This course provides an overview of urinary incontinence in females, including risk factors, assessment, evaluation, and pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment strategies.

...purchase below to continue the course

outlet obstruction. This type of UI can be harmful because incomplete bladder emptying can lead to renal failure and permanent bladder damage. OUI is less common, accounting for 5% of all UI cases (Leslie et al., 2024; Shenot, 2025).

Anatomy and Physiology

The process of storing and releasing urine, or micturition, involves sympathetic, parasympathetic, and somatic innervation. The detrusor muscle, a smooth muscle surrounding the bladder, typically stays relaxed when the bladder is filled from the ureters. As the bladder expands, the detrusor muscle sends a signal to the spinal cord and the brain through the cortical micturition center. This signal stimulates an increase in the parasympathetic response and a decrease in the sympathetic response. The change in the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems triggers the bladder to contract and the sphincter to relax. Signals are sent from the spinal cord to the parietal lobe and thalamus, which in turn control the detrusor muscle. The pontine center of the brain coordinates the signals that allow micturition to occur when socially appropriate. While the signals to the spinal cord stimulate the body to release urine, the pons in the brain is responsible for delaying urination until the individual is near a toilet. Sphincters at the bladder neck between the bladder and the urethra function as “gatekeepers” to keep urine from flowing out of the bladder (Barrett et al., 2019; Conner et al., 2019; Flores et al., 2023).

Risk Factors

Risk factors for all categories of UI include a BMI above 30 kg/m2, a history of vaginal births, urethral trauma, POP, and postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Approximately 44% of females with UI have POP. Certain medications, including diuretics, hypnotics, and sedatives, can trigger UI symptoms. Additionally, antispasmodic agents can lead to SUI symptoms. While SUI and UUI are the two main symptom patterns, there are also other causes of UI. For instance, a neurogenic bladder caused by conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injury may also lead to UI. However, these are considered complicated UI and are beyond the scope of this course (Conner et al., 2019; Leslie et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025a; Wong & Ramm, 2021).

Evaluation and Diagnosis

The workup for symptoms of UI should begin with a thorough history (refer to Table 1), physical examination, and urinalysis. A comprehensive assessment helps to identify underlying or contributing causes; differentiate between the types of UI; and guide the appropriate treatment strategies. Since many patients are embarrassed to mention incontinence, healthcare providers (HCPs) should question all adult patients about involuntary urine leaks. The acronym DIAPPERS (delirium, infection, atrophic urethritis/vaginitis, pharmaceutical, psychological morbidity, excess fluid intake, restricted mobility, and stool impaction) serves as a guide for collecting a detailed history of UI to rule out underlying causes. Attention should be paid to any prior conditions affecting the pelvic, urinary, and renal systems, such as previous surgeries and kidney stones. A history of any of these underlying conditions suggests complicated UI and warrants referral to a specialist for further evaluation. The presence of diminished self-care ability, mobility restrictions, or communication problems (aphasia or other language impairment) suggests functional causes of incontinence, which should be treated by providing appropriate assistance or devices that address the underlying difficulties. HCPs should ask about fever, dysuria, pelvic pain, and hematuria to rule out a urinary tract infection (UTI). The 3 incontinence questionnaire (3IQ) is a validated instrument that HCPs can administer to identify symptoms of UI and determine the type (Conner et al., 2019; Lukacz, 2025a; Nandy & Ranganathan, 2022; Shenot, 2025).

In addition to a thorough medical history, a thorough obstetric and gynecological history should be collected as well. A history of multiple vaginal deliveries increases a patient’s risk of pelvic floor weakness, POP, and perineal trauma. The HCP should assess for conditions associated with estrogen deficit, such as menopause. Multiple validated questionnaires are available to assist the HCP when taking a focused history for UI. Examples include the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ), and the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI). These evaluate for potential symptoms of bladder dysfunction, POP, and bowel dysfunction. The short form of the PFDI also assesses the severity of symptoms, while the PGIQ focuses on lifestyle and the daily impact of the reported symptoms (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, n.d.; Grimes & Stratton, 2023; Nandy & Ranganathan, 2022).

A complete voiding history provides valuable information and should include the following: onset of incontinence, the number of voids in a day, the amount of urine leaked, a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, and the presence of dysuria. The patient should also be screened for nocturia and polyuria, which may reflect underlying conditions such as heart failure or diabetes. A fluid intake history should include the types and amounts of fluid the patient consumes to evaluate for excessive fluid intake (more than 64 ounces per day), caffeine intake, and other potential bladder irritants (e.g., alcohol, carbonated beverages, and tobacco products). This information is typically collected via a voiding diary, which provides details regarding fluid intake, voids, and activity around the time of any leakage for at least three days. If the presence of UI is questionable, a pad test is recommended. The patient is given phenazopyridine hydrochloride HCL (Pyridium) to stain their urine while wearing a sanitary pad or absorbent product. The patient checks the pad periodically for staining from urine loss (Conner et al., 2019; Lukacz, 2025a; Nandy & Ranganathan, 2022; Shenot, 2025).

