This course explores the causes, prevalence, and prevention strategies for peripartum (maternal) morbidity and mortality. In addition, it reviews the differences in the peripartum mortality rate across various geographic locations and racial groups as well as the impact of implicit bias in peripartum health care.

...purchase below to continue the course

11 states had a birth rate that did not change. Sixteen states had a 1–2% decrease, and another 16 states had a 3–4% decrease. The remaining 7 states (i.e., California, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Nevada, Rhode Island, and Vermont) had an even higher decrease in birth rate (Osterman et al., 2025).

An individual’s age at the time of pregnancy can influence peripartum mortality rates. There is evidence that the peripartum mortality risk increases as the age of the pregnant individual at the time of delivery rises. In 2020, individuals younger than 25 years of age had a peripartum mortality rate of 13.8 per 100,000 births, an increase from 10.6 in 2018 and 12.6 in 2019. The mortality rate in this age group peaked at 20.4 in 2021 and then decreased to 14.4 in 2022. Those aged 25 to 39 had a rate of 22.8 per 100,000 births, an increase from 16.6 in 2018 and 19.9 in 2019. Similarly, the mortality rate in this age group peaked at 31.3 in 2021 and then decreased to 21.1 in 2022. Individuals over 40 had a peripartum mortality rate of 107.9 per 100,000 births in 2019, a significant increase from 81.9 in 2018 and 75.5 in 2019. The mortality rate in this age group also peaked at 138.5 in 2021 and then decreased to 87.1 in 2022. The peripartum mortality rate among individuals older than 40 was 6 times higher than the peripartum mortality rate among individuals under 25 years old. Over the last 22 years, individuals have been delaying pregnancy until later in life, increasing the average age at the time of delivery. In 2023, the mean age of an individual at the time of delivery was 27.5, which is the highest mean age in history. Individuals between the ages of 20 and 29 comprise 45.1% of all live births, while individuals ages 30 to 39 comprise 47%. The birth rates for 2024 by age of the female parent are outlined in Table 1 (CDC, 2025a; Hoyert, 2024; March of Dimes, 2024).

Table 1

Birth Rates by Age of the Female Parent in the United States

Age | 2024 (per 1,000 people) |

15 to 19 years old | 12.6 |

20 to 24 years old | 55.8 |

25 to 29 years old | 89.5 |

30 to 34 years old | 93.7 |

35 to 39 years old | 54.3 |

40 to 44 years old | 12.7 |

(National Center for Health Statistics, 2025)

Peripartum Mortality in the United States Versus Other Countries

Despite numerous initiatives and changes in the delivery of peripartum care, the peripartum mortality rate in the United States is higher than in other countries classified as developed and high-income or high-resource. As the peripartum morbidity and mortality rates remain high in the United States, the global rates decreased by 40% from 2000 to 2023. Despite a decline since the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States continues to have high peripartum mortality, particularly among Black patients. Table 2 outlines the differences in peripartum mortality rates between the United States and other developed, high-income countries (Douthard et al., 2021; Gunja et al., 2024; United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], 2025).

Table 2

Comparison of Peripartum Mortality Rates of Select High-Income Countries (per 100,000 births)

| 2000 | 2010 | 2017 | 2023 |

Australia | 7 | 5 | 6 | 3.5 |

Canada | 9 | 11 | 10 | 8.4 |

Netherlands | 13 | 7 | 5 | 2.8 |

United Kingdom | 10 | 10 | 7 | 5.5 |

United States | 12 | 18 | 19 | 18.7 |

(Douthard et al., 2021; Gunja et al., 2024)

Implicit Bias

Implicit bias, also known as implicit attitude or implicit prejudice, refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that unconsciously affect our actions, understanding, and decisions. These biases are activated involuntarily without individual awareness or intentional control and can include favorable and unfavorable assessments of another person. Implicit bias in reproductive health care can lead to disparities in health outcomes and health care access for underserved racial and ethnic populations. Multiple factors contribute to health disparities, including the presence of underlying chronic conditions, variations in the quality of care delivered, access to reproductive health care, structural racism, and social determinants of health (SDOH). Racial disparities are well documented in obstetrics and gynecology care. For example, Black patients have higher preterm birth rates than do their White counterparts. In addition, Black patients are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than are White patients (CDC, 2024h; Norris & Harris, 2024; Shah & Bohlen, 2023). Implicit bias also has an impact on postpartum hemorrhage. Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues (2018) conducted a retrospective cohort study of 360,000 patients who experienced postpartum hemorrhage. After adjusting for comorbidities, Black patients who experienced postpartum hemorrhage had a higher risk of severe morbidity and death than White patients (Gyamfi-Bannerman et al., 2018; Okunlola et al., 2022).

