About this course:

This learning activity aims to increase advanced practice registered nurses' (APRNs’) understanding of osteoporosis, including the risk factors, clinical criteria for diagnosis, nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatment options, and a summary of evidence-based prevention and screening guidelines to improve patient outcomes. This paper uses the terms “female” and “male” to refer to individuals based on their biological sex, while acknowledging that this also includes those who were assigned female or male at birth regardless of their current gender identity.

Course preview

The Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Osteoporosis

This learning activity aims to increase advanced practice registered nurses' (APRNs’) understanding of osteoporosis, including the risk factors, clinical criteria for diagnosis, nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatment options, and a summary of evidence-based prevention and screening guidelines to improve patient outcomes. This paper uses the terms “female” and “male” to refer to individuals based on their biological sex, while acknowledging that this also includes those who were assigned female or male at birth regardless of their current gender identity.

This activity is designed to allow learners to:

- describe the epidemiology and pathophysiology of osteoporosis

- identify demographic and clinical risk factors for the development of osteoporosis, including the most common medications that promote bone loss

- explain evidence-based screening guidelines and identify the clinical criteria indicative of a diagnosis of osteoporosis according to the World Health Organization (WHO)

- classify the pharmacological treatment options and potential side effects and explain the principles for initiating pharmacological therapy

- compare nonpharmacological interventions to prevent and reduce the risk of osteoporosis

- summarize the core components of patient education geared toward maintaining healthy bones, preventing bone loss, and counseling points for patients receiving pharmacological therapies

Osteoporosis is a chronic, systemic disease characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD), weakening of the bones, and deterioration of bone tissue and architecture. Osteoporotic bones are brittle and porous, heightening the risk of fracture. It is referred to as a silent disease because bone loss is not painful and there are generally no warning signs or symptoms preceding a fracture. Most people do not know they have osteoporosis until they develop an acute fracture, which is the hallmark of the disease. Fractures can occur in any bone within the body, but most commonly occur in the hip bones, vertebrae, and wrists (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases [NIAMS], 2022, 2025). Low bone mass (previously osteopenia), the precursor to osteoporosis, is characterized by decreased BMD that is not severe enough to meet the criteria for osteoporosis. People with low bone mass are at a higher risk of developing osteoporosis, but when the condition is identified early and treated, a progression to osteoporotic fractures can be averted (Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Rosen & Lewiecki, 2025). The bone mass parameters for osteoporosis and low bone mass are calculated using a T-score based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III mean BMD for non-Hispanic White females between the ages of 10 and 40 of 0.885 g/cm2. It has been proposed to update the parameters with more current NHANES data to 0.888 g/cm2 (Xue et al., 2021).

Osteoporosis is the most common bone disease in the United States. However, it is manageable when proper screening and treatment guidelines are followed. Osteoporosis contributes to significant morbidity and mortality and is costly to the US health care system. Despite the high prevalence of this condition, nearly 80% of older adults are not tested or treated for osteoporosis (Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation [BHOF], n.d.). APRNs practice at the forefront of primary care across clinical settings, providing preventative care services to the public. Therefore, APRNs must acquire a proper understanding and keen awareness of osteoporosis prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment modalities to reduce morbidity and enhance patient outcomes (American Nurses Association, n.d.).

Epidemiology

Osteoporosis affects more than 10 million individuals aged 50 or over in the United States. Of these, 8 million are females, and 2 million are males. An additional 43 million people in the United States are at risk of osteoporosis due to low bone mass. Osteoporosis affects almost 20% (1 in 5) of females aged 50 and older and about 5% (1 in 20) of males aged 50 and older. The number of individuals diagnosed with osteoporosis is expected to increase by more than 30% by 2030 due to the aging US population. More than 50% (1 in 2) of females and up to 25% (1 in 4) of males with osteoporosis aged 50 and older will experience an osteoporotic-related fracture. Postmenopausal bone loss related to estrogen deficiency is a primary contributor to osteoporosis in females. Since males start with an increased bone mass, the bone loss that occurs due to age takes longer to reach the point of osteoporosis, and males are often diagnosed later in life. Therefore, females are much more likely to develop osteoporosis than males (BHOF, n.d.; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.; Sarafrazi et al., 2021; Walker & Beaman, 2022; Williams et al., 2020; Yu, 2025).

The prevalence of osteoporosis increases with advancing age. It is most prominent among females of thin build with a low body mass index (BMI) who are of European American or Asian ethnic backgrounds. Osteoporosis is less prevalent among African American males and females, but the fracture risks for those diagnosed are similar across all ethnicities. Osteoporosis is an incredibly costly disease to the US health care system, with the direct and indirect costs of osteoporotic-related fractures totaling over $57 billion. These costs are projected to rise to more than $95 billion by 2040 due to the continued growth of the aging population and the accompanying rise in annual fractures (Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Sarafrazi et al., 2021; Singer et al., 2023; Walker & Shane, 2023).

Anatomy and Physiology

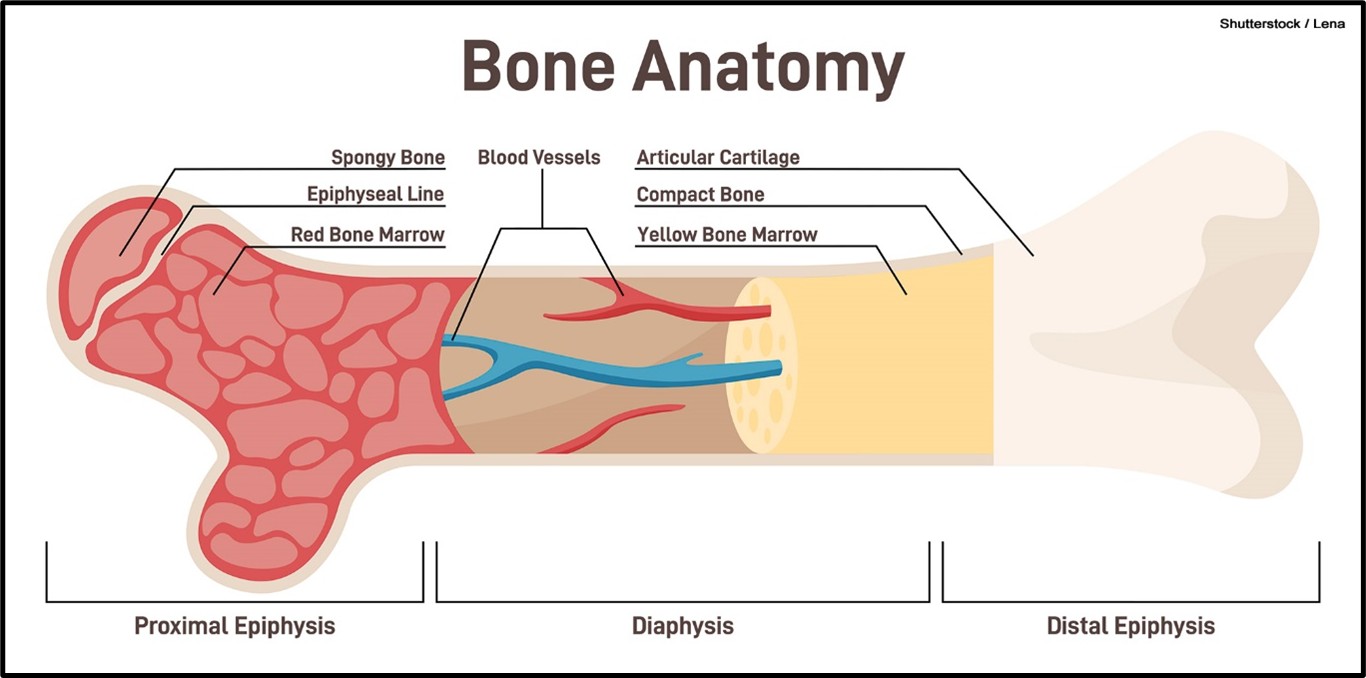

Bones are composed of nerves, blood, cartilage, connective tissue, and bony tissue. There are two main types of bone: compact and spongy. As demonstrated in Figure 1, compact bone consists of the dense, hard, outermost layer known as the cortical tissue (or cortex), which protects and strengthens the bone. In addition, it provides structural support to the body and its organs. Spongy bone is the inner layer that contains blood vessels to transport nutrients and remove waste. Spongy bone comprises many open spaces connected by trabeculae, which are thin plates of bone. Trabeculae reduce the density of bone, allowing the ends of the bones to compress from external stress or pressure and prevent fracture. Three main cell types appear within trabeculae: osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts (Rowe et al., 2023).

Figure 1

Cross Section of a Bone

Bone undergoes constant change throughout its life span. The processes of bone modeling and remodeling are necessary for bones to grow, change shape, and mature. These processes are regulated and largely dependent on the...

