About this course:

The purpose of this course is to ensure nurses and other health care providers (HCPs) understand the New York State (NYS) laws about child maltreatment and their role in identifying and reporting potential cases of maltreatment.

Course preview

Child Maltreatment Recognition and Reporting in New York State

After this activity, learners will be prepared to:

- define child maltreatment, child abuse, and child neglect as recognized by NYS laws

- consider the incidence and prevalence of child maltreatment and abuse in NYS and the US

- identify the risk factors that contribute to child maltreatment and abuse and the mitigating effects of protective factors

- recognize the behaviors and physical indicators of child maltreatment and abuse, including in a virtual setting, and how bias affects the decision-making of health care providers (HCPs)

- recognize the indications of intellectual or developmental delays/disability and how this diagnosis affects the indicators of maltreatment or abuse

- explore the impact of trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and how to connect individuals/families with available services

- discuss when and how to report suspected cases of child maltreatment and abuse as a mandated reporter

- review the legal protection for mandatory reporting and consequences for failing to report suspected child maltreatment and abuse

The government, healthcare workers, teachers, family, friends, and parents are all partners in children’s growth, development, and safety. In a perfect world, all these components would work together for the good of each child, but statistics demonstrate that children are often victims of maltreatment and abuse. Children have a right to protection from harm, as reflected in current legal standards. When persons who are legally responsible (PLRs) for children fail to deliver proper care, legal consequences are imposed. Laws protect caregivers’ ability to raise their children as they view appropriate and hold them accountable for maintaining each child’s safety and protecting them from abuse or neglect. The US Constitution outlines this right to families in the 14th Amendment, “no state shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law (Congress.gov, section 1).”

While the US Constitution recognized the parental right to have children, there were no laws initially to protect them. Child abuse and maltreatment were mostly tolerated during this time until a wave of reform began. Between 1820 and 1870, the massive influx of immigration resulted in a seven-fold increase in the population of New York City, resulting in unregulated crime and child cruelty. The first laws protecting children were established in 1875 through a nongovernmental agency in New York, The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NYSPCC). Federal child protection did not occur until 1912 when Congress determined that the government must ensure children were protected from abuse. Congress formed the Children’s Bureau, which has focused on improving the lives of children and their families (NYSPCC, 2022).

New York passed its first Child Protective Services Act in 1973, which mandated reporting suspected child abuse and a 24-hour, 7-day-per-week registry to receive reports. The first federal law to protect children and improve the response to child abuse and neglect was The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) of 1974, which was not enacted until 2000. This act authorized law enforcement to implement child abuse and neglect laws and promoted child abuse prevention programs. It also developed a system to track suspected child abuse offenders (US Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2014). In 2011, the child abuse and prevention law in New York was updated to include an expanded list of mandatory reporters. The 2019 Child Victim’s Act in New York, providing alternatives for justice for victims of child abuse or sexual abuse, was enacted to allow civil charges against perpetrators. Laws guiding the New York Child Protective Services (2014) today include Title 6 of the Chapter 55 Social Services Law (specifically sections 411-428) and Article 10 of the Family Court Act (2021, section 1012; New York Child Protective Services, 2014; New York State Office of Children and Family Services [OCFS], 2024;). This module will focus on the NYS Consolidated Laws and mandatory child abuse identification and reporting for HCPs.

Definitions

In NYS, an abused child is defined as anyone under 18 years of age who experiences any of the following from a caregiver or another adult legally responsible for their care (New York Family Court Act, 2021, subsection e; New York Child Protective Services, 2022):

- “(i) inflicts or allows to be inflicted upon such child physical injury by other than accidental means which causes or creates a substantial risk of death, or serious or protracted disfigurement, or protracted impairment of physical or emotional health or protracted loss or impairment of the function of any bodily organ, or

- (ii) creates or allows to be created a substantial risk of physical injury to such child by other than accidental means which would be likely to cause death or serious or protracted disfigurement, or protracted impairment of physical or emotional health or protracted loss or impairment of the function of any bodily organ, or

- (iii) (a) commits or allows to be committed an offense against such child defined in Article 130 of the penal law; (b) allows, permits, or encourages such child to engage in any act described in sections 230.25, 230.30, 230.32 and 230.34-a of the penal law (promoting prostitution in the first, second or third-degree); (c) commits any of the acts described in sections 255.25, 255.26 and 255.27 of the penal law (incest); (d) allows such child to engage in acts or conduct described in Article 263 of the penal law (sexual performance by a child); or (e) permits or encourages such child to engage in any act or commits or allows to be committed against such child any offense that would render such child either a victim of sex trafficking or a victim of severe forms of trafficking in persons pursuant to 22 USC. 7102 as enacted by public law 106-386 or any successor federal statute.”

Child maltreatment refers to a failure to provide the minimum degree of care, resulting in impairment or imminent danger of impairment to a child’s physical, mental, or emotional condition. Maltreatment can occur when a PLR harms a child, places a child in imminent danger through failure to deliver the minimum level of care, or fails to provide a child with shelter, food, clothing, medical care, or education when...

...purchase below to continue the course

Child abuse refers to the most severe type of harm to children, in which a caregiver or a responsible individual inflicts or creates a significant risk of severe physical/bodily injury or commits sexual abuse acts against anyone under the age of 18, as defined by the New York laws above (OCFS, n.d.-b, 1st paragraph; PEPR, 2025).

A neglected child is a child under 18 years of age (New York Family Court Act, 2021, subsection f):

- “(i) whose physical, mental, or emotional condition has been impaired or is in imminent danger of becoming impaired as a result of the failure of his parent or another PLR for his care to exercise a minimum degree of care

- (A) in supplying the child with adequate food, clothing, shelter, or education in accordance with the provisions of part 1 of article 65 of the education law, or medical, dental, optometry, or surgical care, though financially able to do so or offered financial or other reasonable means to do so, or, in the case of an alleged failure of the respondent to provide education to the child, notwithstanding the efforts of the school district or local educational agency and child protective agency to ameliorate such alleged failure prior to the filing of the petition; or

- (B) in providing the child with proper supervision or guardianship, by unreasonably inflicting or allowing to be inflicted harm, or a substantial risk thereof, including the infliction of excessive corporal punishment; or by misusing a drug or drugs; or by misusing alcoholic beverages to the extent that they lose self-control of their actions; or by any other acts of a similarly serious nature requiring the aid of the court; provided, however, that where the respondent is voluntarily and regularly participating in a rehabilitative program, evidence that the respondent has repeatedly misused a drug or drugs or alcoholic beverages to the extent that they lose self-control of their actions shall not establish that the child is a neglected child in the absence of evidence establishing that the child’s physical, mental, or emotional condition has been impaired or is in imminent danger of becoming impaired as set forth in paragraph (i) of this subdivision; or

- (ii) who has been abandoned, in accordance with the definition and other criteria set forth in subdivision 5 of section 384-b of the social services law, by their parents or another PLR for their care.”

The subject of the report or alleged perpetrator must be “a parent of, guardian of, or other person 18 years of age or older legally responsible (PLR) for, as defined in subdivision (g) of section 1012 of the New York Family Court Act, a child reported to the statewide central register of child abuse and maltreatment (SCR) who is allegedly responsible for causing injury, abuse or maltreatment to such child or who allegedly allows such injury, abuse or maltreatment to be inflicted on such child; or a director or an operator of, or employee or volunteer in, a home operated or supervised by an authorized agency, the office of children and family services, or in a family daycare home, a daycare center, a group family day care home, a school-age child care program or a day-services program who is allegedly responsible for causing injury, abuse or maltreatment to a child who is reported to the SCR or who allegedly allows such injury, abuse or maltreatment to be inflicted on such child” (New York Child Protective Services, 2022, subsection 4).

