About this course:

This learning activity aims to increase the learner's knowledge of the background, transmission, diagnosis, staging, treatment, and prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Course preview

Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

This learning activity aims to increase the learner's knowledge of the background, transmission, diagnosis, staging, treatment, and prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

This learning activity is designed to allow the learner to:

- define HIV and AIDS and understand the impact in the United States and globally

- discuss the stages of HIV

- explain HIV testing and patient counseling

- identify the factors that affect transmission and methods to decrease the risk of HIV infection

- consider occupational exposures to bloodborne pathogens and the risks to healthcare providers (HCPs)

- summarize the clinical manifestations and treatment of HIV and AIDS

Background

A diagnosis of HIV infection or AIDS was considered a death sentence just four decades ago when the disease emerged in the United States and worldwide, but current prognosis and outcomes have significantly improved due to advances in treatments. It is now considered a manageable chronic disease, with a life expectancy almost equivalent to people without HIV. Although data shows that HIV started infecting humans in the 1950s, scientists were unaware of the virus until decades later. Beginning in the early 1980s, unusual illnesses were emerging throughout the world. Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), a reasonably harmless cancer previously common among older adults, started appearing as an aggressive strain in younger patients. At the same time, rare and aggressive types of pneumonia also began appearing in young patients. By 1981, scientists began to connect these two new diagnoses with the emergence of other opportunistic infections. By the end of 1981, the first case of AIDS was documented in the medical literature as a "cellular-immune dysfunction related to a common exposure," with 337 cases reported in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2001, para. 1). Of those, 130 died by the end of December 1981. The terminology acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) was first used by the CDC in September of 1982 (CDC, 2001; Melhuish & Lewthwaite, 2022; US Department of Health & Human Services [HHS], n.d., 2024a, 2025d).

Scientists aggressively worked to figure out the poorly understood new deadly disease. In the early years, all that was known about HIV was that it was viral, fatal, and highly contagious. Fear from both HCPs and the public fueled prejudice and discrimination against those thought to be at the highest risk of contracting the virus. It was noted early in 1981 that many people diagnosed with HIV were young men who have sex with men (MSM); therefore, it was assumed that the virus was likely sexually transmitted. Consequently, HIV was labeled as a homosexual-related illness, immediately stigmatizing the diagnosis. However, other early events, such as the AIDS outbreak in Haiti, the identification of those who used certain illicit drugs patients with hemophilia as at-risk populations, and mother-child transmission in utero, inspired doctors and scientists to focus on bloodborne and maternal transmissions in addition to sexual transmission. The stigmatization, however, persisted. HIV patients were ostracized due to mass hysteria, including a young student with a history of hemophilia who was HIV positive, Ryan White, who was expelled from his middle school in Indiana in 1985. He became a poster child of the crisis and advocate for people who had AIDS, inspiring the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act (HHS, n.d.).

Public policy responded by closing nightclubs and bathhouses that catered to a clientele of gay adults. Law enforcement officers were issued masks and gloves to protect them from exposure to the virus, and needle exchange programs began to address the concerning trend of reusing needles among drug users. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) started to consider the safety of the nation's blood bank after a postpartum patient was diagnosed with AIDS just months after giving birth and receiving subsequent blood transfusions. In 1985, the first International AIDS meeting was held, sparked by the appearance of the disease across the globe. In 1986, a chemotherapeutic agent, zidovudine (Retrovir, AZT), became the first antiretroviral therapy (ART) after highly effective clinical trials in the United States. The trials were halted early because it was considered unethical to give infected patients a placebo instead of the true medication (HHS, n.d.).

The crisis escalated quickly, and by 1993 there were more than 2.5 million cases of HIV worldwide. By 1995, HIV had become the number one cause of death for Americans between the ages of 25 and 44. In 1996, the United Nations (UN) reported more than 3 million new cases worldwide in patients under age 25. The mortality rate did not improve until 1997. During this time, legislation was passed in the United States prohibiting HIV-positive individuals from working in health care settings, donating blood, entering the country on a travel visa, or immigrating to the United States. Meanwhile, new drugs were being studied, including saquinavir (Invirase) and nevirapine (Viramune). Combination therapy approaches demonstrated success, and by 1997 a global HIV treatment guideline for ART was established. Prevention techniques were also identified, including condom use. The condom was rarely discussed before the HIV era, yet its use became a mainstay for HIV prevention. President Bill Clinton aggressively advocated for HIV/AIDS education and allocated many resources toward HIV/AIDS research during his eight years in office. Additionally, the World Health Organization (WHO) AIDS program was created and later replaced by the current joint UNAIDS Global Programme (HHS, n.d., 2021).

It was not until 2010 that the United States removed HIV as an infection that prevented non-US citizens from entering the country. In 2010, researchers discovered that ART drugs used to treat HIV could also be taken prophylactically to prevent infection in individuals at increased risk of exposure through sex. This is known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and its use was eventually expanded to include more individuals at increased risk of exposure. Also, new data showed that actively treating HIV reduced transmission by 96%. From 2010 to 2020, numerous campaigns were launched to get more individuals tested and reduce the stigma surrounding HIV. Despite the forward movement, in 2019 the CDC reported stalled progress in reducing HIV cases in the United States and recommended increased testing. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States (NHAS) was started during the Obama administration in 2010 and Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) was formed by President Trump in 2019, both created with the aggressive goal to end HIV in the United States by 2030. With the CDC, the NHAS and EHE work collaboratively toward a current revised goal of a 90% reduction in new HIV infections by 2030 (CDC, 2025f; Crowley, 2010; HHS, n.d., 2025c).

Pathophysiology

HIV is a retrovirus that attacks and depletes the human immune system and limits the body's ability to protect against disease and infections. The former healthy immune system of the affected individual is also unable to stop the progression of HIV. HIV targets CD4+ lymphocytes, also known as T-cells or T-lymphocytes. T-cells work with B-lymphocytes as part of the acquired (adaptive) immune system. HIV integrates its RNA into the host cell's DNA through reverse transcriptase,...

...purchase below to continue the course

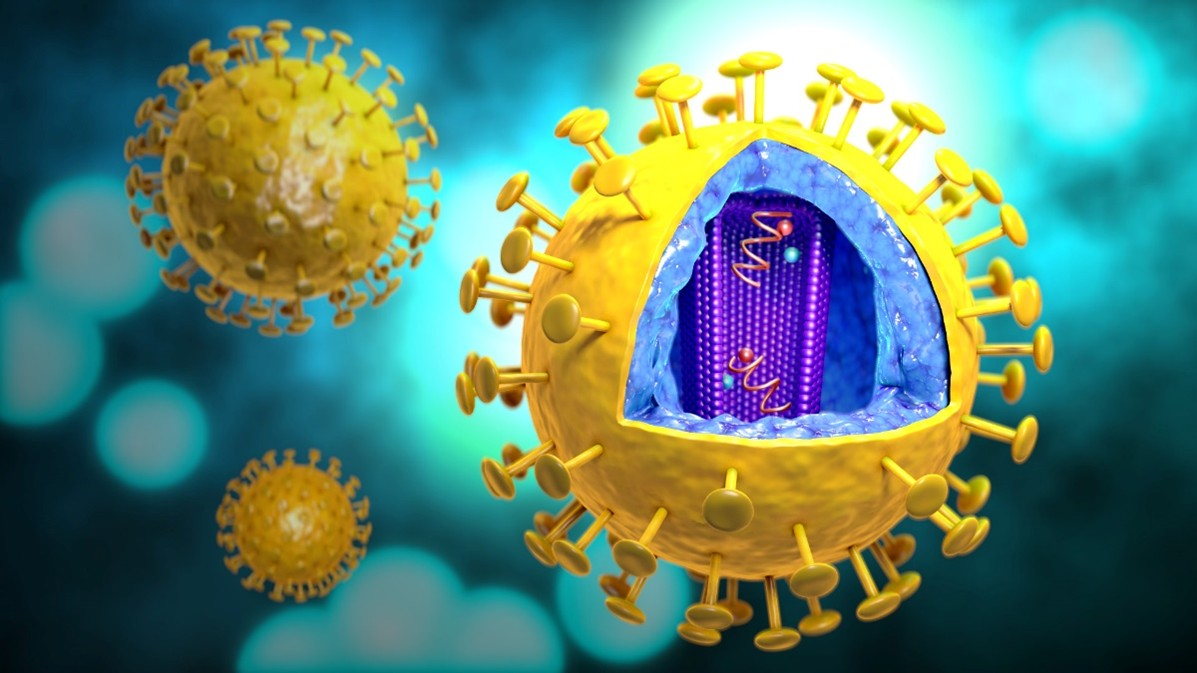

Figure 1

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

(CDC, 2024c)

Strains of HIV

HIV is classified into types, groups, and subtypes. There are multiple strains of HIV due to the high variability of the virus and its mutational capabilities. The two primary strains are HIV-1 and HIV-2. The predominant strain worldwide is HIV-1, whereas HIV-2 is less common and found predominantly in West Africa. Both strains can progress to AIDS and are transmitted through blood and bodily fluids. Each strain has several subtypes and is evolving continuously. HIV testing detects the two primary strains and all known subtypes (Arcangelo et al., 2022; Peruski et al., 2020; Swinkels et al., 2024).