These examples highlight the health disparities and inequities among racial and ethnically diverse populations related to obstetrical and gynecological health outcomes. These differences may be partially attributed to patient-level variables such as biological factors or genetics. However, many of these differences persisted even after researchers controlled for multiple characteristics. Research has also highlighted numerous differences in the health care that individuals of diverse racial/ethnic populations receive (i.e., health screening, type of care, and level of care). Biological or genetic factors cannot explain these differences, highlighting systemic and structural barriers to care equity (Norris & Harris, 2024; Shah & Bohlen, 2023).

Determining the factors that impact the disparities in health care provided to individuals of different races and ethnicities can be challenging. These factors can include the patient, clinician, health care system, and sociocultural levels. Patient-related factors may play some role in the disparities in health outcomes or care received. For example, individuals may advocate for varying degrees of quality care based on their education level or health literacy. Next, implicit bias among clinicians can result in different levels of care provided to individuals of different racial/ethnic groups. In addition to implicit bias, clinician-patient communication may be suboptimal and culturally insensitive. Also, the health care system creates a broader structure for health and care disparities. For example, people in certain racial and ethnic groups in the United States are more likely to experience financial and insurance constraints that limit their treatment options. Finally, SDOH plays an important role in the health outcomes of individuals. For example, individuals may be labeled noncompliant with recommended treatments or medications when, in fact, barriers such as stable housing, transportation, or lack of food are significantly impacting their health choices (CDC, 2024h; Norris & Harris, 2024; Ricks et al., 2021; Shah & Bohlen, 2023).

According to SisterSong (n.d.) Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, reproductive justice is “the human right to maintain bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities” (para. 1). This organization was founded in 1997 by sixteen Women of Color, representing Native American, Latin American, African American, and Asian American communities. The reproductive justice movement differs from the reproductive rights movement of the 1970s, which many people felt only focused on the abortion debate. Instead, the reproductive justice movement focuses more broadly on how factors such as race, ethnicity, social class, disability, and sexual identity can limit patient freedom. In addition, the reproductive justice movement focuses on limiting oppressive circumstances related to informed choices about pregnancy and access to affordable, equitable care and education (i.e., contraception, prevention, and care for sexually transmitted infections [STIs], alternative birth options, domestic violence assistance, safe homes, adequate wages, and comprehensive prenatal and pregnancy care; SisterSong, n.d.).