Trauma is the response to an intense life-threatening or catastrophic event such as violence or abuse (Professional Education Program Review [PEPR], 2025).

Nursing alert: Many individuals may be involved in the abuse or maltreatment of a child. According to the NYS statutes, the perpetrator of abuse is responsible, and any person who is aware and allows the abuse to continue, including HCPs. Therefore, HCPs must be vigilant in identifying and reporting suspected child abuse or maltreatment (New York Child Protective Services, 2022, subsection 4). |

Epidemiology

According to the Administration for Children and Families (ACF, 2025), over 4.3 million children were subjects of investigation in 2023, and almost 550,000 were determined to be victims of maltreatment, decreasing from 678,000 in 2018. This number equates to a victim rate of 7.4 per 1,000 children. Of these, neglect was experienced by 64.1%, multiple types of maltreatment by 11.1%, physical abuse by 10.6%, sexual abuse by 7.5%, and psychological maltreatment (emotional abuse) by 3.5%. Due to abuse and neglect, child fatalities increased in 2023 to an estimated 2,000 children, a rate of 2.73 per 100,000 children. Of these child fatalities, 44% were younger than 1 year, a rate of 24.11 per 100,000 children in that age range. Males have higher fatality rates (3.15 per 100,000 males) than females (2.30 per 100,000 females). Black children have a 3.1 times greater fatality rate (6.04 per 100,000) than White children (1.94 per 100,000) and a 3.4 times greater rate than Hispanic children (1.76 per 100,000; ACF, 2025).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2024c), 1 in 7 children has experienced abuse across the US in the past year. Children who live in poverty experience abuse rates 5 times higher than their higher socioeconomic counterparts. The lifetime economic burden associated with child abuse is estimated at nearly $600 billion, which is comparable to high-cost diseases such as type 2 diabetes and stroke (CDC, 2024c).

The following are additional national statistics on child abuse (ACF, 2025):

- It is estimated that 66.9% of deaths related to abuse involved children under 3 years of age.

- Children under 1 year of age have the highest victimization rate at 21.0 per 1,000 children nationwide.

- Females have a higher victimization rate (7.9) than males (6.9) per 1,000 children.

- Indigenous children have the highest victimization rate (13.8), and African American children have the second-highest rate (11.9) per 1,000 children in that population.

- In 2023, parents—either individually or with another parent—were responsible for 89% of child abuse or neglect cases, with 37.2% committed by the mother alone, 24.6% committed by the father alone, and 19.4% involved both parents.

- More than half of perpetrators are female (51.6%), while 47.3% are male. Most perpetrators are between 25 and 44 years of age (69.2%). The largest percentage of perpetrators identified was White (46.6%), followed by Black (21.5%) and Hispanic (20.5%).

The OCFS Child Protective Services (CPS) Report includes 143,836 cases statewide in 2024 of alleged child abuse or maltreatment. Over 95% of these reports involved neglect, and 21% involved physical abuse (as many instances involved multiple allegation categories). 20% of the cases filed in 2024 (29,555 cases) were eventually determined to be indicated (i.e., substantiated), 12% (17,731) were placed on an alternative track (called family Assessment Response of FAR), and 64% (93,061) were determined to be unfounded. Only 11.8% of CPS reports were filed by a medical or mental health professional, while 25% were filed by social services personnel, 18% by educational personnel, and 16% by legal/law enforcement personnel (OCFS, 2025). NYS statistics on child fatalities in 2022 include the following (OCFS, 2023):

- The total number of alleged or suspicious deaths reported to SCR in 2022 in NYS was 249.

- The total number of substantiated deaths in 2022 in NYS related to child maltreatment and abuse was 92, and 15% (37 deaths) remained pending at the time of the official report publication in August of 2023.

- In 2022, 66 of the 249 fatalities occurred due to unsafe sleep conditions, representing 35% of all infant fatalities. The majority (66%) of these were infants asleep in adult beds.

Long-Term Effects

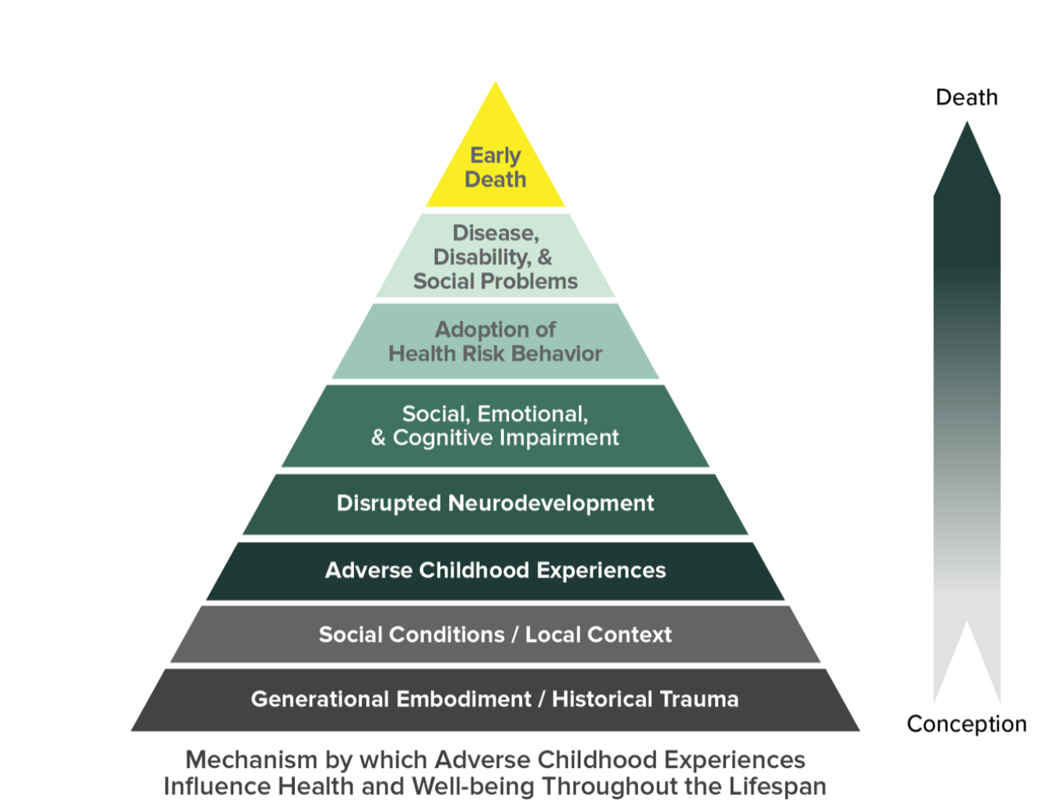

Child abuse and neglect leave a long-lasting impact on survivors; Figure 1 highlights the potential concerns with adverse childhood experiences (ACE) over a lifetime:

Figure 1

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Pyramid

(CDC, 2021)

ACEs can include experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect or witnessing violence in the home or community. Approximately 64% of adults in the US reported experiencing at least one ACE before the age of 18. The child’s environment can also have a significant impact on their sense of safety and stability. The presence of mental health conditions, substance use, or caregiver separation (e.g., divorce, imprisonment) in a household can all negatively impact the children within the household physically and mentally. Abuse and neglect cause physical changes in children’s brains. Poor impulse control, an inability to experience pleasure, or antisocial behaviors can stem from previous abuse and neglect. A child who lives in an unstable environment with constant stress or violence (also referred to as toxic stress) is more likely to develop learning disabilities, anxiety, and even physical illness, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and early death. Childhood maltreatment has also been associated with increased episodes and severity of depression, anxiety, and an increased risk of suicide attempts. Children exposed to violence are more likely to have poor school performance and develop substance use disorders (SUDs) and a variety of emotional and physical health concerns. Additionally, they may experience difficulties with interpersonal relationships, both with peers in the present and the future, as well as with maintaining a job and managing finances. Confounding factors that may intensify the effects of ACEs include discrimination, racism, poverty, and generational trauma (CDC, 2024a; Lippard & Nemeroff, 2019; PEPR, 2025).