Incidence and Prevalence

The WHO estimates that HIV has claimed 42.3 million lives to date. In 2023, 39.9 million people were living with HIV or AIDS. Of this estimated total, 86% had a diagnosis, 77% were receiving ART, and 72% had suppressed viral loads. The UN's goal for 2025 was to raise all those percentages to 95%, but statistics from 2024 were not on track to meet this target. It was estimated in 2023 that 65% of people living with HIV reside in the African region. The same year, there were also approximately 1.3 million new cases of HIV and 630,000 deaths due to an HIV-related illness. The distribution of these cases by sex was 720,000 in those assigned male at birth and 580,000 in those assigned female at birth (Swinkels et al., 2024; WHO, n.d., 2024b, 2024c, 2024d).

In the United States, approximately 1.2 million people are living with HIV. In 2022, there were 31,800 new cases of HIV diagnosed in the United States, a 12% decline from 2018. Overall, there has been over a 75% reduction in HIV diagnoses since the mid-1980s. New diagnoses are not spread evenly throughout patient demographics. Almost half of the new cases in 2022 occurred in the southern United States. New cases of HIV in 2022 were more likely to affect individuals aged 13 to 34 (56%), followed by those aged 25 to 34 (37%). Distribution by ethnicity among new cases in 2022 was Black/African American (37%), followed by Hispanic (33%), and White (24%). The 2022 statistics confirmed that there continues to be a wide disparity in distribution by sex: 81% occur in those assigned male at birth, which is four times the infection rate of 19% in those assigned female at birth. Gay, bisexual, and other MSM remain the population most affected by HIV in the United States, accounting for 67% of new cases and 83% of all cases in 2022 (CDC, 2021a; HHS, 2025d).

Transmission and Infection Control Guidelines

Viral Load

Viral load refers to the amount of virus detected in a blood sample. The viral load influences the transmission of the virus and is the primary indicator of response to ART. For transmission to occur, there must be enough of the virus present in the affected individual. This is referred to as a sufficient dose. A high viral load indicates that the immune system is not effectively fighting the virus, and the individual is more infectious to others. Conversely, a low viral load is associated with a low transmission rate to sexual contacts. The global effort, Prevention Access Campaign "U=U," was launched in 2016 when it was recognized that an undetectable amount of HIV correlates with a lack of transmission of HIV infection. This concept of "U=U" stands for undetectable equals untransmittable. This campaign aims to make people aware that compliance with ART can lead to an undetectable viral load, indicating that the patient will not transmit the disease to others (CDC, 2024j; Hollier, 2021; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Swinkels et al., 2024).

Modes of Transmission

For transmission to occur, HIV must enter an individual's bloodstream. It is not passed through casual contact from person to person (skin to skin). For an individual to become infected with HIV, the following conditions must be met:

- an HIV source

- enough virus present; high viral load in the affected individual

- contact with the affected individual's blood or specific bodily fluids (CDC, 2024e)

Without these conditions, HIV cannot spread. HIV is transmitted through blood and body fluids, such as semen, pre-seminal fluid, vaginal secretions, and breast milk. It is not transmitted through saliva, tears, or sweat. In the United States, HIV is mainly spread by unprotected anal or vaginal sex with an individual infected with HIV who is not taking prophylactic medications. For an HIV-negative partner, receptive anal is the highest-risk sexual behavior, but HIV can also be acquired from penetrative anal sex. During vaginal sex, either partner can contract HIV, though it is less risky than anal sex. The CDC reports that all forms of oral sex have a low risk of transmitting HIV. Still, it is possible to transmit during oral sex if an HIV-positive individual ejaculates in their partner's mouth with breaks in the gums or mucosa. Sharing needles or syringes with someone who is HIV-positive is also high-risk behavior. HIV can live in a used needle for up to 42 days, based on storage conditions. Perinatal transmission (during pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding) is how most children become infected with HIV (CDC, 2024e).

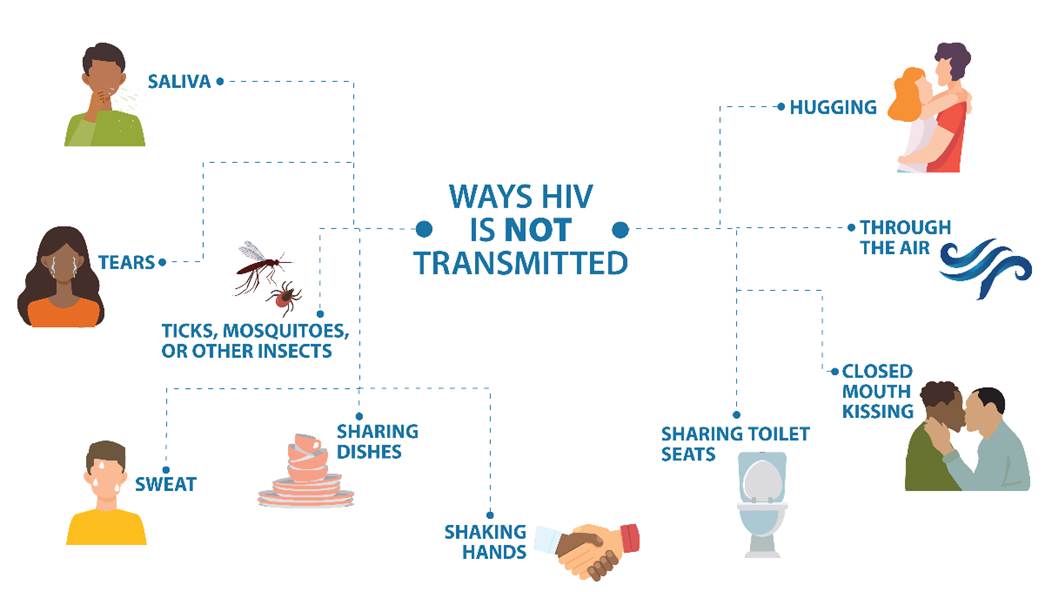

Aside from blood in used needles, HIV cannot reproduce or survive long outside the human body. Therefore, HIV cannot be spread by vectors such as mosquitoes or ticks. Handling leftover food, exposure to saliva, or being scratched by an HIV-positive individual cannot cause HIV infection. Tattoo or body piercing equipment can cause an HIV infection, but the risk is low and is directly related to unsanitary practices such as reusing piercing and tattoo needles (CDC, 2024e). Refer to Figure 2 for common HIV transmission myths.

Figure 2

HIV Transmission Myths

(CDC, 2024e)

Social Factors that Influence HIV Transmission

Other factors affecting transmission include infection with other sexually transmitted illnesses (STIs), substance use, lack of circumcision, and imbalance of power in relationships. Less common transmission causes include bites and workplace exposure. STIs increase the risk of infection with HIV due to skin and mucous membrane compromise that allows HIV easier access to the body. Symptomatic herpes and syphilis can cause a break in skin integrity from blisters and sores. Chlamydia causes inflammation, which can increase HIV viral shedding and the viral load in genital secretions. Any genital ulcers, wounds, or inflamed tissues can become an easy entry point for HIV, and thus increase the risk of exposure (CDC, 2024e; Cohen, 2025).

Substance use increases the risk of HIV exposure in more than one way. In addition to exposure through shared needles, impaired judgment from the use of alcohol and other substances also increases the risk. While under the influence of drugs or alcohol, an individual is more likely to participate in risky behavior due to impaired judgment, leading to an increased risk of infection. Also, substances can alter the pain response and lead to unnoticed sores or open wounds in the mouth or genital area, which increases the risk of HIV infection and other STIs (CDC, 2024e).

Domestic violence and cultural implications can create an environment that puts one of the partners in the relationship at risk. For instance, in some cultures, people who are assigned female at birth are not allowed to question their partners and are expected to follow strict rules and restrictions related to sexual activity. They may be unable to request the use of protection during intercourse, which places them at increased risk of infection. All people who are victims of domestic abuse and sexual abuse may be unable to discuss their sexual history or safe sex practices. This problem can exist in all types of relationships, regardless of sexuality or gender. Other issues of inequality that could lead to HIV transmission include substantial differences in age or wealth. In any situation where one partner has power or control over another, the likelihood of protection, honesty/transparency, and safe sex practices decreases, and the possibility of exposure to HIV or other STIs increases (CDC, 2024e; Fauk et al., 2021).

Human bites rarely lead to the transmission of HIV; however, if someone has bleeding gums or open sores in their mouth, there is a small risk of exposure. Other diseases can be more easily transmitted via a human bite, so care should be taken to cleanse the bite wound immediately with soap and water. Antibiotic prophylaxis may be indicated (CDC, 2024e).

Infection Control Practices in the Workplace

Each health care organization should have a bloodborne pathogen policy and procedures that protect employees from exposure to blood and potentially infectious bodily fluids. HCPs are at higher risk of exposure to blood and bodily fluids during routine patient care. In addition to HCPs, first responders, law enforcement, and public service employees are at increased risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens such as the hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and HIV in their work roles. Each employer is responsible for training employees on the risk of bloodborne pathogens and providing the equipment to protect them from exposure, including proper personal protective equipment (PPE). Exposure types include occupational exposure and exposure incidents (CDC, 2024d; Hollier, 2021; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], n.d.).

Occupational exposure is the exposure of the skin, eyes, mucous membrane, or bloodstream to blood or other potentially infectious material (OPIM) that results while an employee performs their routine duties. An exposure incident is a specific eye, mouth, mucous membrane, non-intact skin, or parenteral contact with blood or OPIM resulting from an employee's duties. Non-intact skin would include acne, cuts, abrasions, dermatitis, or hangnails. Examples include needle sticks or splashing of infectious material onto the face (CDC, 2024d; Hollier, 2021; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; OSHA, n.d.).