...purchase below to continue the course

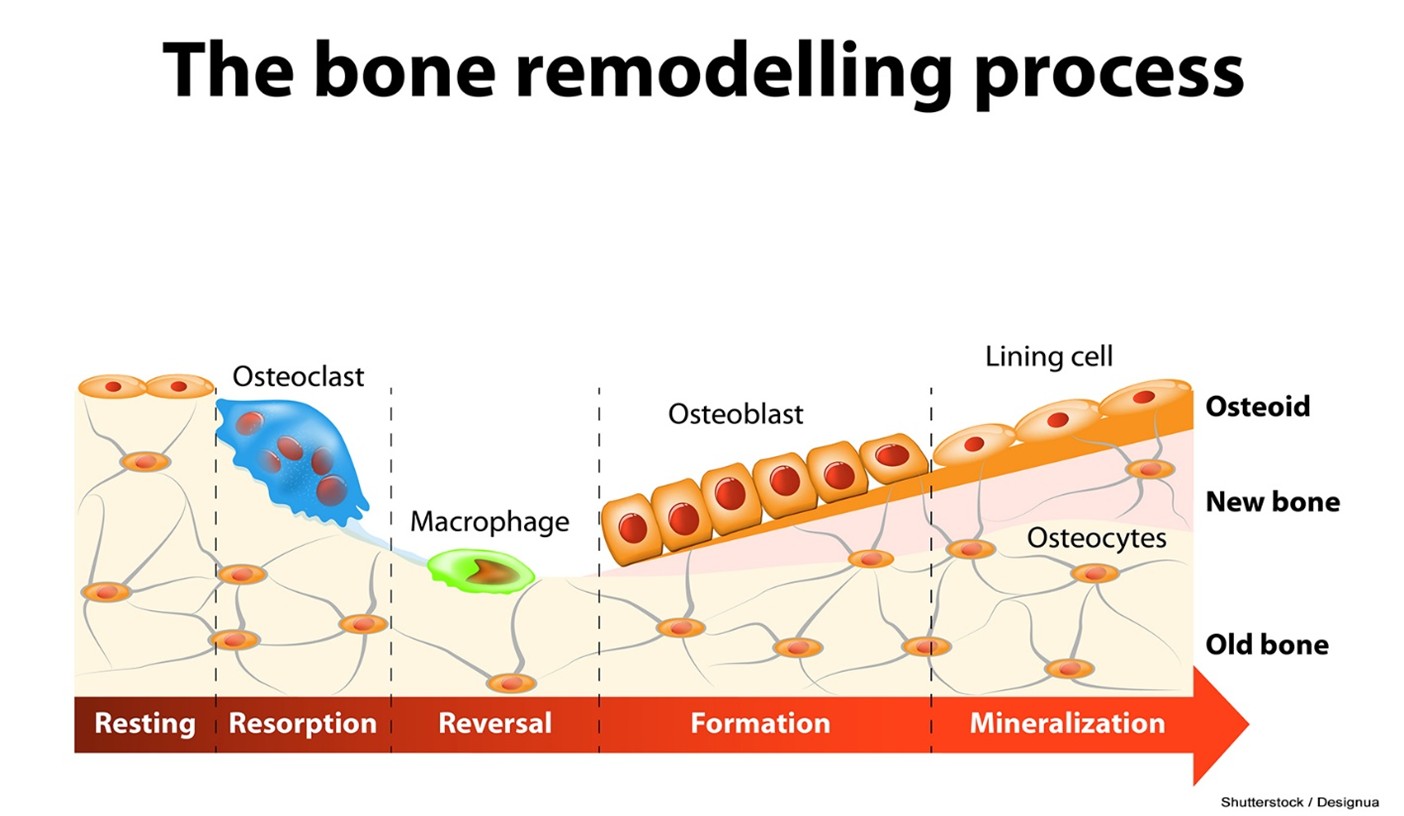

Bone modeling is the formation and shaping of bone, a process that is most prominent during infancy and childhood. During modeling, the resorption and formation of bone occur independently at various skeletal sites to generate significant changes in the bone’s architecture. Bone remodeling involves the resorption of old or damaged bone, followed by the formation and deposition of new bone material. This ongoing process occurs throughout life to maintain bone strength and mineral composition. Bone remodeling is the predominant skeletal process during adulthood, except after a bone fracture, when a significant increase in bone modeling occurs in response to the injury. Remodeling has two primary functions: (a) to repair micro-damage to maintain strength and ensure the relative youth of the skeleton, and (b) to supply calcium when needed from the skeleton to maintain serum calcium levels. Resorption and formation occur nearby during remodeling, so overall bone volume and structure remain unchanged. While bone remodeling occurs through the coordinated activity of the osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts, it is also regulated by multiple hormones, including estrogens, androgens, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and various growth factors (Lindsay & Samuels, 2022; Manolagas, 2025; Rowe et al., 2023). The process of bone remodeling is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

The Process of Bone Remodeling

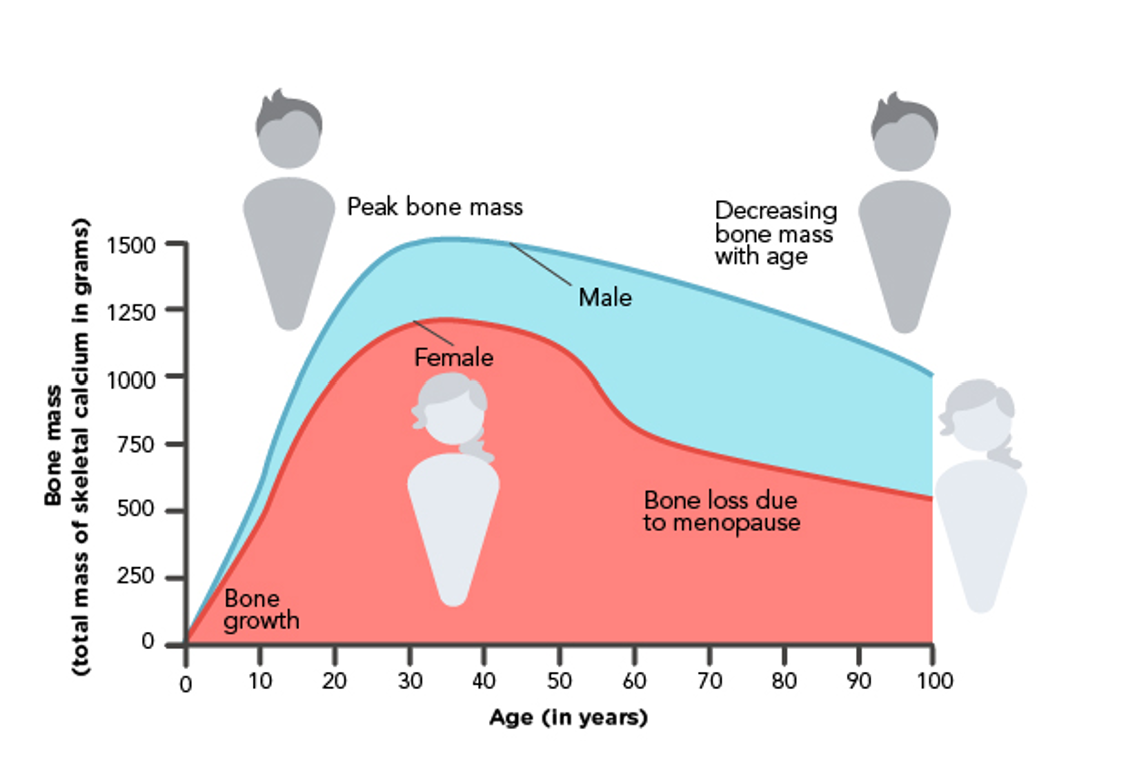

Throughout early childhood and adolescence, osteoblasts form new bone faster than they can break down the old bone. This process provides the basis for healthy, strong bones among younger age groups. The skeleton’s BMD remains relatively constant after peak bone mass is achieved around age 30. In healthy premenopausal females, bone mass is stable until perimenopause. As estrogen wanes during perimenopause, the bone-remodeling balance changes, osteoclast activity increases, and bone resorption outpaces the formation of new bone. Although estrogen does not promote bone growth, it inhibits bone loss (Manolagas, 2025; The North American Menopause Society [NAMS], 2021; Rogers & Brashers, 2023). Figure 3 provides a graphic representation of the relationship between age and bone mass in males and females.

Figure 3

Relationship Between Age and Bone Mass

Pathophysiology

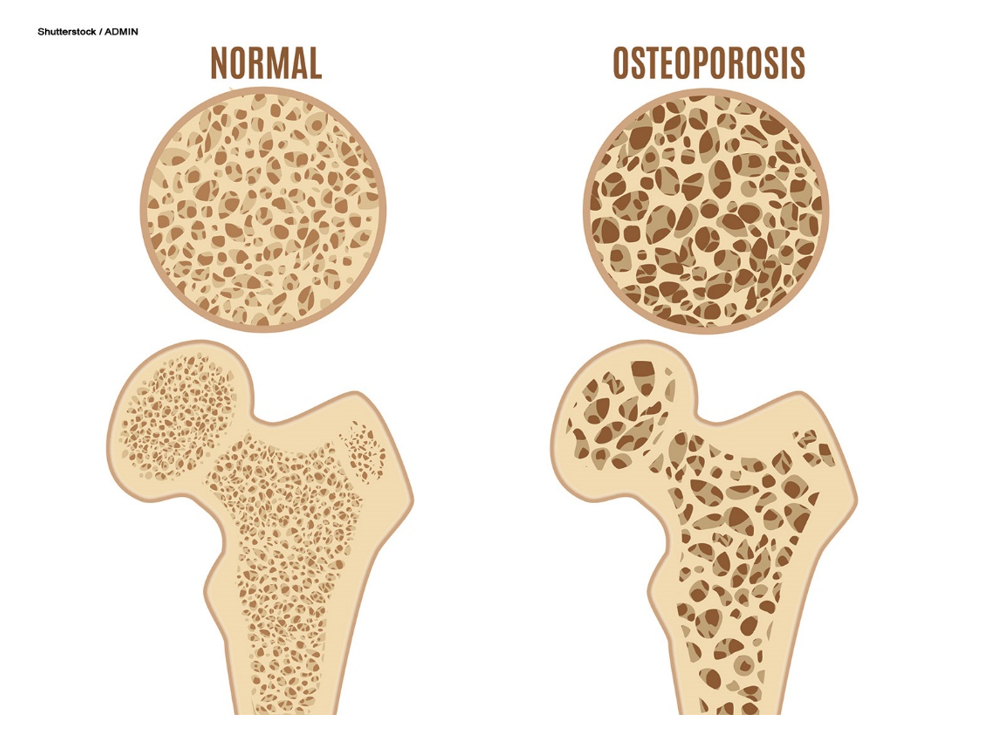

Loss of bone mass is caused by a weakening of the bony microvasculature, as the inner layer of spongy bone becomes brittle due to calcium loss. Osteoporosis affects both spongy and compact bone. It causes reduced bone density and structure of the trabecular or cancellous (spongy) bone first, followed by thinning of the cortical (compact) bone (Rogers & Brashers, 2023). The distinction between normal and osteoporotic bone is displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Normal Bone and Osteoporosis

