgrowth of the Candida organism. Signs of a fungal infection include:

- nipple soreness lasting more than a few days and out of proportion to any apparent cause

- pink, flaky, shiny, itchy, or cracked nipples

- deep pink and blistered nipples

- breasts that ache

- shooting pains in the breast during or after feedings

- infant with oral candidiasis (thrush; Spencer, 2024)

Topical antifungals miconazole (Azolen) or clotrimazole (Alevazol) are preferred over nystatin (Nyamyc) due to decreased risk of resistance. Mupirocin (Bactroban) or bacitracin (Baciguent) can be added if there is fissuring present. The medications should be applied directly to the affected area on the nipple and removed using a food-grade oil (e.g., coconut or olive oil) just prior to each feeding. For resistant cases, oral fluconazole (Diflucan) treatment is typically recommended for 2 weeks. Ketoconazole (Nizoral) is contraindicated due to the possibility of infant hepatotoxicity, and gentian violet is not recommended due to mucous membrane toxicity, carcinogenic and hypersensitivity potential, and permanent staining of the skin. During treatment, patients can continue breastfeeding. Fungal infections can take weeks to resolve. To avoid spreading the infection, patients should change disposable nursing pads often, wear a clean bra daily, and wash their hands and the infant's hands often. Infants should be observed for indications of oral thrush or may be treated prophylactically (Hollier, 2021; Spencer, 2024).

Breastfeeding Promotion in Hospitals

The WHO and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) launched the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) to help motivate facilities providing maternity and newborn services worldwide to implement the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (refer to Table 4). A recent study of almost 20,000 infants had a reduction of emergency department admissions in the year after implementing the BFHI program. The implementation guidance for BFHI emphasizes strategies to scale up to universal coverage and ensure sustainability over time. The goal is to integrate the program fully into the health care system and ensure all facilities in a country implement the steps uniformly (Harrison-Long et al., 2023; UNICEF & WHO, 2018).

Table 4

Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding

Critical management procedures | 1.

|

| 2.

|

Key clinical practices | 3.

|

4.

| |

5.

| |

6.

| |

7.

| |

8.

| |

9.

| |

10.

|

(UNICEF & WHO, 2018)

Supporting Breastfeeding

Considering the well-documented health benefits of breastfeeding for both parents and infants, it is imperative to provide robust support to breastfeeding parents and to promote greater social acceptance of breastfeeding practices. Public health initiatives seek to ensure the right to breastfeed, increase the rate of initiating and maintaining exclusive breastfeeding in the US, raise awareness of breastfeeding benefits, and expand breastfeeding research (US Breastfeeding Committee [USBC], n.d.). Refer to Table 5 for the most up-to-date US policies, programs, and initiatives.

Table 5

Federal Policies, Programs, and Initiatives

| Current Federal Policies and Resources | Current Federal Programs That Include Breastfeeding | Current Federally Funded Initiatives |

Health Care | Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (Health Resources & Services Administration [HRSA], 2016) | Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant program (USDA) | EMPower Best Practices (CDC) |

| Breastfeeding: Primary Care Interventions (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2016) | Healthy Start (Maternal and Child Health Bureau [MCHB]) | Continuity of Care in Breastfeeding Support (CDC) |

| Primary Care Interventions to Promote Breastfeeding (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2015) | Head Start (Administration for Children & Families) | Breastfeeding Physician Education & Training Project Advisory Committee (CDC) |

| HIS Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (Indian Health Service, 2013) | National Immunization Surveys (CDC) | |

| Infant Feeding Practices Study II (CDC) | ||

| Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care survey (CDC) | ||

| Healthy People 2030 (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP]) | ||

| Healthy People 2020 Law and Health Policy project (ODPHP) | ||

Mothers, Parents, and Families | WIC Breastfeeding Support: Learn Together. Grow Together. (USDA, 2018) | National Action Partnership to Promote Safe Sleep Improvement and Innovation Network (MCHB) | |

| Your Guide to Breastfeeding (OASH, 2017) | ||

| It’s Only Natural (OASH, 2014) | ||

| Safe to Sleep (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2012) | ||

Employment | Supporting Nursing Moms at Work (OASH, 2019) | ||

| Apoyo a lactancia materna en el trabajo (OASH, 2019) | ||

| Employment Protections for Workers Who Are Pregnant or Nursing (US Department of Labor, 2015) | ||

| Nursing Mothers in Federal Employment (US Office of Personnel Management [OPM], 2010) | ||