While performing patient care, HCPs are often exposed to bodily fluids. Due to this, they must understand the pathophysiology of the virus, its impact on health care, and the need for protective precautions. While HIV is found in feces, urine, tears, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, cervical cells, lymph nodes, corneal tissue, and brain tissue, these are not the most common transmission methods. Because HIV cannot live long outside the human body, the risk of transmission is decreased for HCPs. Despite this, careful precautions to protect those caring for individuals with HIV/AIDS must still be taken (CDC, 2024d, 2024e; OSHA, n.d.).

Although the CDC notes that less than 1% risk exists after percutaneous exposure to HIV and almost none after splashes or intact mucous membrane exposure, any risk is too much for an individual HCP. Infection control includes two tiers of recommended precautions to decrease the risk of exposure to workers and the spread of infections within the health care system. The first tier consists of standard precautions, which should be maintained for all patients regardless of infection status. The second is transmission-based precautions used with certain known or suspected infections. Primary prevention with standard precautions for occupationally acquired HIV infection is the most important prevention strategy (CDC, 2024d, 2024h, 2024i). Second-tier transmission-based precautions include contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. Regardless of the specific type of transmission-based precautions required, the following principles should be routinely adhered to (CDC, 2024i):

- Thoroughly perform hand hygiene before entering and leaving the room of a patient in isolation.

- Properly dispose of contaminated supplies and equipment according to agency policy.

- Apply knowledge of the mode of infection transmission when using PPE.

- Protect all persons from exposure during the transport of an infected patient outside of the isolation room.

- Single private rooms are preferred when available, but cohorting may be implemented during outbreaks of infections (the placement of patients infected with the same organism in the same room, based on organizational needs).

Diagnosis

It is estimated that 13% of individuals with HIV in the United States are unaware that they are infected, and these individuals cause 40% of new HIV infections. For this reason, routine screening is recommended. Primary HCPs are the front line of screening and testing patients for HIV, and, therefore, preventing transmission. Unfortunately, over 75% of patients from one or more high-risk groups seen by their primary HCP within the previous 12 months were not offered HIV testing. HIV diagnosis is frequently delayed in nonwhite persons, individuals who inject drugs, residents of rural areas, and those who are advancing in age. Due to this delay, many of those individuals develop an AIDS-defining illness within one year of diagnosis (CDC, 2024a, 2025e; HHS, 2024a).

Laboratory testing is the only means to verify infection with HIV. The CDC and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend that everyone between the ages of 15 and 65 and those who are pregnant be tested for HIV at least once during routine care. HIV testing should also be included whenever a patient is seeking evaluation for a possible STI. Individuals at a higher risk of contracting HIV (e.g., sexually active gay, bisexual, or other MSM individuals) should be tested annually, with some providers recommending testing as frequently as every 3 to 6 months. When patients understand their HIV status, it allows them to make fully informed decisions about treatment options and take action to protect their sexual partners. While testing is recommended by the USPSTF and offers significant benefits, it should remain voluntary. Patients must always provide informed consent and should never undergo testing without their knowledge (CDC, 2021b, 2024b; HHS, 2024a; USPSTF, 2019).

Testing

Diagnosing an HIV infection can involve several steps. Previously, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot or indirect immunofluorescence assay were performed to confirm a diagnosis. Research and revision of testing strategies have led to more specific and accurate immunoassay tests that can accurately confirm the diagnosis sooner. Currently, three tests are used to diagnose HIV: nucleic acid (NATs), antigen/antibody combination, and antibody tests. These tests use blood, saliva, or urine for results (CDC, 2025e; Sax, 2024a).

The antibody test is the quickest of the three tests and is designed for home and rapid point-of-care (POC) testing. The HIV antibody test identifies HIV immunoglobulin M (IgM) or immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies in the blood or saliva. Rapid antibody POC screening with a fingerstick or saliva can provide results within 20 minutes and is used in most clinical settings. The oral (saliva) antibody home test kit also provides results within 20 minutes. These kits are available both online and in retail stores. The home serum collection kit is done by fingerstick, and the person testing sends the sample of blood by mail to a licensed laboratory for antibody testing. Results are available as quickly as the next day. The manufacturers of these tests provide counseling and referrals for further testing and treatment. If a rapid antibody test is positive, follow-up testing with an antigen/antibody immunoassay is needed to confirm the results (CDC, 2021b, 2024b; Sax, 2024a).

The CDC recommends that HIV testing begin with a laboratory-based, FDA-approved antigen/antibody immunoassay that detects HIV-1 and HIV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies and p24 antigen. This antigen can be detected very early after exposure to the virus, even before antibody formation. Since 2014, the CDC has recommended that when diagnosing HIV, a supplemental HIV-1/HIV-2 differentiation test be performed to confirm the infection type based on the presence of specific antibodies. If the specimen is nonreactive, no further testing is required unless there is a possibility that the patient was recently exposed or is taking post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) or PrEP, and virus levels are still undetectable. This is known as the eclipse period. The window period is the time following infection that extends until a substance is produced in enough quantity to be identified by a particular laboratory test. If this is the case, an HIV-1 nucleic acid test (NAT) should be performed or a new specimen obtained and antigen/antibody combination testing repeated after a few weeks (CDC, 2021b, 2024b; Peruski et al., 2020; Sax, 2024a; Wood, 2024).

A NAT identifies HIV RNA in the blood. It is an expensive test and is not recommended for screening except for high-risk or potential exposure with the presence of HIV symptoms. The NAT is very accurate during the early stages of infection, but an antigen/antibody combination test should be done to confirm the results if the NAT is negative. The accuracy of the NAT results may be compromised in individuals taking PrEP or PEP (CDC, 2021b, 2024b; Sax, 2024a).

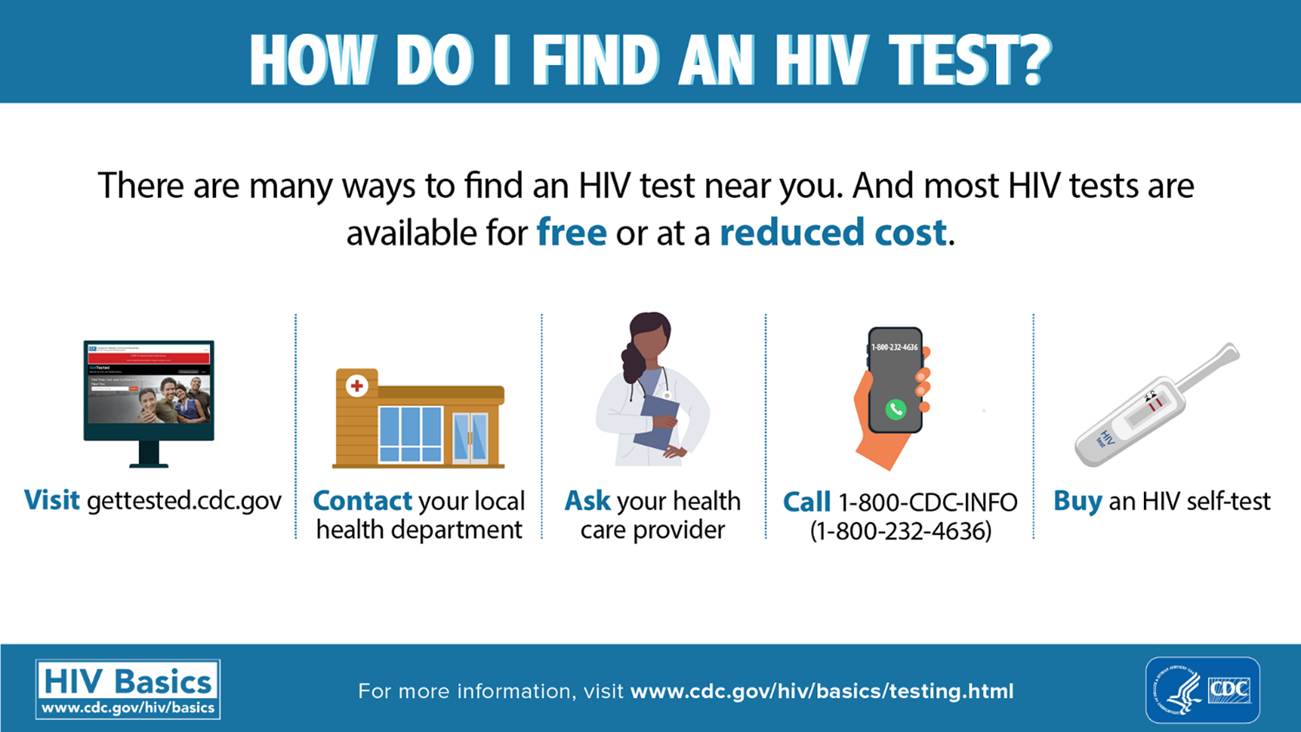

Considering the broad USPSTF recommendations on testing, the CDC has ensured that testing is available to all at free or reduced cost in the United States (refer to Figure 3; CDC, 2024g).