Etiology

The etiology of bone loss and resulting osteoporosis can be primary or secondary, as various extrinsic and intrinsic factors can exaggerate the disease process. Primary osteoporosis is associated with genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. It is also related to advancing age and age-related bone loss resulting from the continual deterioration of the trabeculae over time. An imbalance in bone resorption and remodeling drives the underlying pathology. Osteoclastic activity occurs faster and more significantly than osteoblastic activity. Osteoporosis can result from failing to reach normal peak bone mass or BMD during formative years, accelerated bone loss, or a combination of both factors. Postmenopausal females experience a biological reduction of estrogen production, which fuels the progressive decline in BMD. In males, sex hormone–binding globulin inactivates testosterone and estrogen as aging occurs, contributing to BMD loss over time. Secondary osteoporosis is caused primarily by comorbid health conditions, diseases, or medications that induce an imbalance in calcium, vitamin D, or sex hormones (Dakkak et al., 2023; Finkelstein & Yu, 2025a; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023).

Risk Factors

Many risk factors and conditions can affect bone density and contribute to the development of osteoporosis. Factors that increase an individual’s risk of osteoporosis include poor nutrition, modifiable lifestyle factors, environment, genetics and family history, demographics, certain medical conditions, and medications (Lewiecki, 2024; Rogers & Brashers, 2023).

Poor Nutrition

Achieving peak bone mass may be impaired by inadequate calcium intake during growth or deficiencies in calories, protein, and minerals, leading to an increased risk of osteoporosis later in life. These factors also impact patients with a BMI below 20 kg/m2 due to inadequate caloric intake, which can be related to eating disorders (e.g., anorexia nervosa or bulimia) or a lack of access to nutrition (e.g., living in poverty). Individuals weighing under 128 lb. (58.2 kg) are at an increased risk of osteoporosis. Conversely, a BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2 has demonstrated a protective effect and a reduced risk of low bone mass and osteoporosis. Calcium is vital in maintaining bone integrity, decreasing bone turnover, and reducing bone loss. Patients with serum calcium deficiency, such as those who do not ingest enough calcium through their diet or dietary supplementation, are at risk for low bone mass and osteoporosis. Vitamin D deficiency can also result in bone disease and poor mineralization of calcium. The body will attempt to reabsorb calcium from the bone to compensate for serum calcium deficiency. When an individual’s diet lacks adequate vitamin D and calcium, the parathyroid gland is stimulated to release PTH, which promotes calcium release from the bony matrix. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is higher among malnourished patients and those with intestinal malabsorption disorders. While vitamin D deficiencies should be corrected, excessive vitamin D supplementation should be avoided. Vitamin D toxicity harms bones and promotes bone loss. Excessive caffeine intake and carbonated beverages (i.e., over 40 ounces per day) can lead to calcium loss in the urine. A diet high in phosphorus can also prompt calcium loss due to its inverse relationship. Foods high in phosphorus include beans, lentils, oats, nuts, and dairy. Increased protein intake can also lead to an increase in the amount of calcium excreted in the urine. However, in contrast to previous hypotheses, current research has shown that higher than recommended protein intake (over 0.8 g/kg body weight/day) decreases the risk of osteoporosis, bone loss, and hip fractures (ACOG, 2025; International Osteoporosis Foundation [IOF], 2025e; Lewiecki, 2024; Lindsay & Samuels, 2022; Muñoz-Garach et al., 2020; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Rondanelli et al., 2022).

Lifestyle Factors

In addition to nutrition, other lifestyle factors increase an individual’s risk for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. Although the exact mechanism is not understood, excessive alcohol consumption (i.e., more than three drinks per day) and tobacco use can lead to acidosis, which causes bone loss. Moderate alcohol consumption (1 drink or less daily), however, has been shown to have a protective effect on BMD. Excessive ingestion of alcohol is toxic to bone tissue and leads to decreased osteoblast activity and increased osteoclast activity. When alcohol is consumed excessively, malnutrition may result from a reduced intake of nutritional calories, which can exacerbate bone changes. Individuals with a sedentary lifestyle and decreased weight-bearing activity, including entirely or partially immobile individuals, have an increased risk. Geographical location can also influence risk: those living further away from the equator have a higher risk of osteoporosis due to decreased sunlight exposure (Godos et al., 2022; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023).

Demographic

Females of European or Asian descent are at the highest risk of developing osteoporosis. The risk for osteoporosis also increases with age for all genders; however, females have a greater risk for osteoporosis than males. Several factors place females at an increased risk for developing osteoporosis (Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Yu, 2025). These include:

- lower bone mass and decreased peak bone mass; since females start with a lower peak bone mass, they are affected by bone loss in a shorter amount of time and are diagnosed younger

- longer life expectancy; males are typically diagnosed after age 70; however, since the average life expectancy of a male in the United States is 75.8, many males do not live long enough to be affected by osteoporosis

- decreased calcium absorption

- bone loss acceleration after menopause as estrogen levels decline (ACOG, 2024, 2025; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2025; Keen et al., 2025; Lewiecki, 2024; Yu, 2025)

Since the ovaries produce estrogen, which contributes to bone strength and development, bone loss occurs when ovarian function declines during perimenopause and menopause. Beginning 1 to 3 years before and 4 to 8 years after the onset of menopause, annual bone loss is 5% in the first year, followed by 1% to 1.5% in the following years, leading to a BMD decrease of 10% to 12% in the spine and hips. After the menopause transition is complete, bone loss returns to an average annual rate of 0.5%. Accelerated bone loss may occur if the ovaries are surgically removed or their activity is suppressed by chemical-induced menopause (e.g., medications). On average, females will lose approximately 30% of their peak bone mass by the time they reach the age of 80. While the prevention of expected bone loss is possible with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) during natural menopause, HRT is controversial due to its increased risk of estrogen-based cancers (e.g., breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers). Therefore, HRT is contraindicated for many females (ACOG, 2024, 2025; Karlamangla et al., 2021; Keen et al., 2025; Moilanen et al., 2021; Walker & Shane, 2023).

Genetic/Hereditary Factors

Evidence suggests that genetics strongly influences osteoporosis development, with an estimated heritability between 60% and 80%. There are multiple suspected genetic changes responsible for osteoporosis, but no genetic alteration is considered more influential than any other. For some patients, osteoporosis is related to alterations in the vitamin D3 receptor (VDR) gene or the calcitonin receptor (CTR) gene. When these genes are altered, the receptor sites can no longer uptake vitamin D3 or calcitonin. Other patients have a modified bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) gene, which is instrumental in bone formation and maintenance (Keen et al., 2025; Rogers & Brashers, 2023). Family history can indicate an increased risk of developing osteoporosis, including:

- personal history of a fracture

- history of hip fracture in a biological parent (especially mother), which is associated with a twofold increased risk of hip fracture in females, regardless of BMD

- family history of osteoporosis, as peak bone mass is often lower among individuals with a family history of osteoporosis (Keen et al., 2025; Lewiecki, 2025a; Lindsay & Samuels, 2022; Porter & Varacallo, 2023)

Medical Conditions

Certain medical conditions increase an individual’s risk of osteoporosis due to accelerated bone loss. This is either a direct effect of the disease course or an adverse effect of the medication management related to the disease (Lewiecki, 2024; Rogers & Brashers, 2023). Some of the most common health conditions known to increase the risk of osteoporosis include:

- chronic illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease

- cancer and cancer treatment, particularly:

- breast cancer

- prostate cancer

- leukemia

- lymphoma

- multiple myeloma

- endocrine disorders

- insulin-dependent and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

- hyperparathyroidism

- hyperthyroidism

- Cushing’s syndrome (hypercortisolemia, which accelerates bone loss through excess glucocorticoid production)

- growth hormone deficiency

- thyrotoxicosis

- vitamin D deficiency

- hormonal disorders

- irregular menstrual cycles

- premature menopause

- low levels of testosterone and estrogen in males and females

- hypogonadism in males

- late-onset menstruation

- Gaucher disease

- neurological disorders

- stroke

- Parkinson’s disease

- multiple sclerosis

- gastrointestinal disorders

- inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- weight loss surgery such as gastric bypass or adjustable gastric band

- celiac disease

- psychiatric disorders

- eating disorders

- Other conditions

- AIDS or HIV

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including emphysema

- female athlete triad disorder, consisting of a loss of menstruation, the presence of an eating disorder, and excessive exercise

- chronic kidney disease

- liver disease, including biliary cirrhosis

- organ transplantation

- scoliosis (American College Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2025; Diffenderfer et al., 2023; Keen et al., 2025; Lewiecki, 2024, 2025a; NIAMS, 2022; Rogers & Brashers, 2023)

Medications

Medications can be detrimental to the bones, even when required to treat other conditions. For example, corticosteroids are crucial in treating various inflammatory conditions, such as asthma, IBD (i.e., ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease), COPD, and allergies. They are also used alongside other medicines to treat cancer and autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Glucocorticoids and corticosteroids are considered the most common cause of medication-induced osteoporosis. They work similarly to certain innate hormones and have significant anti-inflammatory effects on various organ systems. In addition, they induce profound and varied metabolic effects and modify the body’s immune response to stimuli. BMD declines rapidly within only 3 to 6 months of starting steroid therapy at a dose greater than or equal to 5 mg of prednisone (Deltasone) or equivalent per day. When administered over extended periods and at higher doses, steroids significantly impact bone loss and the development of severe osteoporosis. Steroids can also be used as replacement therapy for patients with adrenocortical deficiency (Lewiecki, 2024; Lindsay & Samuels, 2022; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023).