Table 1

Essential Considerations in the History of Patients with UI

Voiding History | Medical Conditions |

Voiding pattern Onset of the problem Duration of the problem Are the symptoms bothersome? | Diabetes mellitus Diabetes insipidus Urological/gynecological cancer Chronic cough Altered mental status BMI above 30 kg/m2 Previous pelvic surgeries Chronic constipation |

Fluid Intake | Medications |

Caffeine intake Carbonated drinks Artificial sweeteners Alcohol use Excessive fluid intake | Alpha-adrenergic agonists or antagonists Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors Antiarrhythmics Estrogens Muscle relaxants Antihistamines Decongestants Anticholinergics Calcium channel blockers Sedatives or hypnotics Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) Lithium (Lithobid) Psychotropic medications Opioids Diuretics |

Triggering Factors | |

Sneezing or coughing Lifting Running water Bending Sexual intercourse Sudden change in movement or position |

|

(Conner et al., 2019; Hu & Pierre, 2019; Leron et al., 2018)

Physical Examination

Information obtained from the health history should guide the focused physical exam. A previously healthy female with no underlying abdominal or neurological conditions may only need an abdominal and pelvic exam. The abdomen should be assessed for signs of constipation, masses, a distended bladder, or cystitis. A pelvic examination should be performed to evaluate the strength of the pelvic floor musculature, POP, and atrophy of the vaginal mucosa. The patient should be placed in the lithotomy position to inspect the perineum. POP can sometimes be visualized by the protrusion of the vaginal walls or uterus at the introitus. After inspection, pelvic floor strength can be assessed manually by placing one finger into the vaginal vault and asking the patient to squeeze the inserted finger to test the tone of the pelvic floor. Atrophic changes of the vaginal epithelium will typically cause the mucosa to appear smoother in texture and paler in color than previously. A rectal examination may be indicated to assess for the presence of stool in the rectal vault. Constipation can be a contributing factor to UI. A cardiovascular exam to evaluate for volume overload is essential for patients with underlying cardiovascular disease and risk factors (Conner et al., 2019; Vaughan & Markland, 2020). Depending on the health history, a more detailed physical examination may be indicated to identify potential causes (refer to Table 2).

Table 2

Physical Examination Considerations by Body System

Body System | Physical Examination |

General | Vital signs, BMI |

Cardiovascular and pulmonary | Pulmonary crackles, cough, pedal edema, jugular venous distention |

Abdominal | Scars, masses, hernias, bladder distension, bladder tenderness, panniculus, suprapubic muscle tone, costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness |

Gynecological | Pelvic floor strength, prolapsed uterus, vaginal mucosa, vaginitis, cystocele, rectocele |

Urological | Urethral sphincter strength |

Rectal | Sphincter tone, fecal impaction |

Neurological | Gait, cognitive function, sensation, reflexes |

Dermatological | Skin breakdown |

(Nandy & Ranganathan, 2022)

Additional Testing

Additional exam techniques may be incorporated to confirm findings. A bladder or cough stress test can confirm suspected SUI or MUI if there is evidence of urine loss when the patient is directed to cough while the examiner inspects the urethral meatus. This test can be performed standing or supine; however, the supine or lithotomy position is the most convenient to visualize the urethra. The bladder must be at least partially full for the test to be valid. The bladder stress test has a positive predictive value of 78–97%. The cotton swab test, typically completed by urology, assesses for urethral hypermobility in a patient with SUI. The urethra is lubricated, and a swab is inserted into the neck of the bladder. If the angle of the swab changes more than 30 degrees during a Valsalva maneuver, the test is considered positive. There may be poor agreement of the test result when the angle is between 21 and 49 degrees (Guralnick et al., 2018; Harris et al., 2025; Lukacz, 2025a; Nandy & Ranganathan, 2022).

Most patients with UI will only need a physical exam and a simple urinalysis for evaluation. The urine should be sent for culture and sensitivity if the urinalysis suggests a possible infection. HCPs should also consider screening patients for diabetes since polyuria can be confused with frequency and urgency. Additional laboratory testing can be done based on the history and physical examination findings. Evaluation of kidney function should be included if there is a concern for severe urinary retention resulting in hydronephrosis. A postvoid residual bladder sonogram should be considered if a patient does not respond to first-line interventions or reports obstructive symptoms such as a weak urine stream or urinary hesitancy. Patients at risk of OUI are those with neurological disease, recurrent UTIs, a history of detrusor underactivity or urinary retention, severe constipation, POP, diabetes with peripheral neuropathy, or medications that suppress detrusor contractility or increase sphincter tone. Generally, a PVR of less than one-third of the total voided volume is considered adequate emptying. Other tests that a urological specialist may complete include uroflowmetry and a voiding cystourethrogram, but these are not indicated for initial workups and uncomplicated cases (Cameron et al., 2024; Harding et al., 2025; Lukacz, 2025a; Nandy & Ranganathan, 2022).