Figure 3

How to Find an HIV Test

(CDC, 2024g)

Testing for Drug Resistance

HIV is skilled at mutating and changing its structure. This enhances drug resistance, which occurs when previously effective medications become ineffective. Following the initial diagnosis of HIV, the patient should undergo an HIV-1 RNA quantification to determine the viral load, an antiretroviral resistance assay to assess for medication sensitivity, and a CD4+ count to assist with staging. These results will guide the patient's treatment plan. Genotypic testing is the preferred resistance testing to guide therapy in ART-naïve patients. However, ART initiation should not be delayed while awaiting the results of resistance testing; therapy can be modified after results are obtained. For patients already being treated with ART, HIV drug resistance testing should be performed to assist in modifications of drug selection (HHS, 2024a, 2025b; Sax, 2024a). This applies when changing ART regimens in patients who have:

- virologic failure and HIV RNA levels > 1,000 copies/mL

- HIV RNA levels 500–1,000 copies/mL (drug resistance testing may be unsuccessful, but should be considered in this group)

- suboptimal viral load reduction (HHS, 2024a)

Counseling

All patients who receive HIV testing should be counseled after test results are known. For those with negative tests, counseling should be aimed at education on behaviors that prevent acquiring HIV, including PrEP and PEP as appropriate. With a suspected or confirmed case of HIV, counseling aims to educate patients on behaviors that prevent transmitting HIV, treatment, and support services. Historically, when an HIV test was performed, it took several days for the results to come back. Due to this delay, comprehensive pre-test counseling was completed in case the individual did not return for their test results. With the widespread use of rapid diagnostic tests, most individuals receive test results and possibly a diagnosis on the same day. Pre-test counseling is no longer recommended due to the quick turnaround. Once test results are obtained and verified, post-test counseling should be provided. Post-test counseling should be individualized and patient centered. This counseling can be delivered by any HCP or lay person trained to provide HIV counseling and should include the following (Sax, 2024a; WHO, 2024a):

- explanation of the test results and diagnosis

- assistance for coping with the emotional response to the diagnosis

- discussion of any immediate concerns

- information on ART and the importance of medication compliance

- enrollment of the patient into HIV clinical care

- arrangement of follow-up appointments

- information on preventing transmission and the risks and benefits of disclosure, especially among partners

- assessment of potential intimate partner violence, risk of suicide, depression, and changes in mental health following diagnosis

- additional referrals for other services as appropriate, such as access to sterile needles, opioid substitution therapy, and contraception (WHO, 2024a; Wood, 2024)

Absorbing, understanding, and retaining all this information in one counseling session can be overwhelming for an individual just diagnosed with HIV. Follow-up counseling is recommended to reiterate the education provided in the initial post-test counseling session (WHO, 2024a).

Confidentiality

HCPs should inform patients who test positive for HIV about any legal reporting obligations. They should reassure the patient that testing and results are confidential and cannot be shared with anyone outside of those legal obligations. In states where partner notification is not mandatory, HCPs should encourage patients with positive HIV tests to notify all prior partners and offer to assist as needed (CDC, 2021b, 2024b; WHO, 2024a).

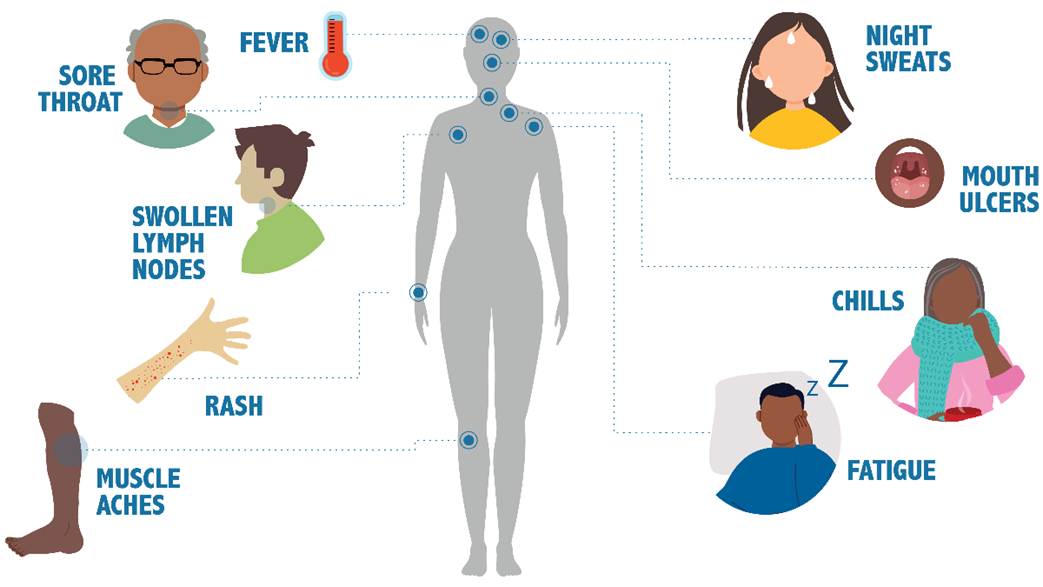

Clinical Manifestations

Primary HIV infection occurs within the first few weeks after contracting HIV. A high viral load during this phase indicates that infected individuals are more likely to pass the disease to others, yet they may be unaware of their HIV status. Early HIV symptoms are flu-like and include fever, lymphadenopathy (swollen glands in the neck, armpits, or groin), rash, fatigue, night sweats, chills, muscle aches, mouth ulcers, and sore throat (refer to Figure 4). The individual may think they have the flu or other viral illness unless they have a reason to suspect HIV. An inaccurate diagnosis may occur as these symptoms are vague and typically subside in days to weeks (CDC, 2025a; HHS, 2023).

Figure 4

Early Symptoms of HIV

(CDC, 2025a)

Seroconversion occurs between the initial exposure and the time antibodies can be detected on an HIV test. Seroconversion can vary but typically occurs between nine days and six months after exposure. Asymptomatic HIV is a term used to describe patients with positive results on their HIV test(s) but no clinical symptoms. This period may last up to 10 years with no outward appearance of illness. Without verification through testing, the individual may be unaware they are infected. There are no specific HIV symptoms; however, HIV affects the normal functioning of the immune system, the kind and number of blood cells, the body's metabolism, the structure and function of the brain, and the amount of fat and muscle distribution in the body (CDC, 2025a; HHS, 2021; Sax, 2024a). Clinical manifestations can include:

- persistent low-grade fever

- unintentional weight loss

- persistent headaches

- difficulty recovering from illnesses, or more severe than typically experienced

- diarrhea lasting more than a week

- loss of muscle, tissue, and body weight

- thrush (yeast infection in the mouth)

- vision or hearing loss

- nausea or vomiting

- osteoporosis

- confusion, memory loss, or dementia

- extreme and unexplained fatigue

- urinary or fecal incontinence

- sores of the mouth, anus, or genitals

- dry cough (CDC, 2025a; HHS, 2023; Sax, 2024a; Wood, 2023)

HIV in persons assigned female at birth can lead to several gynecological problems, including pelvic inflammatory disease, abscesses of the fallopian tubes and ovaries, and recurrent yeast infections. Those with human papillomavirus (HPV) are at an increased risk of cervical dysplasia and cancer when coinfected with HIV. Invasive cervical cancer is considered an AIDS-defining condition. Routine screening for cervical cancer is recommended for nearly all persons assigned female at birth, but it is crucial for those diagnosed with HIV. Persons assigned female at birth in the United States receive fewer health care services than those assigned male at birth and may not be diagnosed with HIV until later in the disease process, making the disease harder to control (Aberg & Cespedes, 2024; CDC, 2021b, 2024b).

Staging

HIV infection was originally considered a single, continuous disease process that progressed to AIDS. Research quickly identified three stages, which were updated in 2014 to include a fourth stage, stage 0, which consists of the period of initial infection with HIV. The stages progress from initial infection to the development of AIDS (stage 3). Therefore, a patient with HIV does not necessarily have AIDS, but any patient who has AIDS has previously acquired the HIV infection. Patients in stage 3 are severely immunocompromised and require complex care. Stages 1, 2, and 3 are determined using the patient's CD4+ count or the CD4+ percentage when the count is unavailable. The patient is considered "stage unknown" if neither of these findings is available, although some experts classify this as a separate fifth stage (CDC, 2014, 2022, 2025b; Wood, 2023).

Stage 0

Stage 0 is used to represent early HIV infection. If there was a negative or indeterminate HIV test within six months of initial diagnosis, the stage is 0 until six months after diagnosis. The classification of stage 0 can also be based on a testing algorithm using laboratory testing that shows the presence of HIV-specific markers such as p24 antigen or nucleic acid within six months of a negative antibody test. Even though titers are negative, the patient can transmit the disease during this time. It can take up to six months for antibodies to show up on tests, although they typically appear six weeks after exposure. Although the stage at diagnosis does not change once the six months from diagnosis have elapsed, the stage is classified depending on CD4+ T-lymphocyte test results or whether an opportunistic illness has been diagnosed (CDC, 2022, 2025b; Swinkels et al., 2024).

Stage 1

The first flu-like manifestations of the disease process typically occur within four weeks of infection (refer to Figure 4). This stage is marked by a rapid rise in the HIV viral load, decreased CD4+ cell counts, and increased CD8+ cell counts. Individuals in stage 1 will have all of the following characteristics:

- absence of an opportunistic AIDS-defining condition

- CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of 500 cells/mm3 or more

- CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage (of total lymphocytes) of 26% or more (CDC, 2021b, 2022, 2024b; Hollier, 2021; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Swinkels et al., 2024; Wood, 2023)

The resolution of the initial viral manifestations of HIV infection coincides with the decline in viral HIV copies. However, lymphadenopathy persists throughout the disease process (CDC, 2025b; Swinkels et al., 2024).