In addition to steroids, several other medications are associated with bone loss. These medications belong to different drug classes and are utilized to treat various medical conditions (Dakkak et al., 2023; Lewiecki, 2024; Lindsay & Samuels, 2022; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023). Some of the most common drugs that increase an individual’s risk of osteoporosis include:

- excessive doses of thyroid hormone

- aluminum-containing antacids such as calcium carbonate (Tums)

- immunosuppressants such as tacrolimus (Prograf) and cyclosporine (Gengraf)

- proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) such as esomeprazole (Nexium), omeprazole (Prilosec), and lansoprazole (Prevacid)

- many types of cytotoxic drugs (chemotherapy)

- some types of anticonvulsants, such as phenytoin (Dilantin) and phenobarbital (Luminal)

- heparin

- lithium (Lithobid)

- medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera)

- methotrexate (Trexall)

- thiazolidinediones, including pioglitazone (Actos) and rosiglitazone (Avandia)

- hormonal-blocking therapies:

- aromatase inhibitors such as anastrozole (Arimidex), letrozole (Femara), and exemestane (Aromasin)

- gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) medications such as leuprolide acetate (Lupron) and goserelin (Zoladex)

- tamoxifen (Nolvadex), when used in premenopausal females

- androgen deprivation therapies such as flutamide (Eulexin), bicalutamide (Casodex), or nilutamide (Anandron; Dakkak et al., 2023; Lewiecki, 2024; Lindsay & Samuels, 2022; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Rosen, 2025c; Smith, 2025)

Risk Reduction and Prevention

Many interventions can keep bones healthy and strong to prevent osteoporosis. Adequate calcium intake and physical activity during adolescence and young adulthood are essential aspects of prevention. Building strong bones during childhood and adolescence helps prevent osteoporosis later in life. Table 1 outlines the critical patient counseling points on reducing the risk of falls, as falls significantly heighten the risk of bony fractures. Clinical issues that increase fall risk of patients with osteoporosis include difficulty with balance or gait, orthostatic hypotension, lower extremity weakness, poor vision or hearing, and cognitive impairment (Camacho et al., 2020; Kiel, 2025; NIAMS, 2025).

Table 1

Strategies to Avoid Bone Fractures as a Result of Falls

Remove throw rugs and other tripping hazards, or anchor rugs to the ground |

Wear shoes with nonslip soles |

Take extreme caution when ambulating on icy, wet, or polished surfaces |

Use a cane or walker, as needed, for stabilization and support |

Add grab bars inside and outside of the tub or shower and next to the toilet |

Put railings on both sides of the stairs or in long hallways |

Keep homes well lit by adding more lamps or brighter light bulbs |

(ACOG, 2024; Camacho et al., 2020; Kiel, 2025)

Complications

Osteoporotic fractures occur due to the structural changes to the bone that accompany osteoporosis. Locations commonly affected by osteoporotic fractures include the hips, spine, and wrists. The spine and hips account for 42% of all osteoporotic fractures. Globally, approximately 37 million osteoporotic fractures occur each year, equating to 70 fractures occurring every second; however, this number may be much larger, as many fractures occur undetected. Individuals who live closer to the equator with increased exposure to sunlight—and, therefore, vitamin D—have a lower rate of osteoporotic fractures. Over 50% of postmenopausal non–Hispanic White females will experience a fracture due to osteoporosis. Of those over 65, only 33% will be able to continue living independently. Over two-thirds of fractures related to osteoporosis occur in females. As the US population ages, the number of osteoporotic fractures treated per year is expected to triple. The fracture rate is 20% for non-Hispanic White males; however, although the hip fracture rate in males is approximately one-third the rate in females of the same age, the one-year mortality rate for males is twice that of females. Males who experience an osteoporotic fracture have a 1-year mortality rate that is twice that of non-Hispanic White females (Dakkak et al., 2023; Hansen et al., 2021; Keen et al., 2025; Lewiecki, 2025a; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Yu, 2025).

Hip fracture rates are used as a proxy measure (an indirect measure of the desired outcome) for osteoporosis, as it is among the most severe fall injuries. Approximately 1.5 million people sustain a fragility fracture annually in the United States. Females experience 75% of all hip fractures related to osteoporosis. Hip fractures are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, a decreased quality of life, and a loss of independence. Most people cannot live independently following a hip fracture due to physical disability, impaired mobility, and chronic pain. Osteoporotic fractures account for $57 billion in health care spending and economic loss or indirect costs due to decreased productivity. The cost of osteoporotic fractures is expected to increase to at least $95 billion by 2040. Subsequent fractures also increase health care spending. An estimated 14% of individuals with an osteoporotic fracture will experience a secondary fracture within 12 months. The treatment of subsequent fractures accounts for $5.3 billion in Medicare spending. Preventing subsequent fractures in only 5% to 20% of individuals equates to a cost savings of between $250 million and $990 million (Clynes et al., 2020; Hansen et al., 2021; Keen et al., 2025).

Diagnostic Workup

A thorough history, medical evaluation, and laboratory assessment are vital to identify risk factors and estimate the risk of potential fracture. Providers should perform a comprehensive medical history, evaluating for current or prior use of medications that promote bone loss. In addition, it is crucial to assess for nutritional deficiencies by asking about the patient’s diet, dietary supplementation use, access to food, and other contributing factors. Activity level, lifestyle habits, exercise patterns, and alcohol or tobacco use should also be assessed. Some patients may have evidence of height loss due to compression fractures of the vertebral bodies. Other tests that may be used to evaluate bone health but that are not used to diagnose osteoporosis include biochemical marker tests, x-rays, vertebral fracture assessments (VFAs), and bone scans (Camacho et al., 2020; Rondanelli et al., 2022; Rosen & Lewiecki, 2025).

Screening

Since patients with osteoporosis are generally asymptomatic, screening is critical to identify at-risk patients. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF, 2025) recommendations have recently been updated and recommend routine osteoporosis screening with bone measurement testing for females 65 years and older and postmenopausal females younger than 65 at increased risk of osteoporosis. For postmenopausal females younger than 65 with at least one risk factor, the USPSTF recommends using a clinical risk assessment tool to determine whether they should be screened with bone measurement testing. Regarding males, the USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for osteoporosis; however, the Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation recommends BMD testing for all males 70 years of age and older and males aged 50 through 69 years based on the presence of risk factors (Hansen et al., 2021; USPSTF, 2025).

Clinical risk should be evaluated using a standard clinical risk assessment tool. Many tools are available, such as the Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE), the Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI), or the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST). These tools are considered moderately accurate at predicting osteoporosis risk. The ORAI is a validated tool developed by WHO that provides a 10-year probability of a significant fracture. It is helpful for both males and females. It considers the individual’s BMI, certain risk factors, and some causes of secondary osteoporosis. The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) estimates a patient’s 10-year probability of a hip fracture when a dual/energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) bone density test is unknown or not performed (Lewiecki, 2025a; USPSTF, 2025).

Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry

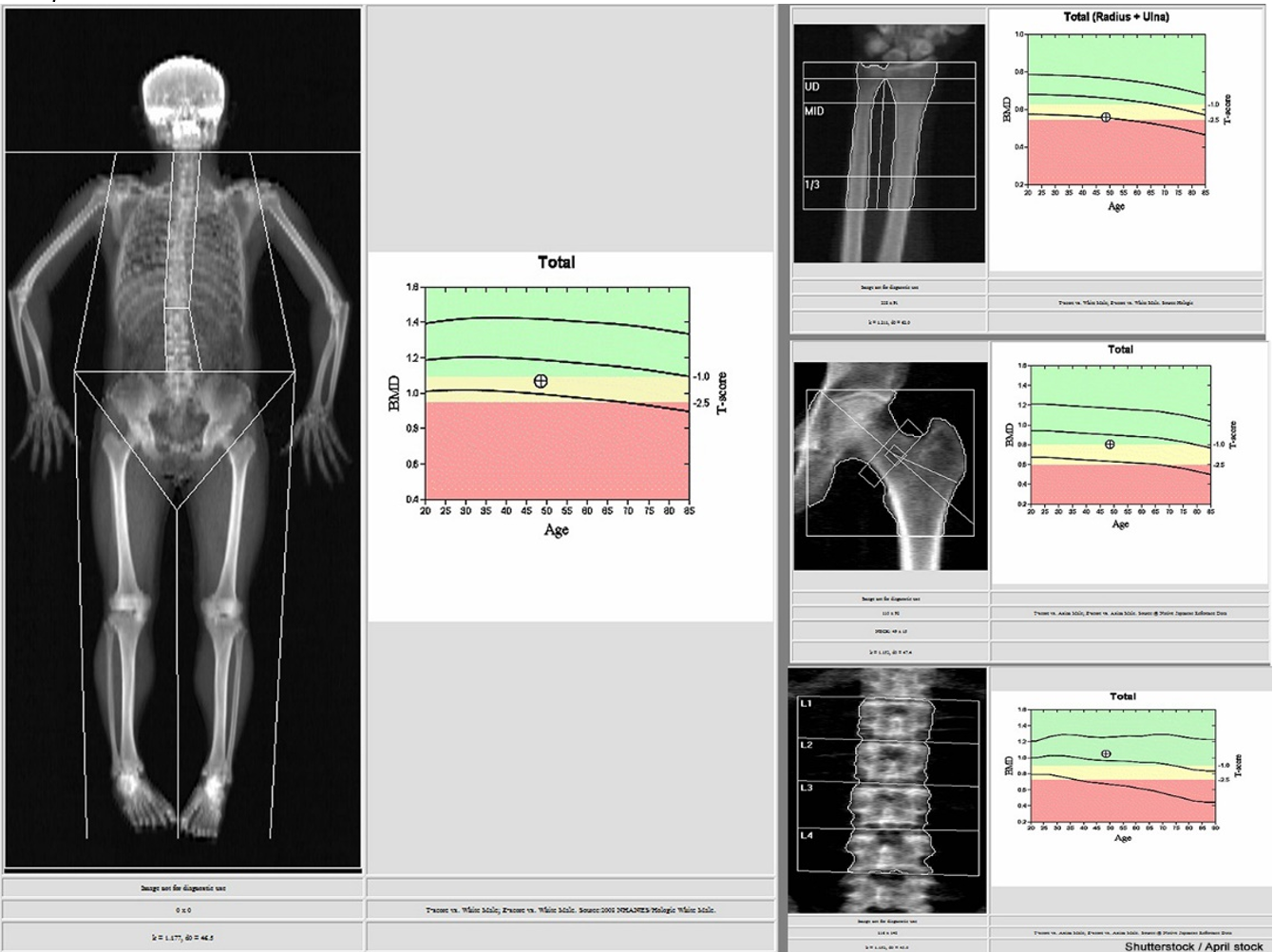

According to the WHO, the gold standard bone density test is a DXA scan of the central skeleton, which includes the hip and lumbar spine. A DXA scan is a low-level radiographic test that measures a patient’s BMD to diagnose low bone mass or osteoporosis and assess fracture risk. BMD is most commonly measured at the spine, hip, and wrist levels. The degree of bone loss is calculated and classified according to defined diagnostic criteria (Lewiecki, 2025b). The DXA scan is quick, noninvasive, and painless. As demonstrated in Figure 5, the patient is instructed to lie or sit down for under 10 minutes while the machine scans the body. The test exposes the patient to a small amount of radiation, less than the amount associated with a chest X-ray. A quantitative ultrasound (QUS) is another test that may be used for osteoporosis diagnosis. While QUS is considered a low-cost and readily accessible alternative to DXA, it measures density in bones that are not at high risk and does not correlate well with standard DXA scan results. Data is still limited on its accuracy, as the vast majority of osteoporosis literature and clinical research is premised on the DXA scan. Therefore, it is less useful in diagnosis or treatment decisions and is not utilized widely in clinical practice (ACOG, 2025; Expert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging et al., 2022; Porter & Varacallo, 2023).

Figure 5

DXA Bone Density Scan

DXA Results Interpretation

DXA test results are reported as a T-score for each site measured, comparing the patient’s BMD level to that of a healthy young adult with ethnicity- and gender-matched controls. The WHO separates those T-scores into four categories: normal, low bone mass, osteoporosis, and severe or established osteoporosis. A T-score of 0 indicates that the BMD is equal to that of a healthy young adult, a negative T-score indicates that the bones are thinner than average, and a positive T-score denotes that the bones are stronger than average. The difference between a patient’s BMD and the normal range is measured in units referred to as standard deviations. The more standard deviations below 0, denoted by negative numbers, the lower the BMD, the more severe the osteoporosis, and the higher the fracture risk. The WHO classifies osteoporosis as a BMD that is 2.5 standard deviations below normal. Treatment is usually recommended to prevent fractures when the T-score is -2.5 or lower. Table 2 defines T-scores and their corresponding BMD level (Camacho et al., 2020; Expert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging et al., 2022; NIAMS, 2025). Figure 6 shows an example DXA result report for a patient.

Table 2

WHO T-Score Interpretation

T-Score | Interpretation |

≥ -1.0 | Normal bone |

-1.0 to -2.5 | Low bone mass |

≤ -2.5 | Osteoporosis |

≤ -2.5, plus 1 or more osteoporotic fractures | Severe or established osteoporosis |

(Camacho et al., 2020; NIAMS, 2025)

Figure 6

Sample DXA Scan Results

Once low bone mass or osteoporosis has been identified, the patient should undergo specific testing, including laboratory evaluation of their renal and thyroid function, as well as serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, magnesium, and calcium levels. Hypocalcemia is a prominent manifestation of magnesium deficiency, as magnesium is required to mobilize calcium from the bone. Therefore, these patients need magnesium replacement therapy and calcium supplementation. A laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), intact PTH, phosphate, and a 24-hour urine collection for calcium, sodium, and creatinine measurement. For patients receiving thyroid hormone or with concern for a thyroid disorder, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) should also be measured. Testosterone should be evaluated in males. Celiac antibodies should be evaluated in patients with clinical suspicion of a malabsorption disorder. For patients with suspected multiple myeloma, serum and urine protein electrophoresis testing should be considered (Camacho et al., 2020; Finkelstein & Yu, 2025a).

Laboratory monitoring of bone turnover markers can provide information regarding the formation and resorption of bone. These markers can be used to detect bone changes early or monitor the effectiveness of treatment (Camacho et al., 2020). Examples of serum and urinary bone turnover markers include:

- osteocalcin (BGP)

- bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP)

- urinary collagen type 1 cross-linked C-telopeptide (s-CTX)

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)

- procollagen type 1 amino-terminal peptide (P1NP)

- total urine pyridinoline (Pyr)

- urine free deoxypyridinoline (DPyr; Camacho et al., 2020)

Management

The treatment of osteoporosis is aimed at preventing fractures, improving bone density, and reducing morbidity and mortality. These can be achieved by increasing bone mass at maturity, preventing subsequent bone loss, or restoring BMD following bone loss. The importance of nonpharmacological methods to prevent and manage the disease should be emphasized, as outlined in Table 3.

Table 3

Strategies to Prevent and Treat Low Bone Mass and Osteoporosis

Weight-bearing physical activity and exercises geared toward improving balance and strength training |

Smoking cessation counseling and referrals |

Limiting alcohol and caffeine consumption |

Fall-prevention techniques

|

Consume a well-balanced diet |

Adequate calcium and vitamin D3 are recommended for all patients

|

(ACOG, 2025; Camacho et al., 2020; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Rosen, 2025b; Rosen & Lewiecki, 2025)

Pharmacological Treatment

The primary objective of pharmacological treatment is to slow the progression of bone loss in those with low bone mass to prevent osteoporosis. For osteoporosis, the goal is to reduce the risk of fracture. Treatment recommendations are based on specific patient characteristics, such as gender, degree of fracture risk, comorbid diseases, medications, and disease severity. There is strong evidence that drug therapies provide at least a moderate benefit in reducing fractures among postmenopausal females with osteoporosis. Patients with a T-score of -2.5 or lower in the spine, femoral neck, total hip, or radius should be offered pharmacological treatment (Camacho et al., 2020; Dakkak et al., 2023; Porter & Varacallo, 2023). The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) provide evidence-based guidelines and recommendations for the management of osteoporosis; they strongly recommend pharmacologic therapy for patients who meet any of the following criteria:

- low bone mass, with a history of at least one fragility fracture in the hip or spine

- T-score of –2.5 or lower in the spine, femoral neck, total hip, or 33% of the radius

- T-score between –1.0 and –2.5 if the FRAX or trabecular bone score (TBS)-adjusted FRAX 10-year probability for major osteoporotic fracture is at least 20% or the 10-year probability of hip fracture is at least 3% (Camacho et al., 2020)

Pharmacological interventions include both dietary supplementation and prescription medications. Medications that improve BMD and decrease fracture risk in patients with osteoporosis may be used to prevent or treat the condition. Calcium, vitamin D, and magnesium deficiency should be corrected first with replacement therapy. Medications to treat osteoporosis are categorized as either antiresorptive or anabolic. Antiresorptive drugs decrease the rate of bone resorption, while anabolic medications increase bone formation. Medications that decrease bone resorption include bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as raloxifene (Evista), estrogens, calcitonin, and a newer class of drugs known as receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) inhibitors such as denosumab (Prolia). Several of these medications have overlapping indications for osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Some anabolic agents include teriparatide (Forteo), romosozumab-aqqg (Evenity), and abaloparatide (Tymlos; Camacho et al., 2020; Lindsay & Samuels, 2022; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Rosen & Lewiecki, 2025).

Patients with lower or moderate fracture risk, such as younger postmenopausal females with no prior fractures and only moderately low T-scores, should initially be started on oral agents. Combination therapy is not advised due to limited evidence on the efficacy of combining medications and the heightened potential for increased toxicities, adverse effects, and cost. Injectable agents such as teriparatide (Forteo), denosumab (Prolia), or zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa) can be used as initial therapy for patients at high risk of fracture. Indicators of a high fracture risk include advanced age, frailty, glucocorticoid use, a low T-score, a history of hip or multiple vertebral fractures, and increased fall risk. Patients who may also benefit from injectable medications include those who cannot tolerate the gastrointestinal (GI) side effects commonly associated with oral bisphosphonate therapy (see Table 4). Patients with dementia or difficulty remembering to take their medications may also benefit from injectable alternatives (Lindsay & Samuels, 2022; Rosen & Lewiecki, 2025).