Disparities

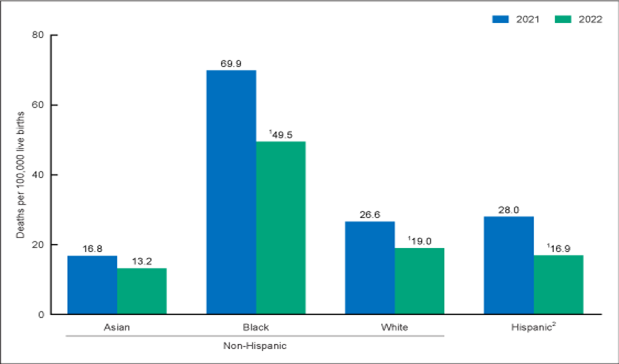

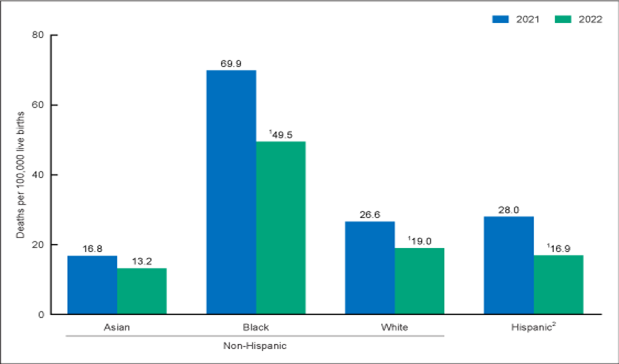

Certain groups experience peripartum mortality and morbidity at different rates than others. Hispanic individuals had the lowest peripartum mortality rates at 11.8 per 100,000 live births in 2018, 12.6 in 2019, and 18.2 in 2020. However, the 44% increase in the peripartum mortality rate among Hispanic individuals between 2019 and 2020 was the most significant increase among all racial groups. This was also the most significant increase in the mortality rate for this group since 2000, as Hispanic individuals tend to have lower peripartum mortality rates. During the COVID-19 pandemic, peripartum mortality rates among Hispanic individuals peaked at 28.0 in 2021 and then dropped to 16.9 in 2022. Asian individuals had the lowest mortality rates in 2021 (16.8 per 100,000 live births), decreasing to 13.2 per 100,000 live births in 2022. White individuals had the next lowest peripartum mortality rates, with 14.9 per 100,000 live births in 2018, 17.9 in 2019, and 19.1 in 2020. Similarly, in 2021, the mortality rate peaked at 26.6 and then decreased to 19.0 per 100,000 live births. Black individuals had a disproportionately elevated peripartum mortality rate compared to other racial groups. In 2018, the peripartum mortality rate for this group was 37.3 per 100,000 live births, increasing to 44.0 in 2019. In 2020, the peripartum mortality rate among Black individuals increased again to 55.3 and peaked in 2021 at 69.9. In 2022, the mortality rate among Black individuals decreased to 49.5 but remained significantly higher than that of other racial/ethnic groups. The peripartum mortality rate for Asian individuals was 13.3 per 100,000 live births in 2018 and remained steady at 13.8 in 2019 and 12.3 in 2020. The mortality rate for Asian individuals also peaked at 16.8 in 2021 before dropping to 13.2 in 2022 (refer to Figure 1). This difference in mortality rates between racial groups may be a result of an individual’s ability to access quality prenatal and postpartum care, the prevalence of chronic illness among certain groups, and the presence of structural racism and implicit bias (CDC, 2024h; Hoyert, 2024).

Figure 1

Peripartum Mortality by Racial Group

(Hoyert, 2024)

SMM refers to a life-threatening event during pregnancy, delivery, or postpartum based on 21 indicators defined by the CDC. These indicators show an increased risk of the individual experiencing short- or long-term morbidity, mortality, increased hospital stays, and health care costs. There has been a rise in the number of individuals suffering from a chronic condition at the time of pregnancy diagnosis. Individuals with multiple chronic conditions during pregnancy had a 276% increased risk of SMM, and the overall rate of SMM increased from 49.5 per 10,000 in-hospital deliveries in 1993 to 144.0 in 2014. In 2021, the rate of SMM was 101.1 per 10,000 in-hospital deliveries in the United States. One contributor to this increase is the number of blood transfusions administered as a result of postpartum hemorrhage, which rose from 24.5 per 10,000 in-hospital deliveries in 1993 to 122.3 per 10,000 in-hospital deliveries in 2014. When blood transfusions are excluded from the data, the rate of SMM increased from 28.6 per 10,000 in-hospital deliveries in 1993 to 35.0 per 10,000 in-hospital deliveries in 2014, which is still a 20% increase. Numerous studies have found that Black individuals are more likely to experience SMM than White individuals (i.e., 225.7 versus 104.7 per 10,000 in hospital deliveries). Similar findings were reported for all other racial and ethnic groups compared to White individuals. In a cross-sectional analysis of a large nationwide database, Aziz and colleagues (2019) evaluated over 11.3 million births between 2012 and 2014. The researchers found that Black individuals were approximately 80% more likely to be readmitted postpartum and 16% more likely to experience an SMM during readmission than White individuals (Aziz et al., 2019; CDC, 2024g; Moroz, 2025).

There are also disparities in the peripartum mortality rate between geographical locations, especially for those living in urban versus rural communities. Utilizing the National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, data have been compiled depicting the peripartum mortality rate during pregnancy up to 1 year postpartum for different types of counties. These regions are divided into the categories of a large central metro, large fringe metro, medium metro, small metro, micropolitan, and noncore (rural) counties. Large fringe metro counties had the lowest peripartum mortality rate at 13.8 per 100,000 live births, followed by large central metro at 15.7, medium metro at 16.3, small metro at 17.9, micropolitan at 19.5, and noncore with the highest peripartum mortality rate at 24.4 per 100,000 live births. These numbers indicate the presence of a disparity in peripartum mortality rates between urban and rural counties, possibly due to limited or a lack of access to obstetrical and gynecological-specific health providers and services and the increased prevalence of chronic conditions. The presence of a chronic prepregnancy condition may contribute to a high-risk pregnancy, along with a greater distance to institutions and providers equipped to care for these individuals (Melotte, 2022; National Center for Health Statistics, 2024).

Risk Factors

Certain factors can increase an individual’s risk of peripartum morbidity and mortality. Some of these factors are modifiable, and the risk can be decreased with lifestyle changes or proper medical management. Others are nonmodifiable (Brown & Small, 2025; NICHD, 2020b). Some individuals experience peripartum morbidity or mortality without any identified risk factors or the presence of symptoms. Factors that increase an individual’s risk include:

- presence of a preexisting condition such as asthma, cardiovascular disease, BMI over 30 kg/m2, or immunodeficiency

- age over 40 at the time of pregnancy

- current or past smoking history

- multiple-gestation pregnancy

- development of preeclampsia

- gestational diabetes

- delivery via vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC)

- race

- socioeconomic status (Brown & Small, 2025; NICHD, 2020b)

A person’s lifetime risk of dying due to pregnancy is calculated using the risk that a 15-year-old individual with the ability to become pregnant will die as a result of pregnancy over their life span. It is determined using the peripartum mortality and fertility rates of the country where the individual resides. The fertility rate is the average number of births per individual over their reproductive years. Due to this, high-fertility countries have a higher mortality rate than low-fertility countries since these individuals are exposed to potential causes of peripartum mortality more frequently. Therefore, the higher the fertility rate, the higher the lifetime risk of death due to a pregnancy-related complication. The lifetime risk of peripartum mortality in Africa ranges from 1 in 28 to 1 in 58, and in South Asia, the lifetime risk is 1 in 240. In contrast, the lifetime peripartum mortality risk is 1 in 3,100 in North America and 1 in 11,900 in Western Europe (UNICEF, 2025).