Stage 2

Stage 2 is known as the latency stage, as patients are noted to be asymptomatic due to the decline in viral HIV copies. This decline results from the body's immune system attacking and minimizing the virus, not eliminating it. This stage can be prolonged, allowing patients to remain asymptomatic for up to 10 years without taking medication and for decades if on ART. During this stage, anti-HIV antibodies are produced, so the patient's tests for these are positive. The viral set point is the amount of virus, or viral load, remaining in the body after the immune system's efforts to eliminate the virus. This set point relates directly to the patient's prognosis, as a high viral set point typically equates to poorer outcomes for the patient (CDC, 2021b, 2024b, 2025b; Wood, 2023).

Over time, the virus will use the host's genetic machinery to replicate itself. The viral load increases, and CD4+ cells are destroyed. This process results in a dramatic loss of immunity that can have life-threatening consequences for the patient and is a significant concern for health care delivery. Stage 2 has all of the following characteristics:

- Absence of an opportunistic AIDS-defining condition

- CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of 200 to 499 cells/mm3

- CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage (of total lymphocytes) of 14% to 25% (CDC, 2022; Hollier, 2021; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Wood, 2023)

As evidenced by the decrease in the CD4+ count and CD4+ percentage compared to stage 1, the patient is experiencing a significant loss of immunity secondary to the virus becoming more active. This loss of immunity places the patient in a more vulnerable position as they progress into the third stage of the disease process (CDC, 2021b, 2024b, 2025b; Wood, 2023).

Stage 3

Stage 3 is the final stage of HIV infection, and if the patient does not receive treatment, death is likely to occur within three years. Stage 3 of the disease process involves the development of AIDS. AIDS is a combination of symptoms and infections stemming from an impaired immune system. HIV-infected individuals become vulnerable to diseases or infections known as "opportunistic," as these illnesses would not impact individuals with a fully functioning immune system. Modern-day medical treatments can significantly delay the progression of HIV and subsequent diagnosis of AIDS (CDC, 2025b; HHS, 2021). This stage is typically defined through the presentation of all of the following characteristics:

- presence of an opportunistic AIDS-defining condition

- CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts less than 200 cells/mm3

- CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes less than 14% (CDC, 2025a; Hollier, 2021; Rogers & Brashers, 2023)

However, patients are considered in stage 3 of the disease if an AIDS-defining condition is present, even if the CD4+ count or percentage is higher than expected for this stage. Stage 3, unlike stages 1 and 2, is characterized by a variety of defining conditions and presents severe health challenges for the patient, who is often extremely ill. To plan appropriate care, the nurse should know the pathophysiology and defining conditions related to this stage. Since the patient has the potential to develop more than one AIDS-defining illness, this can present a challenge for the health care team when planning and delivering care (CDC, 2025a; Sax, 2024d; Wood, 2023). The patient should be educated on precautions that are advised for patients with HIV stage 3, including:

- Do not eat raw fruits or vegetables without thoroughly washing them.

- Do not consume unpasteurized dairy or juice products. Choose hard cheeses over soft cheeses as they tend to harbor fewer harmful pathogens.

- Avoid changing a cat’s litter box due to the risk of contracting cytomegalovirus (CMV); if unavoidable, a facemask and rubber gloves are recommended.

- Avoid contact with individuals who are ill; a mask is advised for any imperative public outings (CDC, 2025a; FDA, 2022; Medline Plus, 2024; Sax, 2024d).

The following is a list of AIDS-defining conditions (they differ slightly according to the CDC and WHO; refer to Table 1):

Table 1

AIDS-Defining Conditions

CDC | WHO |

Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrent | Severe bacterial infections (e.g., pneumonia, empyema, pyomyositis, bone or joint infection, meningitis, bacteremia) |

Candidiasis (of bronchi, trachea, lungs, or esophagus) | Persistent oral or esophageal candidiasis |

Cervical cancer, invasive | |

Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary | |

Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary | |

Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (>1 month's duration) | |

CMV disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes), onset at age >1 month | |

CMV retinitis (with loss of vision) | |

Encephalopathy, HIV-related | HIV encephalopathy |

Herpes simplex—chronic ulcers (>1 month's duration) or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis (onset at age >1 month) | Chronic herpes simplex infection (orolabial, genital, or anorectal of more than one month's duration) |

histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary | |

Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1 month's duration) | |

KS | KS |

Lymphoma, Burkitt (or equivalent term), immunoblastic (or equivalent term), or primary of the brain | |

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary | |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) of any site, pulmonary, disseminated, or extrapulmonary | Pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB (current) |

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) | PCP |

Pneumonia, recurrent | Recurrent severe bacterial pneumonia |

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | |

Salmonella septicemia, recurrent | |

Toxoplasmosis of the brain, onset at age >1 month | CNS toxoplasmosis |

Wasting syndrome attributed to HIV | HIV wasting syndrome Unexplained severe weight loss (>10% of presumed or measured body weight) |

Oral hairy leukoplakia | |

Acute necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis, gingivitis, or periodontitis | |

Unexplained persistent fever (above 37.6° C intermittent or constant for longer than one month) | |

Unexplained chronic diarrhea for longer than 1 month |

(Wood, 2023).

The progression of HIV to AIDS has been dramatically slowed in the United States by ART, yet in less developed countries the progression can be remarkably rapid due to limited access to ART. While ART has been shown to slow or temporarily halt disease progression, specific cofactors can exacerbate the advancement of HIV to AIDS (CDC, 2021b, 2024b, 2025g; Wood, 2023). These include:

- smoking

- advanced age

- substance or alcohol use

- poor nutrition

- coinfection with TB, fungal infection, helminthic infection, or any STI (CDC, 2025g; Wood, 2023)

The average time lapse from HIV infection to AIDS in untreated patients is 8 to 10 years. After a diagnosis of AIDS, the prognosis varies based on medication compliance, baseline CD4 count, viral load, age, substance use, concomitant conditions, host immune response, and genetic factors (CDC, 2021b; Wood, 2023).

Treatment

Pharmacologic

According to the WHO, AIDS-related deaths fell by 69% between 2004 and 2023 due to international efforts with ART and education. In 2023, 77% of the 39.9 million people living with HIV were receiving ART therapy globally. The CDC recommends that all HIV-positive individuals begin ART upon diagnosis, regardless of their health status or duration of HIV infection. HIV is not curable; however, ART can help slow virus replication and reduce viral load (CDC, 2021b; WHO, n.d., 2024b, 2024c). The nurse should educate the patient on the benefits and risks of ART therapy and the importance of strict and consistent adherence to treatment. ART reduces HIV-related morbidity and mortality throughout the disease process, decreases and suppresses the viral load, maintains CD4+ cell counts, delays the progression to AIDS, improves survival rates, and reduces the risk of transmission to others (CDC, 2024b; Sax, 2024a).

The treatment goals of ART include providing a long, high-quality life, promoting optimal immune function, and minimizing the HIV viral load to lower the risk of transmission to others. Specific medications work at various stages of HIV replication; therefore, for maximum efficacy, most patients must follow a multi-drug HIV regimen. Taking a combination of drugs also helps to prevent medication resistance, reduce adverse effects, and decrease the dosage required for each medication. ART is constantly changing as new research emerges, but as of 2025, it consisted of 25 medications in ten classes and 22 combination medications. The initial selection of ART for treatment-naïve patients is influenced by patient preferences, baseline lab results (e.g., kidney and LFTs), profiles of adverse effects and drug interactions, coinfection with viral hepatitis, other comorbid conditions, and allergies to drugs. Current US panel International Antiviral Society recommendations for ART in naïve patients include an oral second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI; preferred is either bictegravir [Biktarvy] or dolutegravir [Tivicay]) plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs; Gandhi et al., 2025; Goldschmidt & Chu, 2021; HHS, 2024a; New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute, 2025; Sax, 2024a). Table 2 outlines the different ART medication categories, examples, adverse reactions, and considerations.

Table 2

Antiretroviral Therapy Medications (ARTs)

Drug | Adverse Reactions (AR) | Considerations

| |||||||

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) inhibit reverse transcriptase and incorporate it into the viral DNA, resulting in DNA chain termination. | |||||||||

abacavir (ABC; Ziagen) | fever, chills, headache, insomnia, anxiety, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, rash |

| |||||||

emtricitabine (FTC; Emtriva) | skin rash, hypercholesterolemia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, abnormal dreams, asthenia, dizziness, headache, insomnia, cough, rhinitis, increased ALT, AST, amylase, bilirubin, creatine kinase (CK), lipase, glucose, and triglycerides, decreased neutrophil count |

| |||||||

lamivudine (3TC; Epivir) | headache, fatigue, malaise, paresthesia, peripheral neuropathy, neuropathy, insomnia, sleep disorder, skin rash, nausea, diarrhea, pancreatitis, sore throat, vomiting, hepatomegaly, infection, musculoskeletal pain, cough, nasal signs and symptoms, fever, dizziness, chills, depression, neutropenia, increased serum ALT, amylase, and lipase |

| |||||||

tenofovir alafenamide (TAF; Vemlidy) | headache, decreased bone density, skin rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dyspepsia, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, glycosuria, fatigue, arthralgia, back pain, cough, increased serum amylase, cholesterol, CK, and ALT |

| |||||||

tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF; Viread) | headache, pain, fever, peripheral neuropathy, insomnia, dizziness, sinusitis, chest pain, nausea, abdominal pain, anorexia, flatulence, rash, pruritus, diaphoresis, hematuria, neutropenia, hyperglycemia |