The 2020 AACE/ACE clinical practice guidelines list four medications as having evidence for “broad-spectrum” antifracture efficacy in terms of vertebral, hip, and nonvertebral fracture risk reduction (Camacho et al., 2020). These medications are:

- alendronate (Fosamax), a bisphosphonate

- risedronate (Actonel), a bisphosphonate

- zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa), a bisphosphonate

- denosumab (Prolia), a RANKL inhibitor (Camacho et al., 2020)

These medications are recommended as first-line options for patients with moderate fracture risk with no prior fragility fractures and those at high fracture risk who have experienced a previous fracture (NAMS, 2021).

Bisphosphonate Therapy

Bisphosphonates are the most widely used medications for treating osteoporosis. They inhibit the action of osteoclast cells, decreasing bone turnover and increasing bone density. As listed in Table 4, there are four main bisphosphonates used for osteoporosis: alendronate (Fosamax), ibandronate (Boniva), risedronate (Actonel), and zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa). The indications for the four available bisphosphonates vary slightly based on their target site, which may guide providers when selecting the most appropriate agent to prescribe. For example, alendronate (Fosamax) has been shown to reduce the rate of hip, vertebral, and wrist fractures by almost 50%, whereas risedronate (Actonel) reduces vertebral and nonvertebral fractures by 41% over 3 years. In addition, zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa) reduces the rate of vertebral fractures by 70% and hip fractures by 40% over 3 years (Arcangelo et al., 2022; Camacho et al., 2020; IOF, 2025b; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rogers & Brashers, 2023; Rosen, 2025a).

Before initiating bisphosphonate therapy, patients must be fully educated on the potential risks and the importance of monitoring and reporting side effects. APRNs Nurses should educate patients on minimizing the adverse effects of oral therapies, such as reducing esophageal irritation by taking the medication with a full glass of water and not lying down for at least 30 minutes after taking the drug (Arcangelo et al., 2022; IOF, 2025b; Rosen, 2025a, 2025d; Woods, 2023). The most critical patient education points are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4

Bisphosphonate Treatment for Osteoporosis

Drug | Alendronate (Fosamax) | Ibandronate (Boniva) | Risedronate (Actonel) | Zoledronic Acid (Reclast, Zometa) |

Standard Treatment Dosing | 10 mg tablet PO daily or 70 mg tablet PO weekly

*Fosamax is also available as a liquid | 150 mg tablet PO monthly

*Boniva is also available in IV form, dosed at 3 mg IV every 3 months | 5 mg PO daily or 35 mg tablet PO weekly or 150 mg PO monthly | 5 mg IV over 15 minutes yearly |

Prevention Dosing | 5 mg PO daily or 35 mg po weekly | 150 mg PO monthly | 5 mg PO daily or 35 mg PO weekly or 150 mg PO monthly | 5 mg IV every other year or 5 mg IV once |

Route | Oral | Oral or IV | Oral | IV |

Dosing Instructions | The medication must be taken with at least 6–8 oz of water and on an empty stomach. The patient should be instructed to sit upright and avoid lying down for at least 30 minutes after taking the medication (at least 60 minutes for ibandronate [Boniva]). | Before administration, patients must be well hydrated. Laboratory values (serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, and calcium level) should be checked. | ||

Common Adverse Reactions | Abdominal pain, acid reflux, constipation, diarrhea, dyspepsia, musculoskeletal pain, nausea | Hypertension, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, pain in an extremity, arthralgia, back pain, diarrhea, myalgia, headaches | Hypertension, back pain, arthralgia, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, rare risk of hypersensitivity reactions | Flu-like illnesses, fever, myalgias, headaches, arthralgias, pain in an extremity, hypertension, rare eye inflammation, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea |

Warnings | Severe irritation of the upper GI tract with oral administration, medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ), atypical femur fracture (AFF) | MRONJ, AFF | ||

Contra-indications | Hypocalcemia, esophageal stricture, upper GI disease, inability to stand/sit upright for at least 30 minutes (60 minutes for Boniva) | Hypocalcemia, creatinine clearance (CrCl) below 35 mL/min | ||

Dietary | Ensure adequate daily intake of calcium 1200 mg (in divided doses) and vitamin D 800–1000 IU | |||

(Arcangelo et al., 2022; Camacho et al., 2020; Rosen, 2025a, 2025d; UpToDate Lexidrug, n.d.-a, n.d.-c, n.d.-d, n.d.-f; Woods, 2023)

Atypical Femur Fracture. Prolonged use of uninterrupted bisphosphonate therapy that extends beyond 3 to 5 years places patients at higher risk for AFF. An AFF is a femoral shaft stress fracture in patients on current or prior treatment with bisphosphonate therapy. The most commonly affected areas of the femur are the subtrochanteric and diaphyseal regions along the lateral cortex (IOF, 2025f; Porter & Varacallo, 2023). According to the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, for a definitive diagnosis of AFF, the following criteria must be met:

- the fracture must be located along the femoral diaphysis

- four out of five of the following major features must be present:

- the fracture is a result of minimal or lack of trauma, such as a fall from less than or equal to a standing height

- the fracture begins in the lateral cortex and has a transverse orientation

- when the fracture is complete, it extends through both cortices and may be associated with a medial spike; when the fracture is incomplete, only the lateral cortex may be affected

- the fracture is either minimally comminuted or noncomminuted

- there is localized periosteal or endosteal thickening of the lateral cortex at the site of the fracture (IOF, 2025f; Tile & Cheung, 2020)

Before starting therapy, patients must be counseled to seek care immediately for any sudden-onset thigh discomfort. Any patient on bisphosphonate therapy who presents with thigh discomfort should be educated to discontinue all weight-bearing activity until radiographic imaging rules out a fracture. Full-length femur and hip radiographs should be obtained, as thigh pain can indicate an impending AFF, and bisphosphonate therapy should be immediately discontinued. Patients with AFF should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon, as they often require surgical fixation. In many cases, a medullary nail is placed to provide fixation of the fracture and to allow healing. Rehabilitation programs are often necessary for those who have had a complete fracture (IOF, 2025f; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Tile & Cheung, 2020).

Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. Patients should be counseled on the potential for the severe but rare adverse effect of MRONJ that increases with prolonged use of bisphosphonate therapy. MRONJ, formerly referred to as bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ), is a chronic condition that affects the oral cavity, leading to mucosal ulceration and refractory exposure of underlying necrotic bone. The mechanism of MRONJ is still not entirely understood. However, it is likely due to a combination of factors, such as decreased bone remodeling, impaired wound healing, and an antiangiogenic effect thought to induce ischemic changes followed by necrosis. When the blood supply to the area is diminished or lost, local traumatic insult ensues with subsequent necrosis. Symptoms of MRONJ can include pain at the affected site, the presence of a periodontal pocket (e.g., abscess or infection), and numbness of the lower lip (Camacho et al., 2020; IOF, 2025f; Rosen, 2025d). The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) published an updated position paper regarding MRONJ in 2022, stating that patients may be diagnosed with MRONJ when the following criteria are met:

- current or prior treatment with bisphosphonate therapy or antiresorptive agents

- exposed bone within the oral cavity, jaw, and/or face continuously observed for longer than 8 weeks

- no prior history of metastatic disease in the jaw or radiation therapy to the jaw (Ruggiero et al., 2022)

If MRONJ is suspected, bisphosphonate therapy should be discontinued immediately and the patient referred to an oral surgeon for evaluation for possible surgical intervention. Nonsurgical management of MRONJ is aimed at improving symptoms and avoiding the progression of the condition. This may include antimicrobial mouth rinses, pain control, antibiotics, and nutritional support. Local debridement of the exposed bone may be performed for disinfection and cleaning or to reduce sharp bone edges and diminish soft tissue irritation. Before starting bisphosphonate or antiresorptive therapy, patients must be counseled on the importance of regular dental care and oral hygiene. Patients are advised to undergo routine prophylactic dental care and dental examinations every 6 months. Prevention of MRONJ is possible when adequate dental hygiene, maintenance, and treatment are performed. APRNs must also warn patients of the heightened risk of MRONJ in patients with cancer or following dental extractions or implants. Patients should be advised to alert their dentist that they are taking bisphosphonate therapy (Berenson & Stopeck, 2025; Ruggiero et al., 2022).

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs)

Some SERMs, such as raloxifene (Evista) and bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (Duavee), have estrogen activity in bone, which helps prevent bone loss, improve BMD, and decrease the risk of vertebral fracture. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (Duavee) are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to prevent postmenopausal (with intact uterus) osteoporosis only. Raloxifene (Evista) is FDA-approved to prevent and treat osteoporosis in postmenopausal females intolerant of bisphosphonates or at elevated risk for advanced breast cancer (Camacho et al., 2020; IOF, 2025d; Rosen, 2023)

Raloxifene (Evista) is a SERM that acts as an agonist to estrogen receptors on bone cells to reduce osteoclast resorption. It is prescribed as a 60 mg oral tablet taken once daily to treat or prevent postmenopausal osteoporosis. Raloxifene (Evista) is associated with a threefold increase in venous thromboembolism (VTE). Therefore, it is contraindicated in females of childbearing potential and those with a history of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or other VTE. Patients should be counseled to stop taking raloxifene (Evista) immediately and seek emergency care if they develop any of the following symptoms: hemoptysis; change in speech, vision, or coordination; pain or numbness in the chest, arm, or leg; or sudden, unexplained dyspnea. The most common side effects are milder and less severe. These include hot flashes, joint pains, nausea, dizziness, leg cramps, headaches, and increased sweating. Once the medication is stopped, the benefits are lost within 1 to 2 years (Arcangelo et al., 2022; Camacho et al., 2020; Rosen, 2023; Woods, 2023).