Causes

There are various causes of peripartum morbidity and mortality, and many of them can overlap with the risk factors described previously. Some cases of peripartum morbidity and mortality are related to preexisting conditions that are exacerbated by pregnancy, and others occur as a direct result of pregnancy (Brown & Small, 2025; NICHD, 2020a). Causes of peripartum morbidity include:

- cardiovascular disease

- preexisting or gestational diabetes

- chronic or pregnancy-induced hypertension

- infection following delivery or as a complication of pregnancy (e.g., an untreated urinary tract infection)

- blood clot

- hemorrhage

- anemia

- persistent nausea and vomiting or hyperemesis gravidarum

- perinatal mental health disorders, including depression or anxiety (Brown & Small, 2025; NICHD, 2020a)

The WHO reports the following as the most common causes of peripartum mortality worldwide:

- hemorrhage is the leading cause of peripartum mortality globally (i.e., 27% of all peripartum deaths)

- pregnancy-induced hypertension leading to preeclampsia or eclampsia (14%)

- infection leading to sepsis (11%)

- undergoing an abortion (8%, 99% of which are due to an unsafe procedure)

- embolism (3%)

- other direct causes (e.g., complications of delivery or obstructed labor, 10%)

- indirect causes (e.g., preexisting medical conditions, HIV-related peripartum deaths, 28%; Brown & Small, 2025; NICHD, 2020a; UNICEF, 2025)

In the United States, the most common causes of peripartum mortality during pregnancy up to 1 year postpartum include:

- mental health conditions (i.e., overdose/poisoning related to substance use disorder [SUD], suicide, 22.7%)

- hemorrhage, 13.7%

- cardiovascular conditions, 12.8%

- infection, 9.2%

- embolism, 8.7%

- cardiomyopathy, 8.5%

- hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, 6.5%

- amniotic fluid embolism, 3.8%

- injury (i.e., overdose/poisoning not related to a SUD, homicide), 3.6%

- CVA, 2.5% (Brown & Small, 2025; NICHD, 2020a)

The primary causes of peripartum mortality have fluctuated over time. Mortality due to hemorrhage, pregnancy-induced hypertension leading to preeclampsia or eclampsia, or a complication related to anesthesia has decreased; however, the mortality attributed to cardiovascular disease and mental health conditions has increased. This is attributed in the United States to rising cases of diabetes, hypertension, or chronic heart disease during the population’s reproductive years. These conditions can be exacerbated by pregnancy, leading to a high-risk pregnancy with an increased risk of peripartum mortality and the need for close monitoring by HCPs (Brown & Small, 2025; CDC, 2024f).

An emerging cause of peripartum death is self-inflicted harm, either by suicide or overdose. One study in Colorado reported 211 peripartum deaths related to self-harm over 9 years. The majority of these 211 deaths occurred during the postpartum period. Of the individuals who died from self-harm in this study, approximately 50% had a documented history or positive screening indicating mental illness or SUD. A 4-year study in Philadelphia revealed that 49% of peripartum deaths were related to a nonmedical cause, including homicide, suicide, overdose, or MVA. Of the 49% of peripartum deaths attributed to nonmedical causes, 40% resulted from an overdose (Collier & Molina, 2019). In a more recent population-based study, researchers found that the rates of suicide and overdose varied across the United States, with the highest rates of suicide in Montana, Colorado, and Utah and the highest rates of drug overdose in Delaware, New Hampshire, and Ohio (Wallace & Jahn, 2025). Based on such data, researchers and HCPs are advised to consider more than medical conditions and complications when addressing peripartum mortality rates. Mental illness, substance use, and domestic violence screenings are essential tools that can be used to identify individuals at a higher risk of peripartum death due to a nonmedical cause, thereby increasing the likelihood that an individual will receive proper prenatal and postpartum treatment and intervention (CDC, 2024f; Collier & Molina, 2019).