| |||||||

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) bind non-competitively to HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and prevent viral RNA conversion to DNA. | |||||||||

doravirine (DOR; Pifeltro) | skin rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, increased serum CK, lipase, bilirubin, ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, and serum creatinine |

| |||||||

efavirenz (EFV; Sustiva) | skin rash, diarrhea, dizziness, central nervous system (CNS) toxicity, depression, insomnia, anxiety, pain, increased serum cholesterol and triglycerides |

| |||||||

etravirine (ETR; Intelence) | skin rash, diarrhea, hypercholesterolemia, increased serum glucose |

| |||||||

nevirapine (NVP; Viramune) | hepatic impairment, decreased serum phosphate, hypercholesterolemia, increased serum ALT |

| |||||||

rilpivirine (RPV; Edurant) | skin rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, hypercholesterolemia, increased serum ALT and AST |

| |||||||

Protease inhibitors (PIs) inhibit the protease enzyme needed for the virus to replicate. | |||||||||

atazanavir (ATV; Reyataz) | skin rash, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, scleral icterus, cough, fever, cardiac dysrhythmias, increased serum cholesterol, bilirubin, CK, and amylase |

| |||||||

darunavir (DRV; Prezista) | skin rash, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, fatigue, hyperlipidemia, increased serum glucose |

| |||||||

lopinavir/ritonavir boosting (LPV/r; Kaletra) | diarrhea, dysgeusia, vomiting, upper respiratory tract infection (URI), increased gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and serum ALT |

| |||||||

ritonavir (RTV; Norvir) | flushing, pruritis, skin rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dysgeusia, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, fatigue, asthenia, feeling hot, paresthesia, arthralgia, back pain, cough, oropharyngeal pain, hypercholesterolemia, increased serum triglycerides, CK, and GGT |

| |||||||

Fusion inhibitors act as an antiretroviral by inhibiting the fusion of proteins. | |||||||||

enfuvirtide (T-20; Fuzeon) | fatigue, insomnia, diarrhea, nausea, injection site reaction, weight loss, eosinophilia, increased creatine phosphokinase |

| |||||||

Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) block the enzyme integrase, which in turn keeps HIV from inserting its DNA into the host DNA. | |||||||||

cabotegravir (CAB; oral, Vocabria/IM Apretude) | induration, pain, nodule, reaction, or tenderness at the injection site, headache, rash, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, increased serum CK, ALT, and AST |

| |||||||

dolutegravir (DTG; Tivicay) | pruritis, hyperglycemia, abdominal pain or distress, diarrhea, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, depression, fatigue, headache, insomnia, suicidal ideation or tendencies, neutropenia, hepatitis, hyperbilirubinemia, renal insufficiency, increased serum lipase, CK, creatinine phosphokinase, ALT, and AST, |

| |||||||

raltegravir (RAL; Isentress, Isentress HD) | abdominal pain, decreased appetite, diarrhea, dyspepsia, flatulence, gastritis, nausea, vomiting, genital herpes simplex, hypersensitivity reaction, herpes zoster, abnormal dreams, asthenia, depression, dizziness, fatigue, headache, insomnia, nightmares, suicidal ideation or tendencies, increased serum ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, amylase, lipase, fasting glucose, creatinine, and bilirubin, decrease in absolute neutrophil count and hemoglobin |

| |||||||

CCR5 Antagonists block the CCR5 receptor on CD4+ T-cells to prevent the entry of HIV into the cell. | |||||||||

maraviroc (MVC; Selzentry) | skin rash, vomiting, infection, bronchitis, cough, URI, fever, cane, alopecia, folliculitis, nail disease, pruritis, sweat gland disease, tinea, lipodystrophy, abdominal distension, bloating, or pain, appetite change, decreased motility of gut, nausea, sexual dysfunction, anemia, malignancies, liver dysfunction, dizziness, depression, anxiety, anxiety, insomnia, epilepsy, paresthesia, peripheral neuropathy, arthropathy, myalgia, rhabdomyolysis |

| |||||||

Attachment inhibitors bind to the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 directly and prohibit attachment of the virus or entry of the virus into host T cells. | |||||||||

fostemsavir (Rukobia) | pruritis, skin rash, hyperglycemia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dysgeusia, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, decreased hemoglobin and neutrophils, dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, headache, peripheral neuropathy, sleep disturbance, myalgia, increased serum creatinine, CK, triglycerides, cholesterol, ALT, AST, and bilirubin, prolonged QT on ECG |

| |||||||

Post attachment inhibitors block CD4+ receptors on the surface of specific immune cells that HIV needs to enter the cells. | |||||||||

ibalizumab (IBA; Trogarzo) | rash, diarrhea, nausea, dizziness, decreased hemoglobin, neutrophils, and platelets, leukopenia, increased serum glucose, lipase, bilirubin, and creatinine |

| |||||||

Capsid inhibitors consist of small molecules that interrupt HIV capsid protein functioning which impact key interactions necessary for the virus to enter and assemble. | |||||||||

lenacapavir (LEN; Sunlenca) | injection-site reaction, nausea, glycosuria, proteinuria, increased serum creatinine, bilirubin, ALT, and AST, hyperglycemia |

| |||||||

PK enhancers (CYP3A Inhibitors) increase the effectiveness and systemic exposure of other HIV drugs. | |||||||||

cobicistat (Tybost) | skin rash, hyperglycemia, diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting, abnormal dreams, depression, fatigue, headache, insomnia, rhabdomyolysis, scleral icterus, renal dysfunction, hyperbilirubinemia, increased serum CK, amylase, lipase, GGT, ALT, and AST, glycosuria, hematuria, decreased neutrophils |

| |||||||

(Arcangelo, 2022; Fletcher, 2025; Gandhi et al., 2025; HHS, 2024a)

Medication adherence and viral suppression drive the successful outcomes of ART therapy. Effective ART use can reduce the viral load to undetectable within 12 to 24 weeks of treatment. The following are predictive factors of effective ART (virologic success; HHS, 2024a):

- low baseline viremia

- high potency of the ART regimen

- tolerability of the regimen

- convenience of the regimen

- excellent adherence to the regimen

Proper administration of the medication regimen leads to viral suppression, and undetectable levels of the virus are possible. As previously mentioned, the concept of U=U has been recognized as scientifically sound among most experts. The National Institute of Health's (NIH's) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) reviewed the extensive scientific evidence behind U=U, leading to widespread acceptance of the concept. The validation of HIV treatment as a prevention strategy adds additional rationale for compliance with ART among HIV-positive patients and further decreases the stigma surrounding an HIV diagnosis. For the virus to remain undetectable, strict compliance with ART is necessary (CDC, 2024b; 2024j; NIAID, 2025a; 2025b).

In the few months following ART initiation, up to 30% of patients develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) due to the sudden boost in the body's immune capabilities. IRIS results in an exaggeration of symptoms associated with opportunistic pathogens that are present in the patient's body (e.g., TB, hepatitis, and CMV). Treatment of the underlying infection and adjunctive corticosteroids may be required to reduce inflammation and resolve this condition (HHS, 2024a; Sax, 2024c).

Additionally, the patient might require drugs to treat secondary or opportunistic conditions, such as antineoplastic medications, antivirals, or antifungals, or to combat adverse effects, such as antiemetic or antidiarrheal medications. If the patient has depression, antidepressants such as imipramine (Tofranil) and fluoxetine (Prozac) might be prescribed. These also have secondary beneficial effects, such as reducing fatigue and lethargy. In patients who have substance use disorder, methylphenidate (Ritalin) can reduce cravings for or the use of methamphetamine (HHS, 2024a).

Treatment with ART can cost thousands of dollars per month. Cost savings are substantial, however, when treatment is initiated as early as possible. Government insurance programs offer coverage for HIV-related medical visits and medications. Private health insurance is required to pay for many of the medications used to treat HIV; however, the co-pays may be high, causing the patient financial hardship. For the patient without health insurance, assistance is available through government programs, including Medicaid, Medicare, the Ryan White AIDS Program, and other resources such as the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (CDC, 2024b; HHS, 2024a; Hyle & Dryden-Peterson, 2025).

Patient Monitoring

Nurses should assist with patient monitoring:

- Follow-up is recommended four weeks (or sooner) after initiation of ART with ongoing visits every three to six months.

- Obtain a list of all prescribed, over-the-counter, and herbal medications the patient is taking to check for interactions.

- Have labs ready for provider review (e.g., HIV RNA, total CD4, ALT, AST, bilirubin, mean corpuscular volume, high-density lipoproteins, total cholesterol, and triglycerides).

- Reinforce patient teaching about the potential adverse effects of the medications and explore ways to decrease the severity of adverse effects to promote adherence to the prescribed treatment regimen (CDC, 2024b; Garland, 2025; HHS, 2024a).

Medication-Specific Patient Education

As a patient advocate, the nurse should educate the patient on the following (Cachay, 2024; CDC, 2024b; Garland, 2025; HHS, 2024a):

- Medications should be taken on a regular schedule without missing doses. Missed medication doses can cause medication resistance. The goal is 95% on-time dosing to maintain viral suppression.

- Protocols for missed doses specific to the medications prescribed should be followed.

- Medication administration timing, restrictions, and potential interactions with food or other substances should be thoroughly explained.