Treatment/Management

Once diagnosed and correctly characterized, the first step in managing UI is establishing treatment priorities based on the patient’s care goals and managing expectations. The goals typically include improving quality of life by focusing on the patient’s most bothersome symptoms, but rarely is full continence achieved. Treatment should proceed in a stepwise fashion, starting with the least invasive options. Tools to assist the assessment of symptom impact may help focus treatment goals and track efficacy, such as the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire, the King’s Health Questionnaire, PFDI, PFIQ, the OAB Questionnaire, and the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGII) or Severity (PGIS; Balk et al., 2019; Leslie et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025b; Shenot, 2025).

Nonpharmacological Treatments

Treatment of UI should then proceed with nonpharmacological measures and a multidisciplinary approach to managing symptoms. Any aggravating factors that contribute to the symptoms should be removed or controlled. If the medication review reveals drugs that may exacerbate symptoms, the HCP should consider changing the schedule or dosage to check if symptoms decrease. Conditions such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and postnasal drainage should be fully optimized to ameliorate a chronic cough from contributing to SUI. Additional lifestyle modifications that may benefit those with UI include smoking cessation; avoidance of alcoholic, caffeinated, and carbonated beverages; and maintaining a fluid intake of 64 ounces per day or less. Patients with nocturia symptoms should avoid fluid intake within several hours (3–4) of their bedtime. Patients with cognitive impairment or restricted mobility can benefit from a portable commode, absorbent pads, or padded undergarments (Leslie et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025b; Shenot, 2025; Winkelman & Elkadry, 2021).

One of the main risk factors for UI is a BMI of greater than 30 kg/m2, particularly when this occurs after the onset of menopause and when the weight is concentrated in the abdomen. Weight loss is more effective at reducing symptoms of SUI, but all UI symptoms may improve. Weight loss has been found to improve UI symptoms as much as surgical interventions. One randomized controlled trial comparing a 6-month intensive weight loss program to usual care found a 70% reduction in SUI episodes in the intervention group. The European Association of Urology’s (EAU) 2025 guidelines include strong evidence for recommending weight loss to patients with UI if their a BMI is greater than 30 kg/m2. The patient should be counseled about the efficacy of weight loss for improving their symptoms of UI as well as the overall benefit to general health (Harding et al., 2025; Leslie et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025b).

UI treatment should consist of pelvic floor muscle therapy (PFMT) to strengthen and improve the tone and endurance of the musculature to support the pelvic organs. A recent Cochrane review supported PFMT as a first-line therapy for SUI, UUI, and MUI, a recommendation reinforced by the World Health Organization (WHO). PFMT is a safe and effective intervention with high satisfaction rates from patients. PMFT is more effective at reducing symptoms of SUI but is at least partially effective for all UI symptoms. Kegel maneuvers are the most widely known pelvic floor exercises. The first step in teaching a patient to perform a Kegel maneuver is to help them identify the correct muscles to contract. One way to introduce the maneuver is to have the patient squeeze an examining finger placed in the vaginal introitus during a pelvic exam. Patients can also be instructed to imagine they are trying to hold in urine or flatulence. Ensure that the patient feels a sensation of lift in the pelvic floor with the contraction. It is critical to explain that they must not contract during urination as this can weaken the pelvic floor muscles if done continuously or repeatedly (Cho & Kim, 2021; Dumoulin et al., 2018; Lugo et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025b; Shenot, 2025; Todhunter-Brown et al., 2022; WHO, 2017).

Once the patient identifies the correct muscles to contract, they should perform five contractions, holding each contraction for 1–2 seconds and gradually lengthening to 8–10 seconds. Patients should initially practice the exercises in the prone position and progress to sitting and then to standing as they feel more confident in their pelvic strength. This series should be completed three times daily for 15–20 weeks to achieve a benefit. Some patients may have difficulty performing Kegel exercises correctly and effectively. A referral to a physical therapist specializing in pelvic floor disorders may be needed to improve the efficacy of PFMT. EAU guidelines recommend intensive PFMT with a trained physical therapist for at least 3 months. Physical therapists trained in PFMT provide a wide range of therapies to improve symptoms, including coordination exercises to enhance bladder control and release; stretching and strengthening the legs, trunk, and pelvic muscles; biofeedback; heat and ice; electrical stimulation; and relaxation exercises. Mobile device applications (apps) for UI self-management hold promise as an option for patients to reinforce PFMT exercises. A systematic review of mobile health applications (e.g., Tät®, UrinControl) reported improved SUI symptoms and quality of life scores. More than 100 apps can be found for different mobile device platforms and often have built-in reminder systems to improve adherence (Cho & Kim, 2021; Harding et al., 2025; Hou et al., 2022; Lugo et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025b; National Association for Continence, n.d.).