Denosumab (Prolia)

Denosumab (Prolia) is a fully human monoclonal antibody whose antiresorptive effects differ from bisphosphonates. It is an agonist to the receptor activator of RANKL, preventing RANKL from binding to its receptor, RANK. This process reduces the ability of precursor cells to differentiate into mature osteoclasts, decreasing the number of osteoclasts available to break down bone. Denosumab (Prolia) is considered the medication of choice for patients with renal insufficiency. Still, it is not recommended for dialysis patients or those with stage 5 kidney disease due to the high risk of hypocalcemia. For the treatment of osteoporosis, denosumab (Prolia) 60 mg is injected subcutaneously once every 6 months. Once denosumab (Prolia) therapy is initiated, discontinuation is not advised unless clinically necessary. Current research has found that prolonged therapy with denosumab (Prolia) is cost-effective with better efficacy than alendronate (Fosamax). Clinical trial data have demonstrated that if denosumab (Prolia) is stopped after 12 months of use, BMD declines to baseline values. This medication also carries a risk for MRONJ and AFF at nearly the same rates as bisphosphonate therapy (Camacho et al., 2020; IOF, 2025c; UpToDate Lexidrug, n.d.-b; Yeh et al., 2025).

Teriparatide (Forteo) and Abaloparatide (Tymlos)

Teriparatide (Forteo) and abaloparatide (Tymlos) are anabolic recombinant forms of PTH that stimulate osteoblasts to generate more bone. These drugs are not indicated for the prevention of osteoporosis. They increase bone mass in male patients with primary or hypogonadal osteoporosis at high risk for fracture. Teriparatide (Forteo) and abaloparatide (Tymlos) reduce the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal females with osteoporosis. It is also indicated for the treatment of males with a very high risk of fractures. Teriparatide (Forteo) dosing is 20 μg injected subcutaneously once daily. Abaloparatide (Tymlos) dosing is 80 μg injected subcutaneously once daily. The potential side effects of teriparatide (Forteo) and abaloparatide (Tymlos) include nausea, orthostatic hypotension, leg cramps, hypercalcemia, and hypercalciuria. A serum calcium level should be drawn approximately 16 hours after teriparatide (Forteo) is given. When treatment with anabolics is stopped, the BMD typically declines rapidly over the following year, with a more pronounced loss in females; however, fracture reduction may persist for 1 or 2 years. Currently, teriparatide (Forteo) is not recommended for use for longer than 2 years due to the risk of osteosarcoma (Camacho et al., 2020; Finkelstein & Yu, 2025b; IOF, 2025a).

Calcitonin (Miacalcin, Fortical)

Calcitonin (Miacalcin, Fortical) is a synthetic hormone approved by the FDA for the treatment of osteoporosis in females who are 5 years postmenopausal when alternative drug therapy is contraindicated or ineffective. Calcitonin slows the breakdown of bone and helps increase bone density in the spine. Limitations for using calcitonin (Miacalcin, Fortical) are related to its efficacy. It produces minimal improvements in BMD within the spine but has not demonstrated efficacy in improving BMD at other skeletal sites. Calcitonin (Miacalcin, Fortical) is available in injectable and nasal spray recombinant formulations. Calcitonin (Miacalcin, Fortical) 200 IU intranasally should be administered once daily; 100 IU can also be given subcutaneously every other day. The most common side effects of nasal calcitonin are rhinitis, epistaxis, headaches, and back pain. Injectable calcitonin is associated with hypersensitivity and injection site reactions. Some patients experience flushing of the face and hands, urinary frequency, nausea, and a skin rash (Arcangelo et al., 2022; Camacho et al., 2020; Rosen & Lewiecki, 2025).

Romosozumab-aqqg (Evenity)

Romosozumab-aqqg (Evenity) is a monoclonal anti-sclerostin antibody that the FDA approved in 2019 for treating severe osteoporosis in postmenopausal females at high risk for fracture. It should be administered in 12 monthly subcutaneous doses of 210 mg each. Adverse effects include arthralgia, headaches, insomnia, paresthesia, muscle spasms, and edema. Romosozumab-aqqg (Evenity) has a black box warning related to an increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and cardiovascular death. Therefore, it is contraindicated in patients who have suffered an MI or stroke within the last 12 months (Arcangelo et al., 2022; Woods, 2023; UpToDate Lexidrug, n.d.-e).

Treatment Duration and Follow-Up

The duration of treatment varies depending on the class of medication, the patient’s response to therapy, their tolerance, and other factors such as cost and access to treatment. However, drugs such as teriparatide (Forteo) and some different types of hormone-based therapies generally require follow-up treatment with another agent once the medication has been stopped. If not immediately followed by another treatment, bone mass is often rapidly lost. Once pharmacological therapy for osteoporosis is initiated, BMD should be evaluated with a DXA scan once every two years to monitor response (Camacho et al., 2020; Finkelstein & Yu, 2025b; Porter & Varacallo, 2023; Rosen & Lewiecki, 2025).

Nonpharmacological Interventions

APRNs should advise all patients on the importance of consuming a healthy diet that includes adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D. Patients unable to meet the daily recommended calcium and vitamin D intake through their diet should take calcium supplementation (see Table 3 for dosing recommendations). Patients with osteoporosis should be educated on the importance of low-intensity exercise. They should be instructed to engage in 120 to 300 minutes of at least moderate-intensity aerobic or weight-bearing activity each week. Weight-bearing exercise reduces the risk of hip fracture and helps build bone mass. Performing balance and muscle-strengthening activities can also help reduce the risk of falls in older adults (CDC, 2024).

Looking Forward

Recent studies have shown that for clinical and vertebral fracture prevention, bone anabolic therapies are more beneficial than bisphosphonates. This demonstrates that bone anabolic therapy use should not be restricted to patients with a significantly high risk of fracture. New therapeutic targets like Wnt pathway, inflammation, and bone cell metabolism modulators and fibroblast activation protein are on the rise, complemented by progress in drug delivery, gene therapy, and nonpharmacological treatments. Current and proposed future osteoporosis research includes:

- ensuring the long-term safety and effectiveness of new therapies, such as extending data on romosozumab (Evenity)

- conducting trials to compare the effectiveness of new agents, potential combination of agents, and determine the best sequential therapy approaches

- exploring the mechanisms behind cardiovascular safety concerns related to sclerostin and cathepsin K inhibitors

- developing and validating personalized medicine markers, such as genetic, imaging, and biomarkers, to predict response and risk

- defining the best strategies for transitioning therapies, with a focus on managing denosumab (Prolia; Ali & Kim, 2024; Händel et al., 2023; Inderjeeth & Inderjeeth, 2025; Patel & Saxena, 2025)

References

Ali, M., & Kim, Y. S. (2024). A comprehensive review and advanced biomolecule-based therapies for osteoporosis. Journal of Advanced Research, 71, 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.05.024

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2024). Osteoporosis. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/osteoporosis

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2025). Osteoporosis prevention, screening, and diagnosis: ACOG clinical practice guideline No. 1. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 138(3), 494–506. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004514

American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Advanced practice registered nurse (APRN). Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/aprn

Arcangelo, V. P., Peterson, A. M., Wilbur, V. F., & Kang, T. M. (2022). Pharmacotherapeutics for advanced practice (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Berenson, J. R., & Stopeck, A. T. (2025). Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with cancer. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/medication-related-osteonecrosis-of-the-jaw-in-patients-with-cancer

Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation. (n.d.). Osteoporosis fast facts. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Osteoporosis-Fast-Facts.pdf

Camacho, P. M., Petak, S. M., Binkley, N., Diab, D. L., Eldeiry, L. S., Farooki, A., Harris, S. T., Hurley, D. L., Kelly, J., Lewiecki, M., Pessah-Pollack, R., McClung, M., Wimalawansa, S. J., & Watts, N. B. (2020). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis—2020 update. Endocrine Practice, 26(Suppl 1), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.4158/GL-2020-0524SUPPL

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Benefits of physical activity. https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/benefits/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Life expectancy. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/life-expectancy.htm

Clynes, M. A., Harvey, N. C., Curtis, E. M., Fuggle, N. R., Dennison, E. M., & Cooper, C. (2020). The epidemiology of osteoporosis. British Medical Bulletin, 133(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa005

Dakkak, M., Banerjee, M., & White, L. (2023). Osteoporosis treatment: Updated guidelines from ACOG. American Family Physician, 108(1), 100–104. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2023/0700/practice-guidelines-osteoporosis-treatment.html

Diffenderfer, B. W., Wang, Y., Pearman, L., Pyrih, N., & Williams, S. A. (2023). Real-world management of patients with osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 31(6), e327–e335. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-22-00476

Expert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging, Yu, J. S., Krishna, N. G., Fox, M. G., Blankenbaker, D. G., Frick, M. A., Jawetz, S. T., Li, G., Reitman, C., Said, N., Stensby, J. D., Subhas, N., Tulchinsky, M., Walker, E. A., & Beaman, F. D. (2022). ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Osteoporosis and Bone Mineral Density: 2022 Update. Journal of the American College of Radiology: JACR, 19(11S), S417–S432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2022.09.007

Finkelstein, J. S., & Yu, E. W. (2025a). Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and evaluation of osteoporosis in men. UpToDate. Retrieved October 15, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-evaluation-of-osteoporosis-in-men