Complementary Therapy

A majority (up to 80%) of patients who have HIV use complementary and alternative medicines and therapies (CAMs) to alleviate the adverse effects of HIV/AIDS and ART (Anthamatten, 2022; Bordes et al., 2020). Commonly used CAM and recommendations include the following:

- Supplements may be helpful, such as vitamin D to promote bone health (no interactions reported), vitamin C to boost immune function (use with caution in conjunction with indinavir [Crixivan] and ritonavir [Norvir]), and vitamin E for cardiovascular benefits (contraindicated for use with tipranavir [Aptivus]).

- Minerals such as calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, and zinc may have bone, blood, or musculoskeletal benefits; they are contraindicated with raltegravir HD (Isentress HD) and should either be given with a meal or separated by six hours before or two hours after administration with bictegravir (Biktarvy), dolutegravir (Tivacay), elvitegravir (Vitekta), and raltegravir (Isentress).

- Herbal products such as echinacea and ginseng may improve immunity; caution is advised when used with maraviroc (Selzentry), rilpivirine (Cabenuva), ritonavir (Norvir), lopinavir (Kaletra), and darunavir (Prezista).

- Orange peel may stimulate appetite, but a four-hour interval between its use and ART is recommended.

- Whey protein may increase muscle mass but should be avoided for use with efavirenz (Sustiva), nevirapine (Viramune), tipranavir (Aptivus), ritonavir (Norvir), indinavir (Crixivan), atazanavir (Reyataz), didanosine (Videx), stavudine (Zerit), and tenofovir (Vemlidy or Viread) due to hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic effects.

- Generally, there are no contraindications to physical therapy, occupational therapy, yoga, massage, and acupuncture, and these should be encouraged if desired.

- Relaxation techniques to alleviate stress and fatigue, such as meditation, visualization, guided imagery, and hypnosis, have no contraindications and should be encouraged if desired (Anthamatten, 2022; Bordes et al., 2020; HHS, 2021).

Prophylaxis

Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

PrEP is used to reduce the risk of contracting HIV in persons who are at high risk, including MSM, transgender persons assigned female at birth who report risky sexual behaviors (e.g., condomless anal sex), heterosexually active people whose sexual partners are at high risk for HIV, and persons who inject drugs. When taken as prescribed, PrEP can reduce the risk of acquiring HIV by 99%. The two most commonly used combinations for PrEP are oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF-FTC; Truvada) and tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (TAF-FTC; Descovy). Side effects are mild and include nausea and diarrhea; however, TDF can lead to bone and renal toxicity when used long-term. TAF has shown less renal and bone toxicity incidence, but side effects include weight gain and dyslipidemia (CDC, 2025d; Krakower & Mayer, 2024).

At the end of 2021, the FDA approved cabotegravir (CAB; Apretude) for use as PrEP. Injections should only be administered into the gluteal muscle as the pharmacokinetics of the medication are unknown if administered in a different muscle. Other ART should not be used during treatment with CAB. Self-administration is not currently approved; therefore, the patient must have injections administered by an HCP. Side effects include pain, redness, and induration at the injection site (CDC, 2025d; Krakower & Mayer, 2024).

Post-exposure Prophylaxis

PEP involves using ART to prevent an HIV infection in an HIV-negative individual with high-risk exposure to HIV (e.g., sex, sharing needles, or occupational exposure through needlestick). HIV can establish infection within 24 to 36 hours after exposure; therefore, patients seeking care within 72 hours of exposure should be evaluated quickly for PEP initiation. PEP is a 28-day course of a four-drug ART regimen. Adherence to the drug regimen is necessary for effectiveness. Treatment is generally well tolerated with minimal side effects of headache and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Early discontinuation is acceptable if the source is asymptomatic and tests negative with a laboratory-based antigen/antibody test or if the source has HIV and is on ART with a suppressed viral load <1000 copies/mL (especially <200 copies/mL; Aberg & Silvera, 2024; CDC, 2025c; Zachary, 2023).

Complications

The nurse should be knowledgeable about common complications that can affect a patient who is diagnosed with AIDS. These are described as AIDS-defining conditions (refer to Table 1 for a complete list). If a patient with advanced HIV (CD4 cell count <50 cells/μL) is not using effective ART, the average length of survival time is 12 to 18 months. The most common AIDS-defining conditions are:

- opportunistic infections

- wasting syndrome

- fluid and electrolyte imbalance

- HIV encephalopathy (Cachay, 2025; Swinkels et al., 2024; Wood, 2023)

Opportunistic Infections

Bacterial Diseases

- TB may be pulmonary or extrapulmonary (may be lymphatic), and negative skin testing does not necessarily rule out TB. A false-negative can occur if the patient's immune system is not strong enough to elicit a response to the injected purified protein derivative solution. TB coinfection can cause HIV progression to accelerate.

- STI coinfection is common in persons with HIV, however, the presence of untreated Treponema pallidum (syphilis) has been found to accelerate HIV progression.

- Bacterial pneumonia related to MAC is contracted in up to 40% of patients with advanced HIV and a CD4 cell count of <50 cells/μL. The patient may report pain, chills, shivering, wheezing, and coughing.

- Septicemia/sepsis can be caused by various infectious organisms, and due to a depleted immune system, harmful pathogens can proliferate and cause sepsis (Cachay, 2025; Sax, 2024c; Swinkels et al., 2024).

HIV-associated Malignancies

- KS is characterized by purple-blue lesions on the skin that usually occur on the extremities; there may be an invasion into the GI system, lymphatic system, lungs, and brain. Diagnosis is confirmed through biopsy, and antineoplastic medications are used for treatment.

- Cervical cancer is more aggressive in patients with HIV due to immunosuppression and is related to the presence of HPV.

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is common, which may cause psychomotor slowing and changes in mental status, resulting in seizures and apathy. Standard lymphoma treatment is usually ineffective for patients with AIDS.

- More aggressive forms of squamous cell carcinoma are associated with HIV infection (Cachay, 2025; Deeken & Pantanowitz, 2023; Swinkels et al., 2025).

Viral Diseases

- CMV is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality; it usually affects the retina and commonly causes blindness in patients who have AIDS. If the eyes are affected, the patient will report visual impairment along with weight loss, fatigue, and fever.

- Herpes simplex virus can affect the oral, perirectal, or genital areas; the course of illness is more severe than for healthy patients.

- Varicella lesions may be painful or necrotic (Cachay, 2025; Johnston & Wald, 2024; Sax, 2024d; Swinkels et al., 2024; Wood, 2023).

Fungal Diseases

- The initial manifestations of PCP are mild (dry cough, fever, chills) but can progress to respiratory failure within several days. It is common in patients with advanced HIV and a CD4 count <100 cells/μL, with a risk of 40% to 50%.

- Candidiasis (Candida albicans) occurs due to overgrowth of normal intestinal flora; it is commonly found in the oral cavity and esophagus, produces thick white exudate in the mouth, and can progress to ulcerations. Affected individuals report altered taste and may experience retrosternal burning (Cachay, 2025; Sax, 2024d; Swinkels et al., 2024; Wood, 2023).

Protozoal Diseases

- Toxoplasmosis (infection with Toxoplasmosis gondii) can result in toxic encephalitis and is accompanied by headache, altered mental status, and fever. The risk of contracting toxoplasmosis is 30% in patients with CD4 cell counts <100 cells/μL.

- Microsporidiosis is caused by a parasite; clinical findings depend on the organism, but diarrhea is the most common symptom.

- Cryptosporidiosis and Isosporiasis are parasites found in the small bowel mucosa; they can cause chronic, watery diarrhea in patients who have AIDS. For patients who are not immunocompromised, the infection usually lasts only one to two weeks.

- Leishmaniasis is transmitted by sandflies and has been correlated with inadequate environmental resources and a weakened immune system; usually found in underdeveloped areas. Clinical manifestations are associated with cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral lesions (Bern, 2024; Cachay, 2025; Hyle & Dryden-Peterson, 2025; Leder & Weller, 2024a, 2024b; Sax, 2024c, 2024d; Swinkels et al., 2024).

Interventions to reduce the incidence and severity of opportunistic infections include:

- Early and consistent treatment with ART to keep CD4 cell count >200 cells/μL

- Treatment with antineoplastic, antibiotic, analgesic, antifungal, or antidiarrheal medications as indicated

- Monitor for skin breakdown

- Monitor fluid intake and electrolyte status

- Help the patient maintain adequate nutrition, consult a dietitian if needed, and provide supplementation and appetite stimulants as indicated

- Advise the patient to avoid being in close contact with persons who are ill to protect the patient from acquiring other infectious conditions during treatment

- Educate the patient on signs that should be reported immediately to the HCP since recovery is often much longer and the risk of complications is higher (Cachay, 2025; Sax, 2024b, 2024d; Swinkels et al., 2024)

Wasting Syndrome

In 1987, the CDC recognized "wasting" as an AIDS-defining condition. Current guidelines define the condition as unintended weight loss of more than 10% in a year, more than 5% in six months, or a body mass index (BMI) of less than 20 kg/m2. Disease progression and mortality are related to weight loss in patients with AIDS and are characterized by depletion of fat and muscle tissue. Wasting may be due to multiple factors such as malignancy, malabsorption, decreased appetite and intake, and diarrhea. The nurse should address these underlying conditions to promote adequate intake and monitor the patient for weight loss. Sufficient intake is essential, and measures must be implemented to stimulate appetite (Bedimo et al., 2024; Cachay, 2025; CDC, 2022; International Association of Providers of AIDS Care [IAPAC], 2024; Swinkels et al., 2024). Interventions for wasting syndrome are likely to include:

- Monitor weight, calorie counts, intake, and output.

- Medications to control diarrhea, increase appetite, and combat GI tract infections.