Exposure to violence in children (under the age of 18) was assessed during the third National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence, or NatSCEV III, a joint effort of the CDC and the US Department of Justice in 2014. Most (67.5%) of respondents had witnessed violence or abuse directly or indirectly in the last year (when a crime was included in the definition of violence or abuse). Even more troubling was that 41% had multiple exposures in the past year, which could be trauma-inducing if not identified and adequately addressed. Up to 10% of the respondents reported six or more direct exposures in the last year, making them highly vulnerable to adversities and distress, or “polyvictims.” Exposure to violence can cause many of the same emotional and psychological effects as direct maltreatment if not managed appropriately. In addition, NatSCEV found that exposure to violence increased the risk of other types of violence/maltreatment as well (Finkelhor et al., 2015). In a more recent literature review, di Giacomo and colleagues (2021) found a relationship between trauma and psychopathy, with emotional neglect and physical abuse being the types of abuse with the strongest relationship to the development of psychopathy. Sexual abuse did not show a significant relationship to psychopathy in most of the studies reviewed (di Giacomo et al., 2021).

HCPs play an important role in the prevention and identification of ACEs. Understanding what constitutes an ACE and the risk factors associated with ACEs is key to prevention and appropriate care for children who are at risk of or experienced an ACE. Research has shown that many HCPs do not routinely ask about or screen for ACEs due to a lack of training on how to screen and talk with families about ACEs. Incorporating training for HCPs and developing protocols and guidelines for screening for ACEs will help identify children at risk of or who have experienced an ACE. HCPs should discuss with caregivers the importance of creating a safe, stable, and nurturing environment while addressing negative caregiving techniques and reinforcing positive ones. Formal programs such as the Safe Environment for Every Kid can be used to screen for ACE exposures and should be routinely incorporated into practice (Jones et al., 2020; OCFS, n.d.-a).

Resilience is defined as the ability to recover after a challenge or difficulty. Resilience mitigates the negative effects of ACEs. The following protective factors may increase resilience:

- supportive/caring relationships or connections

- economic stability

- social programming that takes into account the culture and background of participants

- early education and quality childcare

- components of a healthy lifestyle (e.g., exercise, sleep, diet, mindfulness; OCFS, n.d.-a)

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a significant increase in the use of telemedicine, also known as virtual visits. HCPs must remain vigilant in screening for and identifying signs and symptoms of child abuse and maltreatment even when they are interacting in a virtual environment. Several strategies can be employed by HCPs when interacting in a virtual environment, including:

- utilizing a standardized approach to screening for child abuse or maltreatment

- observe caregiver/child interactions (e.g., does the child seem afraid of the caregiver, behave differently when certain people are in the room or make concerning statements)

- observe non-verbal cues (i.e., expressions of pain, visible marks)

- consider known risk and protective factors when interacting with a child and family

- observe the background (i.e., safety hazards, yelling by family members)

- ask probing questions (i.e., what does a day at home look like)

- evaluate suspicious injuries by requesting photos using a secure message

- listen to how the caregiver describes interactions with the child

- use reliable technology with adequate lighting and sound

- ensure the child is present for at least a portion of the visit

- ask for introductions for everyone in the room with the child

- ask if the environment is sufficiently private

- ask for the physical location in case emergency services are needed

- if unsure, repeat observations to the caregiver and patient and inquire if they agree

- provide contact information for additional follow-up (North Central Missouri Children’s Advocacy Center, 2020; PEPR, 2025)

Risk and Protective Factors

Certain characteristics (direct or indirect) are associated with a greater likelihood of child abuse and maltreatment (Boos, 2025; CDC, 2024f). These risk factors occur in three main categories: (a) risk factors for victimization, (b) risk factors for perpetration, and (c) community risk factors (i.e., social determinants of health [SDOH]). Although child abuse and maltreatment can affect all races, ethnicities, sexes, and socioeconomic groups, research demonstrates that some of these characteristics are associated with an increased likelihood of abuse (Joyce et al., 2023). Therefore, identifying and understanding these risk factors is crucial for developing effective preventive initiatives. The risk factors for abuse and maltreatment in children at the individual and environmental level include:

- age 4 years old or younger, particularly premature babies

- special needs (emotional or physical) that can increase the caregiver’s burden

- failure to thrive

- attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity in children

- prematurity and low birth weight

- unplanned pregnancy

- unwanted child

- domestic/intimate partner violence in the home, including abusive, coercive, forceful, or threatening acts or words by a member of the household to another (the caregiver may be the perpetrator or victim of the domestic abuse) or other violence, including a caregiver’s personal history of child abuse or neglect

- animal cruelty

- financial problems within the family, leading to an inability to provide appropriate resources to meet the minimum needs of the children and family

- caregiving stress or negative interactions/caregiver-child relationships

- divorce, family break-ups, or social isolation

- living in poverty

- family mental health issues, including depression

- transient, non-biological male caregivers in the home, such as a caregiver’s significant other or partner (Boos, 2025; CDC, 2024f)

Caregiver risk factors that contribute to child abuse or maltreatment include:

- alcohol use disorder (compulsive and chronic use of alcohol)

- SUD (chronic, compulsive use of either prescription or illegal drugs)

- specific caregiver characteristics, including prior history of abuse, young age, low education, single parenthood, many dependent children, high stress, or low income

- unrealistic expectations for the child; a caregiver’s lack of understanding or negative perception regarding the needs or development of their child

- a lack of parenting skills or a tendency to use physical disciplinary methods or accept or justify violence

- poorly controlled psychiatric illness (e.g., psychosis, depression, impulse disorder; (Boos, 2025; CDC, 2024f)

Community risk factors that contribute to child abuse and maltreatment include:

- violence within the community

- neighborhood disadvantages (i.e., high poverty rates, residential instability, high unemployment rates, food insecurity, limited educational/economic opportunities, poor social connections, and easy access to drugs and alcohol)

- communities with low resident involvement, limited activities for young people, or neighbors who do not know/look out for each other (CDC, 2024f)

Protective factors that decrease the risk of child abuse and maltreatment include:

- supportive family environments and social networks

- basic needs met, including housing, food, and safety

- household where the child is monitored and rules are enforced consistently

- readily available parenting skills and child development education

- stability in family relationships

- caregiver higher education and stable employment with family-friendly policies

- caregivers who establish supportive, safe, and positive relationships with their children and use nurturing parenting skills

- access to safe/stable housing, high-quality, affordable preschool/childcare/after-school programs, health care (medical, mental health, and SUD care) and social services (economic/financial help)

- caring adults outside the home who serve as role models or mentors (CDC, 2024f; Daley et al., 2025)

The goal is to prevent abuse and neglect before it happens. Among the preventative techniques is strengthening economic support to families through a family-friendly work policy or household financial security. Social norms and educational campaigns that focus on positive parenting and coaching are effective in promoting healthy behaviors. Children should have quality care and education during their toddler, preschool, and early elementary years. These can be encouraged through state licensing and accreditation of daycare centers and early childhood programs. Initiatives such as early childhood programs and home visits can promote parenting skills and healthy child development (CDC, 2024e).