In addition, bladder training may be a helpful tool in managing UUI and MUI conservatively. The patient’s shortest voiding interval (based on their voiding diary) should be used as a starting point for timed voiding throughout the waking hours. If urgency occurs within this interval, the patient should be encouraged to utilize mental relaxation techniques (i.e., mindful breathing) as well as distraction. To manage bladder contractions, the patient should also be trained in rapid contractions of the pelvic floor muscles (i.e., quick flicks). Once the patient can successfully avoid any leaks for an entire day using this initial interval period, the interval period should be extended the following day by 15 minutes. This interval is continuously lengthened until the patient can void every 3–4 hours without incontinence episodes or urgency (Harding et al., 2025; Lugo et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025b; Shenot, 2025).

Several commercially available products are designed for urine containment. Patients may try products designed for menstrual blood flow, but these are not ideal for urine. Menstrual pads are designed to hold a smaller amount of fluid (approximately 10 mL), whereas incontinence pads and disposable underwear are designed to contain up to 1000 mL of urine. Regardless of the cause or type, most patients with UI utilize disposable undergarments or pads. In the United States, these products are easily accessible but may be expensive over time; insurance plans rarely cover the cost, and these do not address the underlying cause of UI. These products can also lead to contact dermatitis or skin breakdown if they are not changed frequently enough. These patients should undergo urodynamic testing to assess bladder storage pressures and avoid consequent renal damage. Indwelling or intermittent bladder catheterization is associated with a high risk of infection. As a result, it is reserved for limited instances in which there are few alternatives. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that behavioral treatments, alone or in conjunction with other interventions, are more effective than pharmacological interventions alone (Balk et al., 2019; Lukacz, 2025b).