Finkelstein, J. S., & Yu, E. W. (2025b). Treatment of osteoporosis in men. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-osteoporosis-in-men

Godos, J., Giampieri, F., Chisari, E., Micek, A., Paladino, N., Forbes-Hernández, T. Y., Quiles, J. L., Battino, M., La Vignera, S., Musumeci, G., & Grosso, G. (2022). Alcohol consumption, bone mineral density, and risk of osteoporotic fractures: A dose-response meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031515

Händel, M. N., Cardoso, I., von Bülow, C., Rohde, J. F., Ussing, A., Nielsen, S. M., Christensen, R., Body, J. J., Brandi, M. L., Diez-Perez, A., Hadji, P., Javaid, M. K., Lems, W. F., Nogues, X., Roux, C., Minisola, S., Kurth, A., Thomas, T., Prieto-Alhambra, D., . . . Abrahamsen, B. (2023). Fracture risk reduction and safety by osteoporosis treatment compared with placebo or active comparator in postmenopausal women: Systematic review, network meta-analysis, and meta-regression analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ, 381, e068033. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-068033

Hansen, D., Pelizzari, P. M., & Pyenson, B. S. (2021). Medicare cost of osteoporotic fractures: 2021 updated report. National Osteoporosis Foundation. https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/medicare-cost-of-osteoporotic-fractures-2021-updated-report

Inderjeeth, C., & Inderjeeth, D. C. (2025). Novel therapies in osteoporosis-Clinical update–2025. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 102100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2025.102100

International Osteoporosis Foundation. (2025a). Anabolics. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/health-professionals/treatment/anabolics

International Osteoporosis Foundation. (2025b). Bisphosphonates. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/health-professionals/treatment/bisphosphonates

International Osteoporosis Foundation. (2025c). Denosumab. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/health-professionals/treatment/denosumab

International Osteoporosis Foundation. (2025d). MHT & SERM. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/health-professionals/treatment/mht-serm

International Osteoporosis Foundation. (2025e). Protein and other nutrients. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/health-professionals/prevention/nutrition/protein-and-other-nutrients

International Osteoporosis Foundation. (2025f). Side effects. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/health-professionals/treatment/side-effects

Karlamangla, A. S., Shieh, A., & Greendale, G. A. (2021). Chapter fifteen-hormones and bone loss across the menopause transition. Vitamins and Hormones, 115, 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.vh.2020.12.016

Keen, M. U., Barnett, M. J., & Anastasopoulou, C. (2025). Osteoporosis in females. StatPearls. Retrieved October 14, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559156/

Kiel, D. P. (2025). Falls in older persons: Risk factors and patient evaluation. UpToDate. Retrieved October 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/falls-in-older-persons-risk-factors-and-patient-evaluation

Lewiecki, E. M. (2024). Osteoporosis: Clinical evaluation. Endotext. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279049/

Lewiecki, E. M. (2025a). Fracture risk assessment. UpToDate. Retrieved October 15, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/fracture-risk-assessment

Lewiecki, E. M. (2025b). Overview of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-dual-energy-x-ray-absorptiometry

Lindsay, R., & Samuels, B. (2022). Osteoporosis. In J. Loscalzo, A. S. Fauci, D. L. Kasper, S. L. Hauser, D. L. Longo, & J. L. Jameson (Eds.), Harrison's principles of internal medicine (21st ed., pp. 3191–3208). McGraw-Hill Education.

Manolagas, S. C. (2025). Normal skeletal development and regulation of bone formation and resorption. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/normal-skeletal-development-and-regulation-of-bone-formation-and-resorption

Moilanen, A., Kopra, J., Anna Moilanen, Kröger, H., Sund, R., Rikkonen, T., & Sirola, J. (2021). Characteristics of long-term femoral neck bone loss in postmenopausal women: A 25-year follow-up. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 37(2), 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.4444

Muñoz-Garach, A., García-Fontana, B., & Muñoz-Torres, M. (2020). Nutrients and dietary patterns related to osteoporosis. Nutrients, 12(7), 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12071986

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2022). Osteoporosis. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/osteoporosis

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2025). Bone mineral density tests: what the numbers mean. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/bone-mineral-density-tests-what-numbers-mean

The North American Menopause Society. (2021). Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: The 2021 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause, 28(9), 973–997. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001831

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Healthy people 2030: Osteoporosis workgroup. US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/workgroups/osteoporosis-workgroup

Patel, D., & Saxena, B. (2025). Decoding osteoporosis: Understanding the disease, exploring current and new therapies and emerging targets. Journal of Orthopaedic Reports, 4(4), 100472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jorep.2024.100472

Porter, J. L., & Varacallo, M. (2023). Osteoporosis. StatPearls. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441901

Rogers, J. L., & Brashers, V. L. (Eds.). (2023). McCance and Huether's pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children (9th ed.). Elsevier.

Rondanelli, M., Faliva, M. A., Barrile, G. C., Cavioni, A., Mansueto, F., Mazzola, G., Oberto, L., Patelli, Z., Pirola, M., Tartara, A., Riva, A., Petrangolini, G., & Peroni, G. (2022). Nutrition, physical activity, and dietary supplementation to prevent bone mineral density loss: A food pyramid. Nutrients, 14(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14010074

Rosen, H. N. (2023). Selective estrogen receptor modulators for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/selective-estrogen-receptor-modulators-for-prevention-and-treatment-of-osteoporosis

Rosen, H. N. (2025a). Bisphosphonate therapy for the treatment of osteoporosis. UpToDate. Retrieved October 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bisphosphonate-therapy-for-the-treatment-of-osteoporosis

Rosen, H. N. (2025b). Calcium and vitamin D supplementation in osteoporosis. UpToDate. Retrieved October 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/calcium-and-vitamin-d-supplementation-in-osteoporosis

Rosen, H. N. (2025c). Drugs that affect bone metabolism. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/drugs-that-affect-bone-metabolism

Rosen, H. N. (2025d). Risks of bisphosphonate therapy in patients with osteoporosis. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/risks-of-bisphosphonate-therapy-in-patients-with-osteoporosis

Rosen, H. N., & Lewiecki, E. M. (2025). Overview of the management of low bone mass and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-management-of-low-bone-mass-and-osteoporosis-in-postmenopausal-women

Rowe, P., Koller, A., & Sharma, S. (2023). Physiology, bone remodeling. StatPearls. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499863

Ruggiero, S. L., Dodson, T. B., Aghaloo, T., Carlson, E. R., Ward, B. B., & Kademani, D. (2022). American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons' position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws—2022 update. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 80(5), 920–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2022.02.008

Sarafrazi, N., Wambogo, E. A., & Shepherd, J. A. (2021). Osteoporosis or low bone mass in older adults: United States, 2017–2018 (NCHS Data Brief, 405). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm

Singer, A., McClung, M. R., Tran, O., Morrow, C. D., Goldstein, S., Kagan, R., McDermott, M., & Yehoshua, A. (2023). Treatment rates and healthcare costs of patients with fragility fracture by site of care: A real-world data analysis. Archives of Osteoporosis, 18(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-023-01229-7

Smith, M. R. (2025). Side effects of androgen deprivation therapy. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/side-effects-of-androgen-deprivation-therapy

Tile, L., & Cheung, A. M. (2020). Atypical femur fractures: Current understanding and approach to management. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease, 12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X20916983

UpToDate Lexidrug. (n.d.-a). Alendronate: Drug information. UpToDate. Retrieved October 15, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/alendronate-drug-information

UpToDate Lexidrug. (n.d.-b). Denosumab (including biosimilars): Drug information. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/denosumab-including-biosimilars-drug-information

UpToDate Lexidrug. (n.d.-c). Ibandronate: Drug information. UpToDate. Retrieved October 15, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ibandronate-drug-information

UpToDate Lexidrug. (n.d.-d). Risendronate: Drug information. UpToDate. Retrieved October 15, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/risedronate-drug-information

UpToDate Lexidrug. (n.d.-e). Romosozumab: Drug information. UpToDate. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/romosozumab-drug-information

UpToDate Lexidrug. (n.d.-f). Zolendronic acid: Drug information. UpToDate. Retrieved October 15, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/zoledronic-acid-drug-information

US Preventive Services Task Force. (2025). Osteoporosis to prevent fractures: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/osteoporosis-screening

Walker, E. A., & Beaman, F. D. (2022). ACR Appropriateness Criteria® osteoporosis and bone mineral density: 2022 update. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 19(11), S417–S432. https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(22)00641-X/fulltext

Walker, M. D., & Shane, E. (2023). Postmenopausal osteoporosis. The New England Journal of Medicine, 389(21), 1979–1991. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp2307353

Williams, S. A., Daigle, S. G., Weiss, R., Wang, Y., Arora, T., & Curtis, J. R. (2020). Economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the US Medicare population. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 55(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028020970518

Woods, A. D. (2023). Nursing 2023 drug handbook (43rd ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Xue, S., Zhang, Y., Qiao, W., Zhao, Q., Guo, D., Li, B., Shen, X., Feng, L., Huang, F., Wang, N., Oumer, K. S., Getachew, C. T., & Yang, S. (2021). An updated reference for calculating bone mineral density T-scores. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 106(7), e2613–e2621. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab180

Yeh, E., Saeedian, M., & Badaracco, J. (2025). A comprehensive update on the cost-effectiveness of 10-year denosumab vs alendronate in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in the United States. Archives of Osteoporosis, 20(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-025-01564-x

Yu, E. W. (2025). Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-osteoporosis-in-postmenopausal-women-and-men

Powered by Froala Editor