Children with developmental delays are at increased risk for maltreatment and may be more challenging to assess. This includes those with a history of intellectual developmental delay (previously intellectual disability), autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, seizure disorders (epilepsy), Prader-Willi syndrome, familial dysautonomia, or other underlying causes for neurodevelopmental dysfunction. The indicators for abuse in this population of children may not be as obvious if the child is unable to communicate effectively, requiring the use of nonverbal cues. These include unexplained injuries, a lack of hygiene, malnutrition, severe dehydration, lack of appropriate medical care, and signs of physical restraint (ligature marks). Behavioral indicators include changes in behavior or sleep, loss/regression in skills, self-harming behaviors, agitation or anxiety when in the presence of a particular individual, and inappropriate sexual behavior. A caregiver who is inconsistent, dismissive, excessively angry or frustrated, or socially isolated should also increase the HCP’s concern for potential abuse in a child with developmental delays (PEPR, 2025).

Indicators of Abuse/Maltreatment

Case Study 1: An HCP working in a pediatric emergency department (ED) and is caring for a 4-year-old who has a fractured right arm. They are clinging to their caregiver and crying throughout the assessment. The HCP notices that the child has a long-sleeved shirt on, even though it is the middle of summer. When the HCP rolls back the sleeve, the child has multiple bruises; some are yellow, while others are blue and black. The child’s caregiver notices that the HCP is assessing the child’s arm and begins explaining that the child is "clumsy" and falls all the time. The child looks down when the caregiver talks about their injuries. The HCP asks to take the child to the radiology department for an x-ray, hoping to find time alone with the child. The caregiver refuses to allow the HCP to take the child away, stating that they will go with them.

Considerations: The child has a fractured arm, they have long sleeves on even though it is summertime, and they have bruises in multiple stages of healing. The HCP should initiate a call to the abuse hotline and make a report. Children who are victims of abuse may dress inappropriately to cover injuries, such as wearing long sleeves in the summer. Other signs of abuse in the ED can include caregivers who refuse to leave the child's side, fearing the child may discuss their injuries with the HCP. HCPs should be alert to these situations that indicate the child could be in danger or a victim of abuse (Boos, 2025; Daley et al., 2025; OCFS, n.d.-e). |

Physical Abuse

Physical abuse or bodily injury is a “physical injury by other than accidental means which causes or creates a substantial risk of death, or serious or protracted disfigurement, or protracted impairment of physical or emotional health or protracted loss or impairment of the function of any bodily organ” (New York Family Court Act, 2021, ei). This may also include creating or allowing to create the risk of such a physical injury (New York Family Court Act, 2021, eii). Differentiating between accidental and purposeful physical injuries and abuse can be challenging for HCPs. Indicators of deliberate physical injuries or abuse include:

- human bite marks

- fractures in multiple stages of healing or a history of repeated fractures or certain types of fracture (epiphyseal separations, metaphyseal corner, rib, sternum, scapula, spinous process, vertebral body, long bone in a non-ambulatory infant or bilateral long bones, digital fracture in a child under 36 months old, or skull fracture in a child under 18 months old)

- bedwetting by previously toileting children

- repeated ED visits due to physical injuries

- a caregiver’s report that is inconsistent with the child’s explanation of the injury

- unexplained bruising or injuries on the jaw, cheek, or eye or an area of the body that would not typically be visible through clothing, such as the chest, torso, or buttocks

- bruising of the torso, ears, or neck in a child less than 4 years old, or any bruise in a child under 6 months old

- bruising, burns, or welts with specific shapes such as a belt buckle or handprint, round burns from cigarettes, or marks around the wrist or ankles indicating that the child was restrained and struggling

- multiple bruises or other injuries in various stages of healing

- a non-ambulatory infant with an injury

- injury in a nonverbal child

- mechanism of injury not plausible

- caregiver is unconcerned about the injury

- unexplained delay in seeking care

- injuries to the eyes or both sides of the head or body, as most accidental injuries are unilateral (Boos, 2025; Daley et al., 2025; OCFS, n.d.-e)

Providers should remember that abuse is not always limited to hitting or injuring with associated bruising or visible injuries. Other acts of bodily injury can include burns with hot water, holding a child underwater, throwing objects at a child, physically restraining a child as a form of discipline, and using an object such as a paddle, belt, cord, limb from a tree (switch), or shoe to beat a child. Young children (under age 5) who present to the emergency department (ED) can all be screened for abuse using a validated tool, such as the ESCAPE or P-CAST tool (safe for under age 14), the two-question tool (under age 6), the one-question screen (children under 5), or a complete skin exam by a trained nurse (best for children under age 2). The Hurt Insult Threaten Scream (HITS) tool can also be used to screen pediatric patients for abuse (Boos, 2025; Daley et al., 2025; OCFS, n.d.-e). Behavioral indicators that could suggest abuse or maltreatment include:

- an abrupt change in behavior (e.g., suddenly acting shy or seeking attention)

- a change in school performance, grades, or attendance

- a lack of interest in hobbies/extracurricular activities

- isolating themselves, acting passive, withdrawn, or apathetic

- disruptive, destructive, self-destructive, aggressive, or self-injurious behaviors

- falling asleep during school

- a reluctance to (or fear of) return home after school

- initiating substance use or advancing sexual behaviors (OCFS, n.d.-e; PEPR, 2025)

Case Study 2: A pediatric nurse is admitting a 6-month-old infant. The infant is with their caregiver's significant other since the caregiver is at work. The significant other reports that the infant fell off the bed after they both fell asleep. They further state that "the baby just wanted their parent and cried themselves to sleep." The significant other seems nervous and is texting on their phone in the corner while the nurse assesses the baby. The infant's right pupil is dilated, and they are extremely irritable with a high-pitched cry. The infant is inconsolable with a bottle or pacifier. What should the nurse do next? Considerations: The nuse should first ensure the infant is safe and provide immediate medical attention for potentially devastating or life-threatening brain injuries. The nurse should suspect abusive head trauma (AHT) and initiate a call to the abuse hotline. The nurse should also discuss their concerns with the primary HCP and determine whether the child should be placed in protective custody. It may be necessary to call 911 in this instance for the protection of the child. |

Pediatric AHT

Pediatric AHT results from caregiver abuse and was previously termed shaken baby syndrome. This severe form of child abuse can lead to serious brain injury or death. It often occurs following an infant’s prolonged crying, causing the caregiver to become angry, shake or throw the child down, and ultimately cause a head injury. Bleeding can occur around the brain or on the internal layer of the eyes. Pediatric AHT is a leading cause of abuse-related death in children under 5 years of age in the US, with babies under a year old at the highest risk, and it accounts for more than one-third of all child maltreatment deaths in the US. Long-term consequences of pediatric AHT can include vision problems, developmental delays, physical disabilities, and hearing loss (CDC, 2024b; Christian, 2024). Please see the NursingCE course entitled Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma for more detailed information.

Case Study 3 A nurse is dropping off their young child at school when their first-grade teacher asks to step into their office for advice. The teacher states that the information must be kept confidential, but that they need someone to help make the right decision. The teacher says that one of the children in the class missed 2 days of school last week, then came back to school unable to sit still. The child repeatedly asked to go to the bathroom and seemed uncomfortable sitting. The child has not been able to concentrate and seems distracted during activities they had previously enjoyed. The teacher further noted that the child had extremely chapped lips and reported that their mouth was hurting. The student’s personality had recently changed since one parent started a night shift job, and their other parent is watching them. The student’s caregivers reported that the child is having a hard time transitioning to their new routine. The teacher is worried that the child may be a victim of sexual abuse. The student’s parents are both professionals, and one is a nurse. What must the nurse do? Consideration: The nurse should report if they have any verifiable details or information regarding the child's identity. The teacher is a mandatory reporter, and the nurse should remind the teacher of their responsibility to report this case. |

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse of a child (defined as anyone under the age of 18) is “any interaction between a child and an adult (or another child) in which the child is used for the sexual stimulation of the perpetrator or an observer” (The National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], n.d., para. 1). Sexual abuse is not limited to touching or penetrating the child. It can also include acts intended to arouse the abuser sexually, acts that the child does not comprehend. Other acts considered sexual abuse involve voyeurism (looking at a child’s naked body), exhibitionism (exposing oneself to a minor), and sharing pornographic images, movies, or online materials of children. Children are considered developmentally unable to give their informed consent for sexual activities (CDC, 2024d, NCTSN, n.d.).