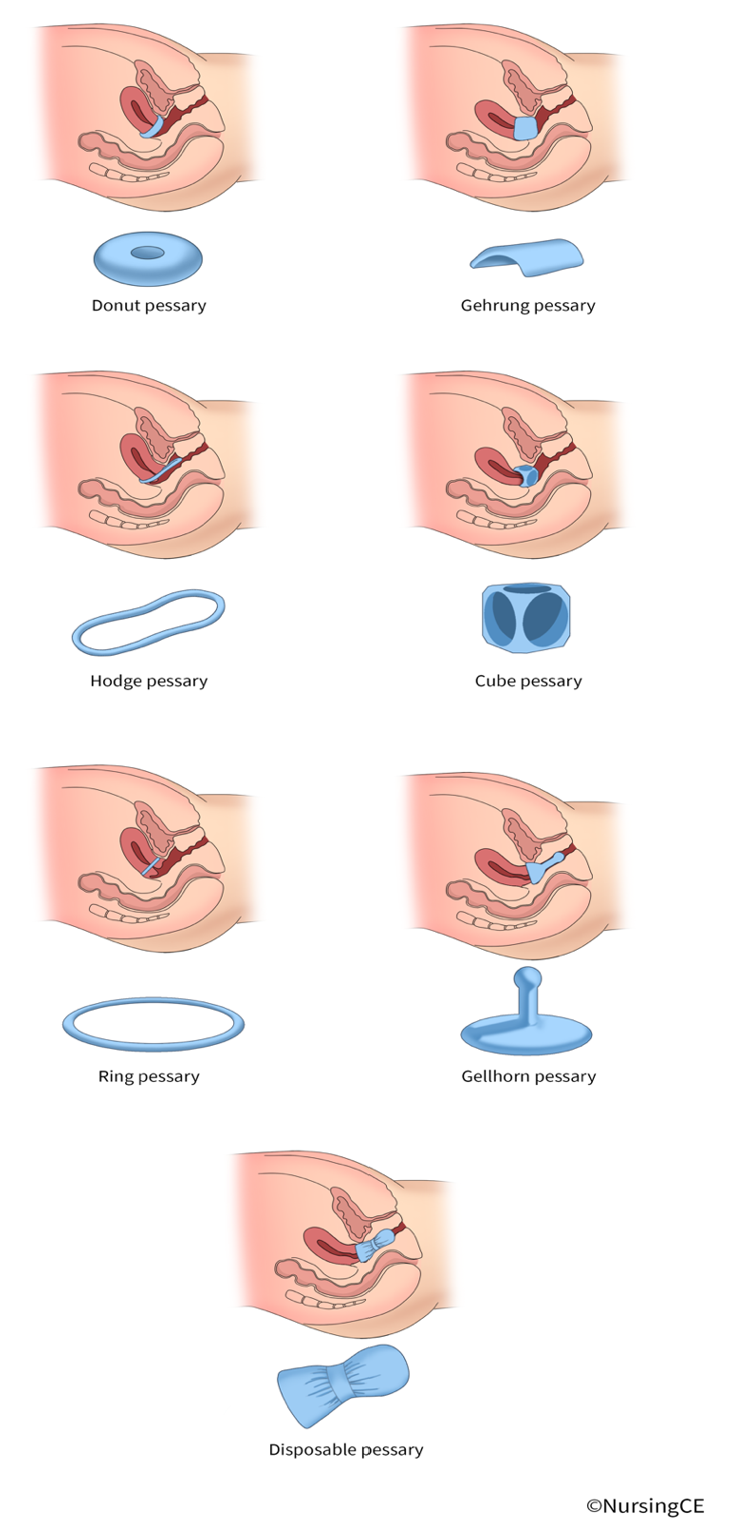

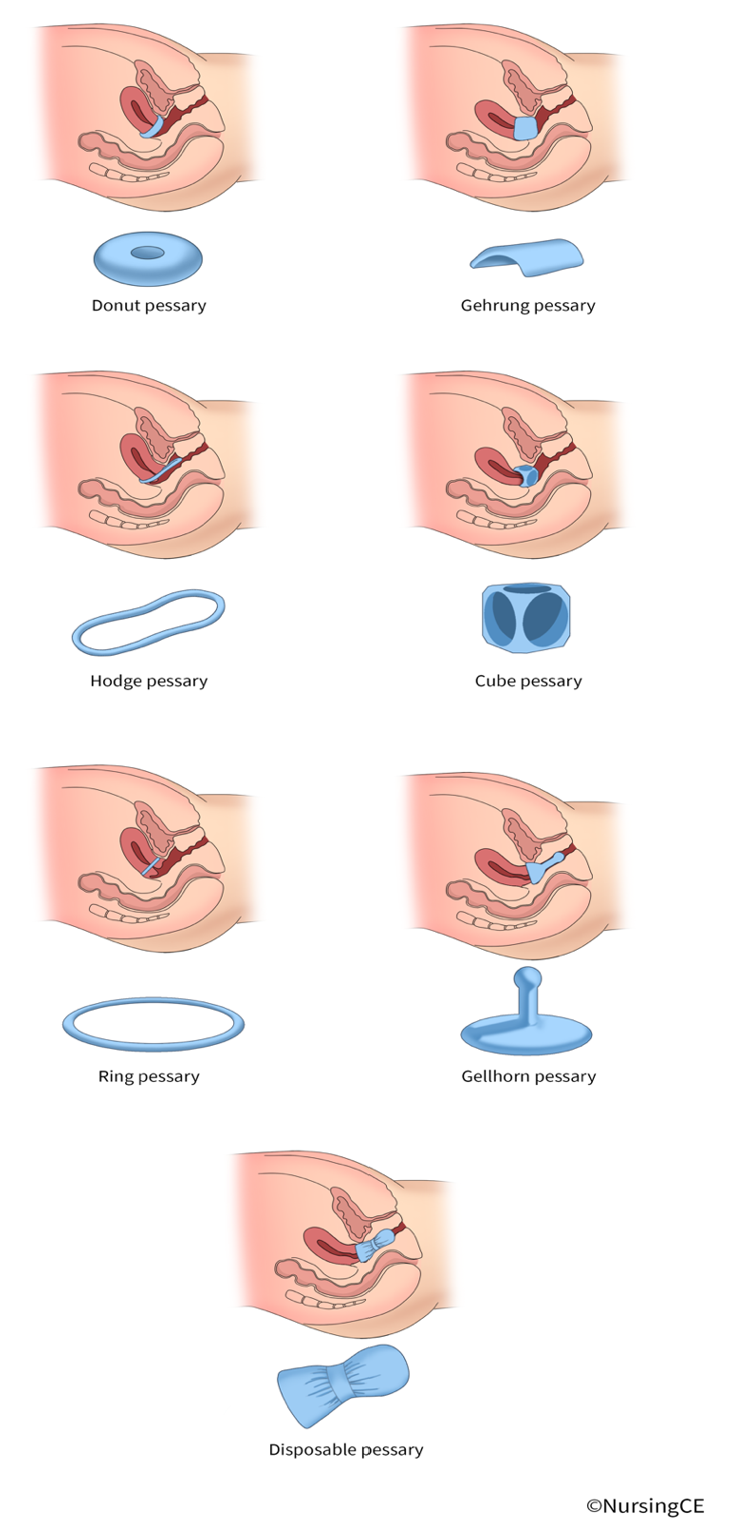

Pessaries are devices inserted into the vagina to support prolapsed pelvic organs (refer Figure 1). Although forms of pessaries have been used for centuries, modern devices are made of silicone and prescribed and fitted by trained HCPs, usually in gynecology or urogynecology practices. Pessaries come in various shapes and sizes depending on specific factors such as uterine shape, the size of the vaginal introitus, and the need for urethral support. They are often recommended for SUI and POP before surgical interventions and for patients who wish to avoid surgery. After an initial fitting, a follow-up appointment in 1–2 weeks provides an opportunity to assess for comfort, fit, and symptom improvement. Only an annual follow-up is needed for patients who can independently remove and insert the device. Pessaries and PMFT have similar long-term results regarding patient satisfaction and symptom control (Clemons, 2025; Lukacz, 2025b; Vaughan & Markland, 2020; Winkelman & Elkadry, 2021).