- Maintain nutrition orally or through total parenteral nutrition (TPN) if necessary (Bedimo et al., 2024; Cachay, 2025; Drugs.com, n.d.; IAPAC, 2024; Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine [PCRM], 2023; Swinkels et al., 2024).

The nurse should educate all patients with HIV infection regarding wasting syndrome. Education should include:

- Initiate or maintain ART and change regimens for patients with virologic failure (the mainstay of treatment)

- Report weight loss immediately

- Eat at least six small meals daily

- Incorporate between-meal supplements and snacks into the diet

- Consume more calories and protein to prevent loss of muscle mass by adding the following foods: instant breakfast drinks, eggs, cheese, milkshakes, dried beans, peas, peanut butter, and cream-based soups and sauces

- Increase intake of fruits and vegetables to ensure adequate micronutrients in the diet

- Consider probiotic supplements, which studies have shown to improve gut health and improve CD4+ counts

- Perform mouth care several times daily to reduce pain and increase appetite

- Engage in strength-building exercises such as resistance exercises and modified weight training as tolerated (Bedimo et al., 2024; Cachay, 2025; IAPAC, 2024; Pahuja et al., 2023; PCRM, 2023; Swinkels et al., 2024)

Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance

Patients who have AIDS can develop fluid and electrolyte disturbances, most commonly hyponatremia and hyperkalemia. This may be secondary to the disease or related to adverse medication effects. The patient may also experience an imbalance of calcium, magnesium, or phosphorus (Cachay, 2025; Sterns, 2025; Swinkels et al., 2024). Interventions for fluid/electrolyte imbalance typically include:

- Monitor fluid status, particularly for indicators of dehydration

- Monitor kidney function and electrolyte levels every three to six months and report abnormal laboratory data promptly

- Observe the patient for physiological manifestations of electrolyte imbalance (changes in neuromuscular ability, vital signs, or deep tendon reflexes)

- Encourage the patient to drink water when thirsty and use electrolyte solution if exercising more than 30 minutes

- Make dietary adjustments to reduce diarrhea

- Ensure the patient is aware of potential electrolyte disturbances associated with each HIV stage and treatment option, and what to monitor for and when to report abnormalities (Cachay, 2025; Chukwu et al., 2023; Sterns, 2025; Swinkels et al., 2024)

HIV Encephalopathy

As AIDS develops, the patient may experience HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). When HIV cells infect the brain, they secrete neurotoxins, and the patient may begin to experience impairment with motor dysfunction, speech problems, and behavioral changes. Cognitive impairment may be marked by mental slowness/psychomotor slowing, memory problems, lack of concentration, depression/apathy, incontinence, and diminished spontaneity. These cognitive and behavioral symptoms may accompany a similar reduction in motor abilities, such as loss of fine motor control with associated clumsiness or lack of balance. The condition can progress to the absence of verbal response (mutism), spastic paraparesis, hallucinations, psychosis, seizure, and death. However, the specific symptoms of HAND may vary from person to person (Cachay, 2025; Clifford, 2025a; Swinkels et al., 2024).

Deterioration may be a prolonged and gradual process with varying levels of impairment as the disease progresses. It is essential to encourage the patient to maintain self-care and participate in ADLs for as long as possible. The nurse should attempt to engage them in skills and exercises to maintain and promote their cognitive and physical functioning. The level of care required will increase as the level of neurocognitive disorder worsens (Cachay, 2025; Clifford, 2025a, 2025b; Swinkels et al., 2024). Interventions may include the following:

- Initiate or maintain ART and change regimens for patients with virologic failure (the mainstay of treatment)

- Psychiatric evaluation and medications if indicated

- Maintenance of patient safety, including fall and seizure precautions

- Promotion of self-care by encouraging physical and cognitive exercises and promoting psychomotor skills

- Monitoring for worsening manifestations and possible need for assistance with care, especially if the ability for self-care is a concern

- Discussion of the effects of HIV on the brain, leading to impairment in thinking, emotions, and movement

- Validation of the patient's feelings of frustration that can result from cognitive and memory issues, muscle weakness, and clumsiness (Cachay, 2025; Clifford, 2025b; Pahuja et al., 2023; Swinkels et al., 2024)

Legal Issues

Laws that protect patients who have HIV and AIDS include the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and the Federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which protects patients who have HIV/AIDS from discrimination. It is unlawful to discriminate against anyone who has suspected or known HIV/AIDS. Anyone who has HIV/AIDS who feels discriminated against based on their disease should file a complaint with the Office for Civil Rights of HHS or the appropriate agency within their state. Other legal considerations when caring for patients with HIV include:

- Informed consent requires that a patient must be given thorough explanations and have the right to refuse testing or treatment.

- Confidentiality is required except in cases of mandatory reporting or emergency care.

- Federal mandates require timely reporting of HIV positive tests to the local health department (within 2 weeks; CDC, 2024f; HHS, 2024c, 2025a; Swinkels et al., 2024; US Department of Justice, 2020).

Patient Resources

National support services are available for individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Patients need to understand their rights and resources within the medical system. Those rights include safety, competent medical care, and confidentiality. The following resources for patients with HIV are listed on the CDC (2024f) website:

- Ryan White HIV/AIDS program is a resource that assists people who have HIV/AIDS after exhausting all other resources. They can get medical care and other services, regardless of their ability to pay. The website lists available resources: https://ryanwhite.hrsa.gov/hiv-care/services.

- Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS (HOPWA) is a federal program dedicated to the housing needs of people living with HIV/AIDS. This program is funded by the Housing and Urban Development Department. HOPWA makes grants available to local communities, states, and nonprofit organizations to serve the housing needs of those impacted by HIV/AIDS. Their website can be found at https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/hopwa/.

- The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the national health care law and has provisions to expand medical coverage for those who have HIV/AIDS. Each state will have varying coverage, and social workers or HCPs in a local area can guide the patient through available options. This website can help explain the ACA services for each state: https://www.greaterthan.org/campaigns/health-coverage-hiv-you/.

Special Populations

Children

In 2023, it was estimated that there were 1.4 million children aged less than 15 years infected who have HIV worldwide, with 120,000 of those cases diagnosed that year. Around 90% of these children reside in Africa south of the Sahara. Over 90% of pediatric cases of HIV infection are due to vertical maternal transmission (e.g., during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding), which is a significant impetus for maternal screening campaigns. Children who have HIV will have a different progression of the disease, and it often begins with nonspecific lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Children who have HIV may present with developmental delays, pneumonia, failure to thrive, or recurrent bacterial infections. Those infected earlier through pregnancy or delivery have a higher mortality rate at one year than those infected later through breastfeeding. Considering that up to half of children born infected with HIV will die by the age of two if ART is not initiated, the current recommendation is to start medications as soon as an HIV-positive status is determined. Research has shown that the overall prognosis of children infected with HIV is very good (similar to the general pediatric population) with early diagnosis and treatment. Uninfected children born to HIV-positive patients should receive six weeks of ART to reduce the possibility of HIV transmission (CDC, 2021b, 2024b; Gillespie & Mirani, 2024; HHS, 2024b).

Pregnant Patients

Patients who are pregnant and infected with HIV risk vertical maternal transmission to the fetus. Vertical transmission can occur if the pregnant person is infected with HIV and not on ART or lacks viral suppression. It is recommended that all patients who are pregnant be screened for HIV and counseled on their risk for HIV, and in some states, this screening is mandatory. The CDC recommends that all patients who are pregnant should be tested for HIV during the first prenatal appointment, and those at high risk should be tested again in the third trimester. Despite these recommendations, studies have revealed that less than 80% of pregnant patients report being tested for HIV. The nurse should discuss opt-out HIV testing with all patients who are pregnant. Early screening and initiation of ART can significantly decrease the risk of transmission to their babies (CDC, 2021b, 2024b; HHS, 2024d; Wood, 2024). A landmark study in 1994 demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of transmitting HIV with the use of zidovudine (Retrovir) in patients who were pregnant with HIV infection (Huges & Cu-Uvin, 2025). Treatment with ART should begin immediately to reduce the risk of transmission to the fetus. Many factors influence treatment decisions, such as drug resistance, previous ART treatment, convenience of the regimen, and the safety and efficacy of the medications (CDC, 2021b, 2024b; HHS, 2024d; Hughes & Cu-Uvin, 2025).

The Aging Population

As treatment options improve, patients diagnosed with HIV are living longer. In 2022, 50% of individuals diagnosed with HIV were over the age of 50. HIV treatment in patients over 50 years of age comes with additional challenges. Individuals advancing in age are more likely to experience serious non-HIV complications. As the individual ages, they also acquire more comorbid conditions, increasing the need for medical intervention. Due to physiological changes, adults over 50 years of age are also more susceptible to side effects and adverse drug effects. In addition, polypharmacy is more prevalent in individuals of advancing age, increasing the risk of drug-drug interactions (Greene, 2024; HHS, 2024a).

Many adults over 50 years old engage in sexual behaviors that put them at risk for HIV exposure, but most HCPs perceive them as low risk for HIV infection, which delays testing. A late diagnosis of HIV leads to delayed initiation of ART. A recent study showed that almost 50% of adults over 50 were diagnosed late (CD4 cell count <200 cells/μL), and many had an AIDS-defining illness at or within three months of diagnosis. Adults over 50 who are diagnosed late are 14 times more likely to die within the first year after diagnosis (Greene, 2024; HHS, 2024a).

Surveillance and Monitoring of HIV