A child who is a victim of sexual abuse may exhibit sexual behavior beyond their age or may have a change in toileting habits, such as frequent urination or difficulty with defecation. The child may also have itching, pain, bleeding, or bruising in the genital area. Other symptoms of sexual abuse may include:

- sexually transmitted illnesses (STIs)

- pain, discomfort, or itching in the genital area when trying to sit or walk

- sexual behaviors toward other children

- signs (verbal or physical) of age-inappropriate knowledge of sexual acts or information (Bechtel & Bennett, 2024; OCFS, n.d.-e; PEPR, 2025)

The child may describe sexual actions or act them out, although they are often threatened or intimidated into keeping the activity secret (Bechtel & Bennett, 2024). Behavioral indicators of sexual abuse in children may include regression to earlier developmental stages, such as bedwetting or a refusal/reluctance to change clothes in front of others (e.g., gym class). The child may refuse to participate in sports or otherwise entertaining activities. They may withdraw from friends and family. Other symptoms can include anxiety, anger, depression, promiscuity in older children, internalized symptoms (e.g., upset stomach, headaches), or nondescript symptoms. Some children may not exhibit any indication that they have been sexually abused, making recognition by their HCP more difficult (Daley & Gutovitz, 2025; Schaefer et al., 2018).

Case Study 4 A 12-year-old transgender adolescent is currently in foster care. Their parents threw them out of their home after the adolescent revealed that they are transgender. The adolescent has been in four foster homes and is now having difficulty in school. The adolescent is currently attending their third school in the same year. What are the potential risks for this adolescent? Considerations: The adolescent is at risk for child abuse as well as child sex trafficking. HCPs should provide resources for them, including a referral for mental health services, and discuss these concerns with the primary HCP. |

Child Sex Trafficking

Child sex trafficking is the “advertisement, solicitation, or exploitation of a child through a commercial sex act. A commercial sex act is any sex act where something of value (money, food, drugs, or a place to stay) is given to or received by any person for sexual activity” (National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, [NCMEC] n.d., para. 1). Any child can be targeted for sex trafficking, but the following groups are at increased risk:

- poverty/low socioeconomic status

- young age (12-16 years)

- rural location

- marginalized groups, such as underrepresented racial/ethnic groups, runaway or missing children, migrant workers, individuals with disabilities, or Indigenous People

- children experiencing homelessness

- children who lack a strong support network or formal education

- children with a history of abuse or violence, including sexual abuse, particularly if the child was removed from the home after the event

- children with complex psychiatric conditions or SUD or those who live in a household with persons with SUD

- children identifying as LGBTQ who have been kicked out of their homes (NCMEC, n.d.; Bradley & Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2025)

In 2024, NCMEC received more than 27,000 reports of possible sex trafficking. In addition, the NCMEC has received reports for over 29,000 cases of children who were reported missing, and 1 in 7 of those children were likely victims of child sex trafficking. There are many indicators of sex trafficking in children, but no single indicator confirms that a child is a victim of trafficking. The NCMEC (n.d.) lists several behavioral and physical red flags that HCPs should be aware of when caring for children. Behavioral and physical indicators could include:

- a significant change in behavior, such as increased use of technology or a new group of friends

- a child who allows others to talk for or control them, avoids answering questions when asked, or looks to an unrelated adult when asked a question

- a child who seems scared, resistant, or argumentative or appears coached in responses to law enforcement

- a child who lies about their age or identity, with no ID or an ID in someone else’s possession

- a child who uses terminology that is specific to child trafficking, such as trick, the game, or the life

- access to large amounts of cash or pre-paid credit cards

- a child with bulk sexual paraphernalia such as condoms, lubricants, etc.

- a child with hotel room keys, receipts, or other items from hotels

- a child who refers to traveling to other cities or states, does not typically live in their current location, or cannot recite their existing travel plans or location

- a child who is recovered or found at a truck stop, hotel, or strip club

- a child with items or an appearance that is not congruent with their current situation, such as new clothes, shoes, or expensive electronics

- a child who talks about online classified ads or escort websites

- a child with specific tattoos or burn marks, which are considered branding

- a child with unaddressed medical issues who presents to an ED or clinic without an adult

- a history of substance use, an unusually high number of sexual partners, and/or STIs (NCMEC, n.d.; OCFS, n.d.-d; Bradley & Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2025, Table 2)

The federal Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act was signed into law in 2014 to ensure each “state agency has developed policies and procedures for identifying, documenting in agency records, and determining appropriate services with respect to any child or youth over whom the state agency has responsibility for placement, care, or supervision who the state has reasonable cause to believe is, or is at risk of being, a victim of sex trafficking or a severe form of trafficking in persons” (Title I, Subtitle A). NYS laws reflect the federal focus on decreasing the sex trafficking of children and improving the foster care system, including a Bill of Rights for children in Foster Care.

Case Study 5 Caregiver A is a highly respected nurse educator at a university. They graduated at the top of their class, have a PhD and a DNP, and are often called an "overachiever" by their friends. They have a teenager who is at the top of their class and participates in several sports, excelling at all of them. Today, Caregiver A is bringing their teen to the family practice office for a cough, nasal drainage for 4 days, and a fever. The front desk checks them in and the assistant asks the patient to step on the scale. The patient hesitates, and the caregiver chides them, saying, "get on the scale. You know you have gained weight, so let's see." The patient looks down and steps on the scale, crying silently. The caregiver continues to belittle the patient until their phone rings, and excuses themself while the teen is being examined. When the caregiver leaves the room, the HCP asks the patient if they are ok. The patient says, "I just need to suck it up and accept that I am fat.” The HCP is worried that the teen may be experiencing emotional abuse. What should the HCP do next? Considerations: Attempt to discuss the situation with the teen and allow them to voice their concerns. This family would likely benefit from counseling and mental health services. |

Emotional Abuse

Emotional (or psychological) abuse is a result of a caretaker’s acts or omissions that cause or could cause serious conduct, cognitive, affective, or other mental disorders. This may include the constant use of verbally abusive language, yelling, humiliation, criticism, unrealistic or unreasonable expectations or demands, and unfair treatment. Emotional abuse may also include emotional neglect, which is usually a lack of attention to a child’s emotional needs. Emotional abuse can damage a child’s developing brain. It can lead to long-term learning difficulties, an increased risk of mental health issues, and problematic behaviors or acting out. Emotional abuse can be much more challenging to recognize than other types of abuse, as it can be subtle and seem like a particular parenting style (Kumari, 2020; Prevent Child Abuse America, n.d.). However, the actions constitute abuse if there are ongoing patterns of behaviors that include any of the following:

- rejection of a child wherein the caregiver refuses to recognize the child’s worth and their needs

- isolating or cutting a child off from typical social experiences such as friendships, making the child believe they are alone in the world

- terrorizing a child, creating an atmosphere of fear, or bullying a child and making them feel the world is hostile

- ignoring a child or depriving them of essential stimulation and responsiveness

- corrupting a child or encouraging the child to engage in destructive or antisocial behaviors that are not socially safe or appropriate

- verbally assaulting a child by humiliating them with name-calling, shaming, or sarcasm that injures the child emotionally

- over-pressuring a child or having expectations beyond their ability to achieve (Prevent Child Abuse America, n.d.)