Prevention

There are ways to prevent some of the causes of peripartum morbidity and mortality, such as implementing healthy lifestyle choices before becoming pregnant and maintaining a healthy lifestyle throughout pregnancy. Making lifestyle changes is even more crucial for those who suffer from a preexisting condition such as diabetes, BMI over 30 kg/m2, or hypertension. Examples of lifestyle changes that can improve overall health include eating whole, plant-based foods; increasing physical activity; engaging in active weight loss; and abstaining from alcohol, tobacco, and other substances. Seeing an HCP before becoming pregnant to determine any risk factors that can be mitigated, followed by routine prenatal care during pregnancy, can also decrease the risk of peripartum morbidity and mortality (CDC, 2024f).

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a position statement in 2018 that was reaffirmed in 2025, endorsed by other reproductive health organizations, calling for the acknowledgment of the importance of proper postpartum care during the fourth trimester (i.e., the 12 weeks following delivery). Medicaid is the largest payer of perinatal care services, but it covers an individual for only 60 days following delivery. Analysis of data from the National Center for Health Statistics from 1999 to 2016 demonstrated that states that expanded Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum had 1.6 fewer peripartum deaths per 100,000 individuals than those that did not expand Medicaid coverage past 60 days postpartum. As of January 2025, 49 states and DC have implemented the Medicaid extension for 12 months postpartum, with Wisconsin being the only state with limited coverage, but it has proposed the expansion (ACOG, 2018; Douthard et al., 2021; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2025).

Improving Outcomes

Numerous groups and initiatives focus on improving pregnancy outcomes and preventing peripartum morbidity and mortality. Examples of these groups and initiatives include the Hear Her campaign, the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS), Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (PQCs), CDC Levels of Care Assessment Tool (LOCATe), State Strategies for Preventing Pregnancy-Related Deaths (including Enhancing Reviews and Surveillance to Eliminate Maternal Mortality [ERASE MM]), The Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality Strategy, and Healthy People 2030 (CDC, 2024f).

The Hear Her Campaign

The Hear Her campaign is a national campaign in the United States that supports the efforts of the Division of Reproductive Health within the CDC. The Hear Her campaign seeks to educate individuals regarding peripartum mortality and important signs and symptoms to report to an HCP during both the prenatal and postpartum periods. The campaign also empowers individuals to bring their questions and concerns to their HCPs and attempts to improve communication between the patient and their HCPs. This campaign promotes the idea that individuals know their bodies better than anyone else, and HCPs should listen when they report a change or a feeling that something is wrong. The Hear Her campaign also distributes educational materials and tools to HCPs to help facilitate open communication and effective patient education. The Hear Her campaign is designed for patients, HCPs, and each patient’s support system, including their significant other, friends, and family (CDC, 2024c, 2024f).

The PMSS

The CDC completes the PMSS to gain knowledge related to the risk factors and causes of peripartum mortality in the United States. To gain knowledge about causes of mortality, researchers review birth and death records and any additional data relevant to peripartum mortality. Data from all 50 states is included, with additional information analyzed specifically for New York City and Washington, DC. The data gathered from the PMSS are also used to determine peripartum mortality rates, which are regularly posted on the CDC’s website and published in research on peripartum mortality (CDC, 2024f, 2025b).

PCQs

PQCs are state-specific or multistate teams with the goal of improving peripartum outcomes. The National Network of PQCs (NNPQC) was created by the CDC and the March of Dimes to support state-based PQCs to attain goals and improve peripartum outcomes. The PQCs aim to improve the quality of care delivered to patients by changing procedures and standards of care (CDC, 2024e). The following are some of the goals of PQCs:

- improve practices to screen for opioid use by pregnant individuals, access to SUD treatment, and improve the care of infants diagnosed with neonatal abstinence syndrome

- reduce the number of preterm births

- reduce the prevalence of severe hypertension, including the development of preeclampsia and eclampsia

- reduce disparities in accessibility and quality of care based on race and environment

- reduce the rate of delivery by cesarean section, particularly among individuals categorized as low-risk (CDC, 2024e)

PQCs have a history of improving patient outcomes regarding specific metrics. Examples include the Illinois PQC increasing the number of individuals who receive treatment for severe hypertension within 60 minutes from 41% to 79%, and the California PQC reducing the rate of hemorrhage during delivery or the postpartum period by 18% after 14 months of initiating care changes (CDC, 2024e).

CDC LOCATe

How states report peripartum mortality can vary, making it difficult to analyze trends in peripartum outcomes across states or geographical regions. The CDC developed the LOCATe to address this issue. This online tool aims to help standardize data reporting regarding peripartum outcomes. When utilized, the tool can provide data on the variances in patient outcomes, facility data, and the distribution of resources, including human resources. The purpose of the tool is to give an accurate representation of areas that need improvement to direct changes in health policy (CDC, 2024b).