| Guide for Establishing a Federal Nursing Mother’s Program (OPM, 2013) | ||

Research | Breastfeeding Report Card (CDC, biannual) | ||

| Maternal and Fetal Effects of Mental Health Treatments in Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women: A Systematic Review of Pharmacological Interventions (AHRQ, 2019) | ||

| Breastfeeding Programs and Policies, Breastfeeding Uptake, and Maternal Health Outcomes in Developed Countries (AHRQ, 2018) | ||

| Pregnancy and Birth to 24 months (USDA, 2012) | ||

Cross-Sector | The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies (CDC, 2013) | ||

| The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding (Office of the Surgeon General [OSG], 2011) | ||

| National Prevention Strategy (OSG, 2011) | ||

Communities | Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (HRSA) | ||

| Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC; USDA) | ||

| Child and Adult Care Food Program (USDA) | ||

Public Health Infrastructure | Children’s Healthy Weight Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network (MCHB) |

(USBC, n.d.)

The previously described policies, programs, and initiatives include the following.

- Protecting individuals who choose to breastfeed in public and private locations with legislation, while ensuring breastfeeding is not included in indecency legislation

- Launching public health campaigns that encourage individuals of all cultures to breastfeed, especially families of African American, Indigenous Peoples, and Asian‐Pacific Islander descent

- Allowing lactation to qualify as a valid exemption from jury duty (or deferral of service for a year)

- Ensuring WIC and the CDC have adequate funding and support for peer counselors, federal breastfeeding campaigns, and other resources

- Ensuring public and private health insurance plans adequately cover lactation services and breastfeeding supplies (scales, pumps)

- Requiring support of lactating patients in the workplace with requisite breaks and private areas (not bathrooms) to pump or breastfeed through legislation and corporate policy

- Supporting to establish and maintain exclusive breastfeeding and flexible scheduling to continue breastfeeding for up to a year through paid maternity leave via enhanced family medical leave policies

- Ensuring the CDC, AHRQ, USDA, and other organizations receive adequate funding for breastfeeding research

- Clarifying the marketing recommendations for artificial nipples/bottles within the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes

- Developing and maintaining nurse home-visiting programs to help patients with breastfeeding after discharge through funding and other suppor

- Establishing or improving access to donor HBM through enhanced insurance coverage in public and private plans for infants admitted to NICUs

- Introducing the Proxy Voting for New Parents Resolution, the Bottles and Breastfeeding Equipment Screening (BABES) Enhancement Act, and the Jobs Protection Act into legislation in 2025 (ACOG, n.d.; HMBANA, n.d.; USBC, n.d.)

References

Abuogi, L., Noble, L., & Smith, C. (2024). Infant feeding for persons living with and at risk for HIV in the United States: Clinical report. Pediatrics, 153(6), e2024066843. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2024-066843

American Academy of Family Physicians. (2022). Breastfeeding, family physicians supporting (position paper). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding-position-paper.html

American Academy of Pediatrics. (n.d.). Breastfeeding. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/baby/breastfeeding/Pages/default.aspx

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2021). Breastfeeding overview. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-overview

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Understanding health care coverage for breastfeeding. Retrieved April 15, 2025, from https://www.acog.org/programs/breastfeeding/understanding-health-care-coverage-for-breastfeeding

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2020). Breastfeeding your baby: Breastfeeding positions. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/infographics/breastfeeding-your-baby-breastfeeding-positions

Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges. (2024). Herbal support for lactation: Boosting milk supply naturally. https://aanmc.org/naturopathic-treatment/herbal-lactation-support/

Blackmon, M. M., Nguyen, H., Vadakekut, E. S., & Mukherji, P. (2024). Acute mastitis. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557782

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023a). Breast milk storage and preparation. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breast-milk-preparation-and-storage/handling-breastmilk.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023b). Breast milk storage questions and answers. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/php/guidelines-recommendations/faqs.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). NIS-child data results. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/survey/results.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025a). Contraindications to breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/hcp/contraindications/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025b). HIV and breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/hcp/illnesses-conditions/hiv.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025c). mPINC™ national report. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/mpinc/national-report.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025d). Vitamin D and breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/hcp/diet-micronutrients/vitamin-d.html

Colleluori, G., Perugini, J., Barbatelli, G., & Cinti, S. (2021). Mammary gland adipocytes in lactation cycle, obesity, and breast cancer. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 22, 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-021-09633-5

Dixon, J. M., & Louis-Jacques, A. (2023). Lactational mastitis. UpToDate. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lactational-mastitis

Harrison-Long, C., Papas, M., & Paul, D. A. (2023). The impact of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative on healthcare utilization among newborns insured by Medicaid in Delaware. BMC Pediatrics, 23(1), 613. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04424-0

Heo, J. S., Ahn, Y. M., Kim, A. E., & Shin, S. M. (2022). Breastfeeding and vitamin D. Clinical and Experimental Pediatrics, 65(9), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2021.00444

Hollier, A. (Ed.). (2021). Clinical guidelines in primary care (4th ed.). Advanced Practice Education Associates.