The causes of emotional abuse are multifaceted. A child and their caregiver, community, or society may be involved at several levels. For example, a caregiver could have a mental illness such as depression or SUD, or the child may have a disability such as dyslexia. The caregivers may be upset about the child’s school performance and begin to shame, verbally assault, or respond to them with negativity. Emotional abuse can lead to depression, low self-esteem, separation from family, troubled relationships, or a lack of empathy for others. Emotional abuse can create more lifelong trauma than physical abuse (Prevent Child Abuse America, n.d.).

Case Study 6 A newly graduated nurse working on a pediatrics unit received a report on a 3-year-old child. The patient has been neglected, was removed from the home, and is now living with foster parents. The nurse assumes that neglect means the child was deprived of food, shelter, or basic needs; however, the nurse discovers that this child was taken from their home because the caregivers failed to obtain needed medical services for a brain tumor. Due to their religious beliefs, the caregivers did not obtain medical care for the child, so the state removed the child from the home and mandated treatment for the tumor. The nurse recognizes that they may not fully understand neglect and decides to research the topic online. What other aspects of neglect might the nurse find in this search? Considerations: Neglect can include caregivers who fail to get medical care for their child along with failing to provide the basic needs of food, shelter, or clothing. |

Child Neglect

Child neglect is the “failure of a parent or caretaker to provide needed food, clothing, shelter, medical care, or supervision to the degree that the child’s health, safety, and wellbeing are threatened with harm” (New York City Administration for Children’s Services [NYCACS], n.d., para. 3). This is also referred to as the minimum degree of care. Examples of neglect include:

- a child’s educational needs are not met by either failing to enroll the child in school, keeping the child at home during school time for unexcused reasons, or failing to follow up with a child’s educational needs after school outreach to the caregiver

- adequate clothing, food, or shelter is not provided

- adequate medical or mental healthcare is not provided, including dental care and treatment for SUD

- adequate supervision is not provided, such as being left home alone without the knowledge and skills necessary to respond to a potential emergency properly and to care for themselves

- a child is subjected to fear, verbal terror, extreme criticism, or humiliation

- a child receives excessive corporal punishment to the point of physical or emotional harm, the child cannot understand the corrective nature of the discipline, a less severe method is available and effective, or the duration surpasses the child’s endurance

- a child is exposed to family violence

- a child is in the presence of keeping, manufacturing, or selling drugs or is given drugs by a caregiver

- a caregiver who is unable to care for the child due to the effects of SUD (Daley et al., 2025; Harper & Foell, 2023; NYCACS, n.d.)

Signs of each type of neglect will be unique. For example, if a child does not have adequate food, they may be severely underweight for their age and height. It is not uncommon for multiple types of neglect to occur simultaneously. Some general signs of child neglect are as follows:

- inappropriate growth for age (e.g., lags in physical development or growth)

- malnourishment or weight gain/elevated BMI

- poor hygiene (dirty hair, skin, or body odor)

- inappropriate clothing or a lack of clothing and supplies for physical needs

- extreme fatigue or falling asleep in class

- demanding constant attention or affection in school or elsewhere

- hiding food for later or to bring to siblings

- taking food or money without permission

- a lack of appropriate dental, medical, or mental health care or failing to follow up

- a lack of supervision appropriate for the child’s age and development (Daley et al., 2025; Harper & Foell, 2023; OCFS, n.d.-e; PEPR, 2025)

SUD in a caregiver often contributes to the neglect or abuse of children. For example, a child may accidentally ingest drugs, or their caregiver may be too impaired to care for the child, leading to neglect. Additionally, older children are sometimes responsible for younger siblings and may not be able to provide adequate care. Therefore, HCPs should be aware of the possibility of neglect and respond appropriately (Harper & Foell, 2023; NYCACS, n.d.). Educational neglect is characterized by excessive absences in a school-aged child without a valid reason. However, absenteeism alone is not typically a sufficient reason to warrant a report to the SCR. The absences must be affecting the child’s education or their ability to obtain needed services (if the child has an individualized education program or IEP), and the caregiver must be aware of the absences and their effect. School officials must first make sufficient efforts to engage with the family and devise a solution (OCFS, n.d.-e; PEPR, 2025).

Case Study 7 A 28-year-old single parent whose significant other comes in and out of their life brings their 2-year-old child into the clinic stating that the child had a temperature of 103 °F throughout the night. The significant other is also the co-parent of the child. Today, the toddler is afebrile. They further report that the child had blood in their urine a few days prior. The nurse obtains a urine specimen that is clear. The nurse sees throughout the child’s medical record that they are frequently brought to the office by their caregivers; many tests have been run on the child, most of which are negative. The provider decides to admit the child for observation and obtain further labs. The nurse takes a cup to the parent and asks them to get a urine specimen the next time they take the child to the restroom. After leaving the room, the nurse hears the patient crying and goes in to find the parent trying to stick the child with a needle; the urine cup is open with a specimen on the bedside table. What should the nurse do? Considerations: This child may be a victim of medical child abuse (MCA). The nurse should vocalize their concerns to the primary HCP and question the parent about these events. |

Medical Child Abuse (MCA)

Medical child abuse (MCA) is abuse involving an intentional production of illness (or the exaggeration or fabrication of symptoms) in a child to assume the sick role by proxy. The proxy is usually a parent/caregiver who intentionally makes a child ill or fabricates symptoms to gain attention. The diagnosis and treatment of this health disorder are complicated. Victims are typically under 6 years of age, and the cases are usually undiagnosed; MCA wastes medical services and can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in children. Unnecessary diagnostic tests or harmful (or potentially harmful) treatments are performed due to fabricated symptoms. MCA perpetrators have different motives, including attention-seeking, manipulation, satisfaction from deceiving others, or gaining a sense of control. The prognosis for the child depends on the severity of the damage done by the abuser. The term factitious disorder imposed on another (FDIA, previously Munchausen syndrome by proxy) is used to describe the psychiatric condition that applies to a perpetrator of MCA (American Academy of Family Physicians [AAFP], 2024; Roesler & Jenny, 2024).

A perpetrator may purposely make the child sick by withholding food, poisoning or suffocating the child, giving inappropriate medications, or withholding prescribed medications. The caregiver may knowingly expose the child to risky and painful medical procedures, including surgery (AAFP, 2024; Roesler & Jenny, 2024). Some common illnesses that caregivers seek medical help for MCA victims can include:

- nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea

- failure to thrive

- seizures

- infections

- fevers of unknown origin

- allergic reactions

- breathing difficulties (AAFP, 2024; Roesler & Jenny, 2024)

Mandatory Reporting

In New York, OCFS, local CPS agencies, the SCR, and mandated reporters work cooperatively to promote the wellbeing of children, families, and communities in New York. HCPs should be thoroughly familiar with the policies and procedures in their workplace, as well as applicable state laws. In NYS, these laws direct the handling of suspected child abuse or maltreatment. If an organization’s policies and procedures are not aligned with state laws and directives, HCPs are still obligated to follow the law. HCPs must report suspected child abuse and maltreatment immediately and are considered mandated reporters. Mandated reporters can include the following (refer to the OCFS website for the full list):

- medical and hospital personnel, including nurses, physicians, therapists, etc.