Figure 1

Continence Pessaries

A newer product, Poise Impressa™, was designed for SUI. It is a disposable over-the-counter vaginal support (i.e., pessary-like) device to be worn intravaginally. The device looks similar to a tampon and is inserted using a similar applicator but has an internal structure that supports the urethra to prevent leakage during activity. A fitting kit is available for patients to determine which size (S/M/L) provides the best control. This is a potential solution for females with intermittent symptoms of SUI during specific activities (e.g., exercise; Poise®, n.d., Winkelman & Elkadry, 2021).

Pharmacological Management

Pharmacological management is another option for patients with UI. A trial of an antimuscarinic agent or a beta-3 adrenergic agonist may be considered for patients with UUI who do not respond to conservative measures. Several agents with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for OAB may help with symptoms of UUI. Traditionally, antimuscarinic agents have been common treatments for OAB but are falling out of favor due to recent evidence of cognitive side effects and risk of dementia. Use of the medication’s extended-release (ER) formulation may mitigate these effects. These medications block acetylcholine from stimulating the muscarinic receptors, thus reducing smooth muscle contraction within the bladder, decreasing urgency, and increasing bladder capacity. These are typically available in a generic version that is lower in cost for most patients. Anticholinergic side effects that can be anticipated include dry mouth, dizziness, constipation, tachycardia/palpitations, and dry eyes (Lukacz, 2025c; Nandy & Ranganathan, 2022; Shenot, 2025; Welk & McArthur, 2020). Dosing considerations include (Lukacz, 2025c):

- Darifenacin (Enablex) ER can be dosed at 7.5 mg initially with a maximum of 15 mg daily.

- Fesoterodine (Toviaz) ER can be dosed at 4 mg initially, with a maximum of 8 mg daily.

- Oxybutynin (Ditropan) can be dosed at 5 mg orally two or three times daily if using the immediate release (IR) version, with a maximum daily dose of 5 mg four times daily; for the ER formulation, the starting dose is 5–10 mg once daily with a maximum daily dose of 30 mg. It is available as a 10% transdermal gel packet/satchel or pump with a prescription and in a 3.9 mg transdermal patch that should be applied to the hip, abdomen, or buttock and rotated every 3–4 days. The transdermal patch is available OTC in the United States. It is considered an alternative agent for OAB.

- Solifenacin (Vesicare) should be started at 5 mg once daily with a maximum of 10 mg daily.

- Tolterodine (Detrol) ER should be started at 2 mg daily and increased to 4 mg daily if needed. The IR version begins at 1 mg twice daily and can be increased to 2 mg twice daily. It is considered an alternative agent for OAB.

- Trospium (Sanctura) ER is dosed at 60 mg daily and should not be increased, while the IR version can be started at 20 mg daily and increased to twice a day dosing. It should be taken on an empty stomach.

Darifenacin (Enablex), solifenacin (Vesicare), fesoterodine (Toviaz), and tolterodine (Detrol) dosing may need to be decreased for renal/hepatic impairment. These medications are contraindicated in patients with untreated narrow-angle glaucoma, supraventricular tachycardia, and gastric retention. The increased risk of cognitive decline (i.e., dementia, Alzheimer’s disease) should be discussed with the patient to establish shared decision-making. They should not be combined with other anticholinergics (e.g., antihistamines, muscle relaxants, tricyclic antidepressants, and bronchodilators; Lukacz, 2025c).

Mirabegron (Myrbetriq) and vibegron (Gemtesa) are beta-3 adrenergic agonists approved for the treatment of OAB symptoms; they cause smooth muscle relaxation in the bladder by stimulating the beta-3 adrenergic receptors. They appear to be as effective as antimuscarinic agents with a lower incidence of anticholinergic side effects. Typical side effects include headache, rhinorrhea, or gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (e.g., nausea, diarrhea, constipation). They may also cause urinary retention. Mirabegron (Myrbetriq) may also elevate blood pressure. Mirabegron (Myrbetriq) ER should be started at 25 mg daily and increased to 50 mg daily in those with healthy renal and liver function if the response is inadequate. Mirabegron (Myrbetriq) can also be combined with solifenacin (Vesicare) in those with refractory/recurrent symptoms of OAB. Vibegron (Gemtesa) should be started at 75 mg daily, with the added advantage of being able to crush the pills for ease of administration if needed (Leron et al., 2018; Lukacz, 2025c; Shenot, 2025).