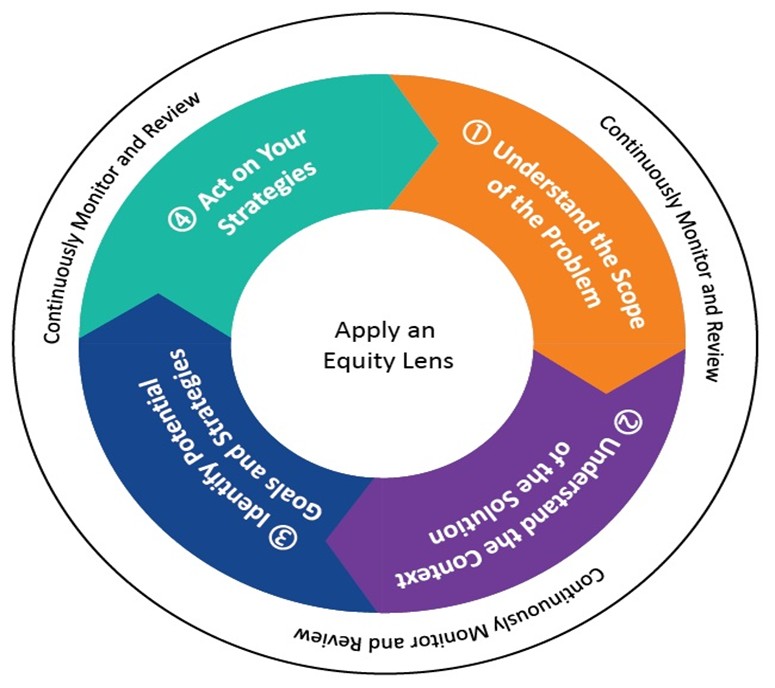

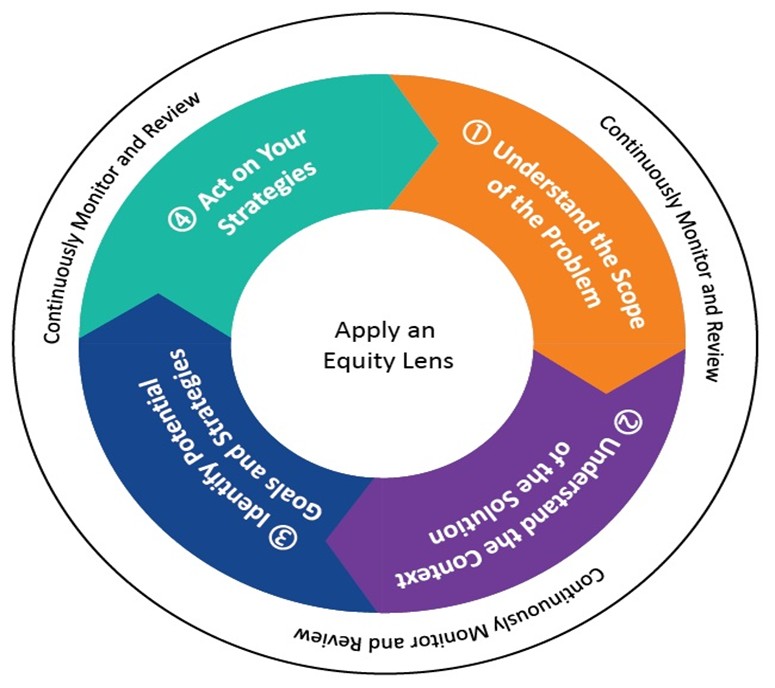

State Strategies for Preventing Pregnancy-Related Deaths

The State Strategies for Preventing Pregnancy-Related Deaths: A Guide for Moving Maternal Mortality Review Committee (MMRC) Data to Action is a resource available to help guide MMRCs and act as a resource during the implementation of new initiatives focused on improving peripartum health and decreasing mortality rates. The CDC supports 46 states and 6 US territories and freely associated states via the ERASE MM program. This resource is intended to be utilized once data are collected and decisions regarding addressing the identified problems have been discussed. It acts as a resource or tool for successfully implementing changes to maximize positive effects while limiting adverse outcomes resulting from the changes. This process is outlined in a 4-step process, each incorporating reviewing and monitoring of the implementation process (CDC, 2022, 2024d):

- Gather and use patient data to identify areas of deficiency requiring action.

- Determine if interventions have already been implemented and identify key stakeholders and available resources.

- Develop goals and strategies to address identified issues (e.g., eliminate racial and geographical disparities in the care of pregnant individuals and reduce peripartum mortality).

- Create a plan and timeline and implement the strategies outlined in step 3.

Figure 2 depicts how to use the State Strategies for Preventing Pregnancy-Related Deaths guide.