- school officials

- social service workers

- childcare workers

- residential care workers and volunteers

- law enforcement personnel (OCFS, 2024)

The NYS OCFS maintains the SCR, also known as the “hotline” for reporting suspected or confirmed abuse and maltreatment according to the Social Services Law (800-635-1522; OCFS, n.d.-f). This hotline is available 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. The SCR will conduct a brief interview to determine if the concerns meet the legal criteria for suspected child abuse and whether or not the report can be accepted based on this information. After a report is accepted, local CPS is contacted to initiate an investigation within 24 hours and determine whether there is a history of child abuse or maltreatment reports. The reporter must complete and sign a written report (Local Department of Social Services [LDSS] Form 2221A) within 48 hours of the initial phone call to the hotline. The form can be found on the OCFS website and must be mailed to the local CPS office address on the site. The form must include:

- full name, address, and date of birth (if available) of the child’s legal guardian/caregiver/PLR

- full name, address, and date of birth (if available) of the child

- specific information that led to the reasonable suspicion of abuse

- the HCP/mandatory reporter’s full name, contact information (including email and phone), and name of agency/organization

- any other mandated reporters who observed/have information on the child

The form should include a list of all children in the household, the basis of suspicion, any medical examination information, photographs, radiographs, or any images obtained during the child’s assessment. Any information from the child or caregiver should be explicitly stated and accurately quoted. Appropriate medical care should be provided during the visit and documented in the report. HCPs are not required to notify caregivers before or after submitting a report to SCR. Often, alerting caregivers could jeopardize the child’s welfare and hinder the investigation (OCFS, 2021a; PEPR 2025).

The caseworker will contact the PLR, the source of the report, and request copies of pertinent records or reports. The caseworker may also take the child into protective custody if the child is in danger. CPS has 60 days to perform an investigation and determine whether the report is indicated or unfounded. The written report may become part of future court proceedings and should be thoroughly completed (OCFS, 2021a).

Mandated reporters must report suspected abuse when, in their professional role, they interact with a patient under the age of 18 who presents a reasonable cause to suspect abuse or maltreatment by a PLR for their care at the time (custodian, guardian, parent, or any adult regularly in the same household). HCPs who are on duty are required to report any suspicion of abuse. If an HCP is off duty and suspects child abuse while not in their professional capacity, they are not legally obligated to report it in New York but still have a moral obligation to report it. Reasonable cause is based on the HCP’s professional training and experience, observation, or suspicions that imminent danger of harm by a caregiver to a child exists (PEPR, 2025). The standards for making a report per the Social Services Law - SOS § 413 are as follows:

“Persons and officials required to report cases of suspected child abuse or maltreatment:

- when they have reasonable cause to suspect that a child coming before them in their professional or official capacity is an abused or maltreated child; or

- when they have reasonable cause to suspect that a child is an abused or maltreated child where the parent, guardian, custodian, or another PLR for the child comes before them in their professional or official capacity and states from personal knowledge facts, conditions, or circumstances that, if correct, would render the child an abused or maltreated child” (New York Child Protective Services, 2024, subsection 1).

Failure to report suspected abuse could result in severe consequences for the child. Thus, HCPs who fail to report suspected child abuse are at risk of a Class A misdemeanor, are subject to criminal penalties, and can be sued in civil court for monetary damages that may arise from harm caused by the failure to report to the SCR (OCFS, 2021a; PEPR, 2025).

Legal Protections for Mandatory Reporting

NYS law protects HCPs and provides immunity from liability for mandated reporting. The Social Services Law assures confidentiality for mandated reporters and all sources of maltreatment or abuse reports. Reports and all associated information may be shared with police, court officials, and district attorneys under certain circumstances. When reports are made in good faith, out of sincere concern for the child’s wellbeing, the reporter is immune from criminal or civil liability. Section 413 of the NY Child Protective Services Law specifies that “no medical or other public or private institution, school, facility, or agency shall take any retaliatory personnel action against an employee who made a report to the SCR”. Health care organizations are not permitted to prevent reports from being made by employees or to require permission prior to an employee filing a report (New York Child Protective Services, 2024, subsection 1; PEPR, 2025).

Strategies to Reduce Implicit Bias

HCPs are responsible for identifying the signs and symptoms of child abuse and maltreatment and have a duty to report any suspicion of abuse or maltreatment immediately. Healthcare organizations must ensure that standardized protocols and guidelines are in place to ensure the care provided in these situations is delivered fairly and equitably to all patients regardless of age, gender, race, ethnicity, religious or cultural background, sexual identity, or physical disability. Although some biases are conscious (explicit), implicit bias refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that unconsciously affect our actions, understanding, and decisions. These biases can include favorable and unfavorable assessments of another person and are activated involuntarily without individual awareness or intentional control. The decision to report suspected child abuse and maltreatment can be difficult for HCPs to make, and implicit bias can occur, resulting in inequity based on socioeconomic status, race, gender/sex, and numerous other factors. Overreporting of child abuse and maltreatment occurs for families of lower socioeconomic status, while underreporting occurs with families of higher socioeconomic status. Numerous individual and community factors contribute to the risk of child abuse and maltreatment. HCPs may interpret social risk factors and apply them in ways that perpetuate bias. Families of color are more likely to have CPS cases opened, and children of color are at greater risk of being placed out of the home. Strategies to reduce implicit bias include universally implementing validated screening tools, clinical guidelines, and electronic health record alerts to support clinical decision-making regarding child abuse and maltreatment. HCPs should participate in effective and comprehensive implicit bias training on a regular and ongoing basis. Building diverse, multidisciplinary teams can also minimize bias in medical decision-making. Being aware of the biases HCPs hold and how they may impact decision-making is the first step in reducing their effect. Critical thinking is a proven tool to reduce bias. HCPs should openly and consistently consider if their decision to file a report would be different if the race/ethnicity, age, religion, immigration status, sex assigned at birth, gender identity/expression, sexual orientation, primary spoken language, culture, neighborhood, disability, socioeconomic status, or occupation of the patient or their caregiver were different (Letson & Crichton, 2023; PEPR, 2025; Palusci & Botash, 2021). Project Implicit has developed the Implicit Association Test (IAT) in collaboration with several major universities and made it available free of charge for adults over the age of 17 (Project Implicit, n.d.).

Trauma-Informed Care (TIC)

The Center for Health Care Strategies (n.d.) describes TIC as shifting the focus from what is wrong with the survivor to what happened to the survivor. They further explain that healthcare organizations and teams must develop a complete picture of a patient’s past and present life situation to care for the entire patient with a healing orientation. The HCP must recognize the impact that trauma has had on the patients and families that they care for. If implemented optimally, TIC can improve patient outcomes, enhance treatment adherence, reduce healthcare and social services costs, and promote the wellness of HCPs and staff. It must be adopted at both the clinical and organizational levels. TIC seeks to:

- realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand paths for recovery

- recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, and staff

- integrate knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices

- actively avoid retraumatization (Center for Health Care Strategies, n.d., para. 2)

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2014) defines TIC as including the four Rs (Table 1):

Table 1

The Four Rs of TIC

Realize |

Recognize |

Respond |

Resist retraumatization |

(SAMHSA, 2014)

The four Rs approach, if applied consistently, will create a trauma-informed culture and organization that meets the needs of abuse survivors (SAMHSA, 2014).

Resources for Families

A referral to CPS is not the only way to support a family in need. The OCFS (n.d.-c) provides a hotline for parents and families to access community services. The Help, Empower, Advocate, Reassure, and Support (HEARS) line can be reached by calling (888-55HEARS or 888-554-3277) on weekdays from 8:30 to 4:30. This hotline can connect community members with food, housing, clothing, health care (both medical and behavioral), child care, and caregiving education. Information is available in 12 languages (OCFS, n.d.-c). The OCFS website (ocfs.ny.gov) offers extensive resources for HCPs, caregivers, and families on ACEs and local resources available (OCFS, n.d.-a). The New York State Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violence (OPDV) maintains a confidential support line 24 hours a day (call 800-942-6906 or text 844-997-2121) as well as a website with various educational and community resources for survivors of sexual or intimate partner violence, including legal advocacy, counseling, housing, information, and emotional support (OPDV, n.d.). The National Childhelp hotline (800-422-4453) is a similar confidential helpline offering help and resources from trained counselors 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (HHS, n.d.).