There are no FDA-approved medications for SUI; however, some are used off-label as second-line treatments. Duloxetine (Cymbalta), a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), can be offered to females with SUI or MUI to decrease incontinence episodes; side effects such as fatigue, insomnia, dizziness, dry mouth, and GI symptoms limit tolerability. Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is generally avoided in patients with chronic liver disease. Its use may be most appropriate for patients with concomitant depression or chronic pain (Anand et al., 2020; Harding et al., 2025; Lukacz, 2025b). A standard dose of topical estrogen may improve UI symptoms in post-menopausal females with vaginal atrophy or genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). These are available as creams (0.5 gm), gel caps, or tablets (10 mcg), typically dosed twice weekly; the vaginal ring is dosed every 3 months. Patients should be warned that they may not notice results for up to 3 months. It appears to be less effective than PFMT in trials for SUI symptom improvement. Studies indicate minimal systemic absorption with no significant increase in cardiovascular or cancer risk. Systemic hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may worsen incontinence and is not recommended (Harding et al., 2025; Lugo et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025b; Shenot, 2025).

Other Interventions

Other management options for SUI include injections and surgery. Periurethral bulking agents (UBAs) are injected cystoscopically. The American Urological Association/Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (AUA/SUFU) 2023 guidelines include UBAs as an option for SUI, but long-term data are lacking. For this reason, UBAs are rarely used other than in scenarios where the patient is unwilling or unable to tolerate an invasive procedure or in cases of refractory incontinence. Options are either particulate or nonparticulate, and brands currently include Durasphere EXP, Macroplastique, Coaptite, and Bulkamid (Morgan, 2022). The EAU guidelines suggest that electromagnetic stimulation is not effective for SUI symptoms but that electroacupuncture may be beneficial for some patients (Harding et al., 2025).

Surgical options are designed to support the bladder and urethra using synthetic mesh or autologous slings. The AUA/SUFU 2023 guidelines recommend that all patients considering surgery be thoroughly counseled about the benefits, risks, and potential outcomes. POP can mask SUI symptoms, so it is important to counsel patients that they may notice more SUI after POP repair. A suburethral sling is surgically inserted through the vagina and then placed at the bladder neck, midurethra, or proximally to support the urethra. A pubovaginal sling includes a blabber neck and proximal support placed through an abdominal and vaginal incision. A midurethral sling can be placed during an outpatient procedure with a low risk of complications. They are often performed in a tension-free manner via a vaginal approach. Abdominal approaches may also be used to perform laparoscopic procedures such as the Burch or Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz (MMK). These use sutures to suspend the vaginal wall adjacent to the midurethra and bladder neck in a retropubic position. These may be referred to as retropubic colposuspension or urethropexy. A direct comparison (randomized trial) between surgical and conservative therapy (including physiotherapy) found that 90% of surgical candidates felt their symptoms had improved, versus 64% of conservative candidates. The valid concerns with surgical intervention include an increased risk of morbidity, postoperative voiding complications, and worsened (or new) UUI. Other trials have indicated efficacy rates of 40% for pelvic floor therapy, biofeedback, and pessaries versus 70–80% for surgical interventions (Jelovsek & Reddy, 2024; Kobashi et al., 2023; Vaughan & Markland, 2020).

If pharmacological interventions fail to improve symptoms of UUI, other options include neuromodulation and onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox). Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation involves a series of in-office treatments over several months. An implantable sacral neuromodulator device sends electrical signals to the sacral nerve plexus. OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) may be injected into the bladder cystoscopically to temporarily paralyze the muscles responsible for causing voiding urgency. Unfortunately, surgical procedures for UUI are limited, and evidence of benefit is weak (Kobashi et al., 2023; Lukacz, 2025c; Vaughan & Markland, 2020).

Conclusion

UI is a common condition, and HCPs should have a working knowledge of the signs, symptoms, and treatment options. Since patients may not bring up the subject, it is essential to inquire about symptoms of UI with all female patients. A thorough history and physical exam are the first steps in identifying appropriate treatment options. Conservative measures should include pelvic floor exercises, fluid management, bladder training, and weight management. They are safe and effective and form the foundation of treatment for females with all types of UI. When needed, patients should be referred to a physical therapist specializing in pelvic floor therapy to maximize the benefit of exercise. Pharmacological options are available, but side effects limit their use; most drugs are only approved for UUI and OAB symptoms. Patients who do not improve with conservative measures and first-line medications should be referred to urology specialists for consideration of additional treatment options (Leslie et al., 2024; Lukacz, 2025a, 2025b; Shenot, 2025).