Figure 2

How to Use State Strategies for Preventing Pregnancy-Related Deaths

(CDC, 2022)

The Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality Strategy

The Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality Strategy is an initiative supported by the WHO that works to support countries that have high peripartum mortality rates. This initiative aims to:

- address inequalities in health care provided to pregnant individuals and their ability to access high-quality health care during the reproductive years, including prenatal and postpartum care

- ensure that all individuals have access to universal health care coverage for reproductive health needs and treatment

- focus on decreasing the prevalence of disorders or outcomes that can increase the risk of peripartum morbidity and mortality

- provide resources to facilitate health systems in collecting data that can track peripartum outcomes, thereby directing quality improvement initiatives

- implement practices that ensure health system and provider accountability to provide high-quality patient care (WHO, 2025)

Healthy People 2030

Improving peripartum and newborn outcomes and decreasing rates of morbidity and mortality have been addressed in the Healthy People initiative since the release of Healthy People 2000. This objective was also addressed in Healthy People 2020, but improvements toward goal achievement were not made. The goals related to peripartum health listed in Healthy People 2030 are to prevent the development of peripartum complications resulting from pregnancy, decrease the peripartum mortality rate, and improve the overall health of individuals during their reproductive years, including the prepregnancy, prenatal, and postpartum periods. Objectives linked to the goals that are specific to peripartum outcomes with associated progress from Healthy People 2020 (if applicable) are listed in Table 3 (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], n.d.).

Table 3

Healthy People 2030 Objectives and Progress

Category | Objective | Progress |

Pregnancy and Childbirth | increase the number of individuals who are screened for postpartum depression | in the developmental stage |

increase the number of pregnant individuals who receive timely and quality prenatal care | getting worse |

increase the number of individuals who have a healthy prepregnancy weight | getting worse |

Drug, Alcohol, and Tobacco Use | decrease the use of alcohol and illicit drugs (especially opioids) by pregnant individuals | little to no detectable change |

decrease the use of tobacco by pregnant individuals | target met or exceeded |

Family Planning | increase the length between pregnancies to 18 months | target met or exceeded |

reduce the number of unintended pregnancies | baseline only |

Women | reduce peripartum deaths | little or no detectable change |

reduce the number of cesarean sections performed on low-risk individuals with no birth history | Getting worse |

(ODPHP, n.d.)

Legislation

Legislatures have passed laws to decrease the peripartum mortality rate in this country (Douthard et al., 2021). Examples include the following (Douthard et al., 2021):

- The Preventing Maternal Deaths Reauthorization Act authorizes the CDC to support state and local MMRCs addressing peripartum mortality.

- The Improving Access to Maternity Care Act requires the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to identify areas that need peripartum health services and those lacking obstetric providers.

- The Affordable Care Act supports the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program, which provides home health care services to at-risk individuals and families.

- The 21st Century Cures Act promotes the sharing of health information between HCPs and systems to identify disparities in health care and widespread issues.

Roe v. Wade

The ACOG and other reproductive health organizations have voiced concerns that the Supreme Court’s vote to overturn Roe v. Wade in 2022 will have a negative impact on peripartum mortality rates in the United States. The overturning of Roe v. Wade gave the power to make decisions regarding abortion rights to the states. This means that the laws governing reproductive health can vastly vary based on geographical location. This change in law amplified the concerns of HCPs about their ability to care for their patients lawfully and provide them with the same level of care they were delivering under Roe v. Wade. The president of ACOG, Iffath Abbasi Hoskins, MD, released a statement following the Supreme Court’s decision on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization and the reversal of the precedent set, outlining how this decision will impact bodily autonomy, reproductive rights and health, patient safety and outcomes, and health care equity. Bans and restrictions imposed by individual states following this decision will create barriers to accessing appropriate medical care for many individuals. The states that have enacted restrictions on abortion have not based these restrictions on medical knowledge or scientific research and are effectively reducing the treatment options that can be offered to certain patients. These laws lead individuals to search for alternative ways to end unwanted pregnancies, increasing peripartum mortality rates (ACOG, 2022).

References

Ahmad, F. B., Cisewski, J. A., & Hoyert, D. L. (2025). Provisional maternal mortality rates. National Center for Health Statistics. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc/20250305011

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2018). ACOG committee opinion no. 736: Optimizing postpartum care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(5), e140–e150. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2022). ACOG statement on the decision in Dobbs V. Jackson. https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2022/06/acog-statement-on-the-decision-in-dobbs-v-jackson

Aziz, A., Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., Siddiq, J. D., Goffman, D., Sheen, J., D'Alton, M. E., & Friedman, A. M. (2019). Maternal outcomes by race during postpartum readmissions. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 220(5), 484.E1–484.E10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.016

Brown, H. L., & Small, M. J. (2025). Overview of maternal mortality. UpToDate. Retrieved September 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-maternal-mortality