Conclusion

Adverse experiences in childhood impact not only the child’s mental and physical development but also future violence victimization and perpetration. In addition, abuse and maltreatment affect a child’s lifelong mental and physical health and opportunities. HCPs can protect children from further harm through early intervention and identification, allowing entire families to live with safe, stable, and nurturing relationships that extend to future generations (CDC, 2021).

References

Administration for Children and Families. (2025). Child maltreatment 2023. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/cm2023.pdf

American Academy of Family Physicians. (2024). Munchausen syndrome by proxy. https://familydoctor.org/condition/munchausen-syndrome-proxy

Bechtel, K., & Bennett, B. L. (2024). Evaluation of sexual abuse in children and adolescents. UpToDate. Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-sexual-abuse-in-children-and-adolescents

Boos, S. C. (2025). Physical child abuse: Recognition. UpToDate. Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/physical-child-abuse-recognition

Bradley, E. T., & Macias-Konstantopoulos, W. L. (2024). Human trafficking: Identification and evaluation in the health care setting. UpToDate. Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/human-trafficking-identification-and-evaluation-in-the-health-care-setting

The Center for Health Care Strategies. (n.d.) What is trauma-informed care? Retrieved June 4, 2025, from https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org/what-is-trauma-informed-care/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Violence prevention: About the CDC-Kaiser ACE study. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): About adverse childhood experiences. https://www.cdc.gov/aces/about/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024b). Child abuse and neglect prevention: About abusive head trauma. https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/about/about-abusive-head-trauma.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024c). Child abuse and neglect prevention: About child abuse and neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/about/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024d). Child abuse and neglect prevention: About child sexual abuse. https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/about/about-child-sexual-abuse.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024e). Child abuse and neglect prevention: Preventing child abuse and neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024f). Child abuse and neglect prevention: Risk and protective factors. https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/risk-factors/

Christian, C. (2024). Child abuse: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and types of abusive head trauma in infants and children. UpToDate. Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/child-abuse-epidemiology-mechanisms-and-types-of-abusive-head-trauma-in-infants-and-children

Congress.gov. (n.d.). Constitution of the United States: Fourteenth Amendment. Retrieved December 13, 2023, from https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-14

Daley, S. F, Gonzalez, D., Bethancourt Mirabal, A., & Afzal, M. (2025). Child abuse and neglect. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459146

Daley, S. F. & Gutovitz, S. (2025). Child sexual abuse. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470563

di Giacomo, E., Santorelli, M., Pessina, R., Rucco, D., Placenti, V., Aliberti, F., Colmegna, F., & Clerici, M. (2021). Child abuse and psychopathy: Interplay, gender differences, and biological correlates. World Journal of Psychiatry, 11(12), 1167-1176. https://doi.org/10.5498%2Fwjp.v11.i12.1167

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 746-754. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676

Jones, C. M., Merrick, M. T., & Houry, D. E. (2020). Identifying and preventing adverse childhood experiences. JAMA, 323(1), 25-26. https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjama.2019.18499

Joyce, T., Gossman, W., & Huecker, M. R. (2023). Pediatric abusive head trauma.

StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499836

Kumari V. (2020). Emotional abuse and neglect: Time to focus on prevention and mental health consequences. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 217(5), 597–599. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.154

Letson, M. M., & Crichton, K. G. (2023). How should clinicians minimize bias when responding to suspicions about child abuse? AMA Journal of Ethics, 25(2), E93-E99. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2023.93

Lippard, E. T. C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2020). The devastating clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect: Increased disease vulnerability and poor treatment response in mood disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(1), 20-36. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010020

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. (n.d.). Child sex trafficking. Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://www.missingkids.org/theissues/trafficking

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). Sexual abuse. Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/sexual-abuse

New York Child Protective Services, Title 6. (2014). https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/SOS/A6T6

New York Child Protective Services, General definitions. NY Stat. § 412. (2022). https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/SOS/412

New York Child Protective Services, Persons and officials required to report cases of suspected child abuse or maltreatment. NY Stat. § 413. (2024). https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/SOS/413

New York City Administration for Children’s Services. (n.d.). What is child abuse/neglect? Retrieved June 5, 2025, from https://www1.nyc.gov/site/acs/child-welfare/what-is-child-abuse-neglect.page

New York Family Court Act, NY Stat. § 1012. (2021). https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/FCT/1012

New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. (2022). About the NYSPCC. https://nyspcc.org/about-nyspcc/history

New York State Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violance (n.d.). Survivors and victims. Retrieved June 4, 2025 from https://opdv.ny.gov/survivors-victims

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (n.d.-a). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Retrieved June 4, 2025 from https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/cwcs/aces.php

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (n.d.-b). Definitions of child abuse and maltreatment. Retrieved December 13, 2023, from https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/cps/critical.asp

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (n.d.-c). HEARS family line. Retrieved June 4, 2025 from https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/cwcs/hears.php

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (n.d.-d). Red flags of CSEC and child trafficking. Retrieved June 4, 2025, from https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/human-trafficking/assets/docs/red-flags-of-CSEC-and-child-trafficking.pdf

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (n.d.-e). Signs of child abuse or maltreatment. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/cps/signs.php

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (n.d.-f). The statewide central register of child abuse and maltreatment. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/cps

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (2015). Informational letter regarding the preventing sex trafficking and strengthening families act (PL 113-183). https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/OCFS_2015/INFs/15-OCFS-INF-03%20%20Preventing%20Sex%20Trafficking%20and%20Strengthening%20Families%20Act%20(P.L.%20113-183).pdf

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (2023). 2022 child fatality report. https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/2022-Child-Fatality-Report.pdf

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (2024). Summary guide for mandated reporters in New York State. https://www.ocfs.ny.gov/publications/Pub1159/OCFS-Pub1159.pdf

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (2025). Child protective services (CPS) reports data packet 2020-2024. Retrieved June 9, 2025 from https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/ocfs.nys/viz/CPSReports4/Home

North Central Missouri Children’s Advocacy Center. (2020). Child abuse resource for the North Central Missouri area. https://www.ncmochildren.org/ncmcac/2020/12/recognizing-child-abuse-and-neglect-in-telehealth-care.html

Palusci, V. J., & Botash, A. S. (2021). Race and bias in child maltreatment diagnosis and reporting. Pediatrics, 148(1), e2020049625. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-049625

Prevent Child Abuse America. (n.d.). Fact sheet: Emotional child abuse. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from http://preventchildabuse.org/images/docs/emotionalchildabuse.pdf

Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act, Pub. L. No. 113-183. (2014). https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/

Professional Education Program Review. (2025). Amended mandated reporter syllabus. New York State Education Department.

Project Implicit. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved June 4, 2025, from https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/aboutus.html

Roesler, T. A., & Jenny, C. (2024). Medical child abuse (Munchausen syndrome by proxy). UpToDate. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/medical-child-abuse-munchausen-syndrome-by-proxy

Schaefer, L. S., Brunnet, A. E., de Oliveira Meneguelo Lobo, B., Castro Nunez Carvalho, J., & Kristensen, C. H. (2018). Psychological and behavioral indicators in the forensic assessment of child sexual abuse. Trends in Psychology, 26(3), 1483-1498. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2018.3-12En

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. https://youth.gov/feature-article/samhsas-concept-trauma-and-guidance-trauma-informed-approach

US Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). The childhelp national child abuse hotline. Retrieved June 4, 2025 from https://www.childhelphotline.org/

US Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). The childhelp national child abuse hotline. Retrieved June 4, 2025 from https://www.childhelphotline.org/

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act: 40 years of safeguarding America’s children. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/capta_40yrs.pdf

Powered by Froala Editor