Human Milk Banking Association of North America. (n.d.). About. Retrieved April 15, 2025, from https://www.hmbana.org/about-us/

Kalarikkal, S. M., & Pfleghaar, J. L. (2023). Breastfeeding. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534767/

Kellams, A. (2024a). Breastfeeding: Parental education and support. UpToDate. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/breastfeeding-parental-education-and-support

Kellams, A. (2024b). Initiation of breastfeeding. UpToDate. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initiation-of-breastfeeding

Kim, S. Y., & Yi, D. Y. (2020). Components of human breast milk: From macronutrient to microbiome and microRNA. Clinical Experimental Pediatrics, 63(8), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2020.00059

LaLeche League USA. (2020). Storing human milk. https://lllusa.org/storing-human-milk/

McBride, G. M., Stevenson, R., Zizzo, G., Rumbold, A. R., Amir, L. H., Keir, A. K., & Grzeskowiak, L. E. (2021). Use and experiences of galactagogues while breastfeeding among Australian women. PLOS ONE, 16(7), e0254049. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254049

Meek, J. Y. (2024). Infant benefits of breastfeeding. UpToDate. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/infant-benefits-of-breastfeeding

Meek, J. Y., & Noble, L. (2022). Policy statement: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 150(1), e2022057988. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057988

National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Drugs and lactation database (LactMed®). Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/

Niazi, A., Rahimi, V. B., Askari, N., Rahmanian-Devin, P., & Askari, V. R. (2021). Topical treatment for the prevention and relief of nipple fissure and pain in breastfeeding women: A systematic review. Advances in Integrative Medicine, 8(4), 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aimed.2021.07.001

North, K., Gao, M., Allen, G., & Lee, A. C. C. (2022). Breastfeeding in a global context: Epidemiology, impact, and future directions. Clinical Therapeutics, 44(2), 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.11.017

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Healthy people: Nutrition and healthy eating. US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved April 15, 2025, from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/nutrition-and-healthy-eating

Office on Women’s Health. (2025). Getting a good latch. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding/learning-breastfeed/getting-good-latch

Perez-Escamilla, R., & Segura-Perez, S. (2025). Maternal and economic benefits of breastfeeding. UpToDate. Retrieved April 15, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/maternal-and-economic-benefits-of-breastfeeding

Pillay, J., & Davis, T. J. (2023). Physiology, lactation. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499981

Pollock, L., & Levison, J. (2023). 2023 updated guidelines on infant feeding and HIV in the United States: What are they and why have recommendations changed. Topics in Antiviral Medicine, 31(5), 576–586. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38198669/

Rivard, A. B., Galarza-Paez, L., & Peterson, D. C. (2023). Anatomy, thorax, breast. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519575/

Rogers, J. L., & Brashers, V. L. (Eds.). (2023). McCance and Huether's pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children (9th ed.). Elsevier.

Shah, R., Sabir, S., & Alhawaj, A. F. (2022). Physiology, breast milk. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539790/

Spencer, J. (2024). Common problems of breastfeeding and weaning. UpToDate. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/common-problems-of-breastfeeding-and-weaning

United Nations Children’s Fund & World Health Organization. (2018). Protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services: The revised Baby-Friendly-Hospital Initiative. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513807#cms

US Breastfeeding Committee. (n.d.). Federal policies, programs, & initiatives. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from http://www.usbreastfeeding.org/federal-policies-programs--initiatives.html

US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (n.d.). Health benefits & coverage: Breastfeeding benefits. Retrieved April 15, 2025, from https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/breast-feeding-benefits

US Food & Drug Administration. (2025a). Infant formula. https://www.fda.gov/food/resources-you-food/infant-formula

US Food & Drug Administration. (2025b). Pregnancy and lactation labeling resources. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling-information-drug-products/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-resources

World Health Organization. (2023). Infant and young child feeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding

Ziomkiewicz, A., Babiszewska, M., Apanasewicz, A., Piosek, M., Wychowaniec, P., Cierniak, A., Barbarska, O., Szołtysik, M., Danel, D., & Wichary, S. (2021). Psychosocial stress and cortisol stress reactivity predict breast milk composition. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 11576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90980-3

Powered by Froala Editor