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). State strategies for preventing pregnancy-related deaths: A guide for moving maternal mortality review committee data to action. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/119463/cdc_119463_DS1.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). About pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/pregnancy-related-deaths/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024b). CDC Levels of Care Assessment Tool (CDC LOCATe). https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/php/cdc-locate/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024c). Hear Her campaign: An overview. https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/about/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024d). Enhancing reviews and surveillance to eliminate maternal mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/erase-mm/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024e). Perinatal quality collaboratives. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/pqc

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024f). Preventing pregnancy-related deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/preventing-pregnancy-related-deaths/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024g). Severe maternal morbidity. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/php/severe-maternal-morbidity/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024h). Working together to reduce black maternal mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/womens-health/features/maternal-mortality.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025a). Births and natality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm#

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025b). Data from the pregnancy mortality surveillance system. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-data

Collier, A. Y., & Molina, R. L. (2019). Maternal mortality in the United States: Updates on trends, causes, and solutions. NeoReviews, 20(10), e561–e574. https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.20-10-e561

Douthard, R. A., Martin, I. K., Chapple-McGruder, T., Langer, A., & Chang, S. (2021). US maternal mortality within a global context: Historical trends, current state, and future directions. Journal of Women's Health, 30(2), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8863

Dulay, A. T. (2025). Maternal mortality and perinatal mortality. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gynecology-and-obstetrics/antenatal-complications/maternal-mortality-and-perinatal-mortality

Gunja, M. Z., Gumas, E. D., Masitha, R., & Zephyrin, L. C. (2024). Insights into the U.S. maternal mortality crisis: An international comparison. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/jun/insights-us-maternal-mortality-crisis-international-comparison

Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., Srinivas, S. K., Wright, J. D., Goffman, D., Siddiq, Z., D'Alton, M. E., & Friedman, A. M. (2018). Postpartum hemorrhage outcomes and race. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 219(2), 185.E1–185.E10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.04.052

Hoyert, D. L. (2024). Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2022. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2022/maternal-mortality-rates-2022.htm

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2025). Medicaid postpartum coverage extension tracker. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker

Lowdermik, D. L., Cashion, K., Alden, K. R., Olshansky, E., & Perry, S. E. (2023). Maternity & women's health care (13th ed.). Elsevier.

March of Dimes. (2024). Births. https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data

Melotte, S. (2022). Research: Rural maternal health is declining. https://dailyyonder.com/research-rural-maternal-health-is-declining/2022/08/15

Moroz, L. (2025). Severe maternal morbidity. UpToDate. Retrieved September 14, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/severe-maternal-morbidity

National Center for Health Statistics. (2024). NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-analysis-tools/urban-rural.html

National Center for Health Statistics. (2025). Births in the United States, 2024. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db535.htm#section_2

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2020a). What are examples and causes of maternal morbidity and mortality? https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/maternal-morbidity-mortality/conditioninfo/causes

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2020b). What factors increase the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality? https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/maternal-morbidity-mortality/conditioninfo/factors

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2021). Maternal morbidity and mortality. National Institute of Health. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/maternal-morbidity-mortality

Norris, K., & Harris, C. E. (2024). Use of race and ethnicity in medicine. UpToDate. Retrieved September 16, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/use-of-race-and-ethnicity-in-medicine

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Pregnancy and childbirth. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved September 18, 2025, from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/pregnancy-and-childbirth

Okunlola, O., Raza, S., Osasan, S., Sethia, S., Batool, T., Bambhroliya, Z., Sandrugu, J., Lowe, M., & Hamid, P. (2022). Race/ethnicity as a risk factor in the development of postpartum hemorrhage: A thorough systematic review of disparity in the relationship between pregnancy and the rate of postpartum hemorrhage. Cureus, 14(6), e26460. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.26460

Osterman, M. J. K., Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., Driscoll, A. K., & Valenzuela, C. P. (2025). Births: Final data for 2023. National Vital Statistics Reports, 74(1). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr74/nvsr74-1.pdf

Ricks, T. N., Abbyad, C., & Polinard, E. (2021). Undoing racism and mitigating bias among healthcare professionals: Lessons learned during a systematic review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9, 1990–2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01137-x

Shah, H. S., & Bohlen, J. (2023). Implicit bias. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589697

SisterSong. (n.d.). Reproductive justice. Retrieved September 16, 2025, from https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice

Thoma, M. E., & Declercq, E. R. (2022). All-cause maternal mortality in the US before vs. during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 5(6), e2219133. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19133

United Nations Children's Fund. (2025). Maternal mortality. https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality

Wallace, M. E. (2022). Trends in pregnancy-associated homicide, United States, 2020. American Journal of Public Health, 112(9), 1333–1336. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306937

Wallace, M. E., & Jahn, J. L. (2025). Pregnancy-associated mortality due to homicide, suicide, and drug overdose. JAMA Network Open, 8(2), e2459342. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.59342

World Health Organization. (2025). Maternal mortality. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

Powered by Froala Editor