References

Anand, A., Khan, S. M., & Khan, A. A. (2020). Stress urinary incontinence in females. Diagnosis and treatment modalities—Past, present, and the future. Journal of Clinical Urology, 16(6), 622–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/20514158211044583

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Urinary incontinence. Retrieved November 1, 2025, from https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/urinary-incontinence

Balk, E. M., Rofeberg, V. N., Adam, G. P., Kimmel, H. J., Trikalinos, T. A., & Jeppson, P. C. (2019). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for urinary incontinence in women: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170(7), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-3227

Barrett, K. E., Brooks, H. L., Barman, S. M., & Yuan, J. (2019). Renal function & micturition. In Ganong's Review of Medical Physiology (26th ed). McGraw-Hill Education.

Cameron, A. P., Chung, D. E., Dielubanza, E. J., Enemchukwu, E., Ginsberg, D. A., Helfand, B. T., Linder, B. J., Reynolds, W. S., Rovner, E. S., Souter, L., Suskind, A. M., Takacs, E., Welk, B., & Smith, A. L. (2024). The AUA/SUFU guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic overactive bladder. The Journal of Urology, 212(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000003985

Cho, S. T., & Kim, K. H. (2021). Pelvic floor muscle exercise and training for coping with urinary incontinence. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 17(6), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.2142666.333

Clemons, J. L. (2025). Vaginal pessaries: Indications, devices, and approach to selection. UpToDate. Retrieved November 1, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vaginal-pessaries-indications-devices-and-approach-to-selection

Conner, D. N., Thomas, D. J., & Porter, B. O. (2019). Urinary tract disorders. In J. E. Winland-Brown, L. M. Dunphy, L. M., B. O. Porter, & D. J. Thomas (Eds.), Primary care: The art and science of Advanced Practice Nursing—An interprofessional approach (5th ed., pp. 628–649). F. A. Davis Company.

Dumoulin, C., Cacciari, L. P., & Hay-Smith, E. J. (2018). Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (10). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub4

Duralde, E. R., & Rowen, T. S. (2017). Urinary incontinence and associated female sexual dysfunction. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 5(4), 470–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.07.001

Flores, J. L., Cortes, G. A., & Leslie, S. W. (2023). Physiology, urination. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562181

Grimes, W. R., & Stratton, M. (2023). Pelvic floor dysfunction. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559246

Guralnick, M. L., Fritel, X., Tarcan, T., Espuna-Pons, M., & Rosier, P. F. W. M. (2018). ICS educational module: Cough stress test in the evaluation of female urinary incontinence: Introducing the ICS-uniform cough stress test. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 37, 1849–1855. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23519

Harding, C. K., Lapitan, M. C., Arlandis, S., Bø, K., Cobussen-Boekhorst, H., Costantini, E., Groen, J., Nambiar, A. K., Omar, M. I., Peyronnet, B., & Phé, V. (2025). EAU Guidelines on non-neurogenic female lower urinary tract symptoms. EAU Guidelines Office. https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-neurogenic-Female-LUTS-2025.pdf

Harris, S., Leslie, S. W., & Riggs, J. (2024). Mixed urinary incontinence. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534234

Hou, Y., Feng, S., Tong, B., Lu, S., & Jin, Y. (2022). Effect of pelvic floor muscle training using mobile health applications for stress urinary incontinence in women: A systematic review. BMC Women’s Health, 22(400), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01985-7

Hu, J. S., & Pierre, E. F. (2019). Urinary incontinence in women: Evaluation and management. American Family Physician, 100(6), 339–348. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/0915/p339.html

Jelovsek, J. E., & Reddy, J. (2024). Female stress urinary incontinence: Choosing a primary surgical procedure. UpToDate. Retrieved November 1, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/female-stress-urinary-incontinence-choosing-a-primary-surgical-procedure

Kobashi, K. C., Vasavada, S., Bloschichak, A., Hermanson, L., Kaczmarek, J., Kim, S. K., & Malik, R. (2023). Updates to surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence (SUI): AUA/SUFU guideline (2023). The Journal of Urology, 209(6), 1091–1098. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000003435

Leron, E., Weintraub, A. Y., Mastrolia, S. A., & Schwarzman, P. (2018). Overactive bladder syndrome: Evaluation and management. Current Urology, 11(1), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447205

Leslie, S. W., Tran, L. N., & Puckett, Y. (2024). Urinary incontinence. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559095

Lugo, T., Leslie, S. W., Mikes, B. A., & Riggs, J. (2024). Stress urinary incontinence. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539769

Lukacz, E. S. (2025a). Female urinary incontinence: Evaluation. UpToDate. Retrieved October 30, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/female-urinary-incontinence-evaluation

Lukacz, E. S. (2025b). Female urinary incontinence: Treatment. UpToDate. Retrieved November 1, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-urinary-incontinence-in-females

Lukacz, E. S. (2025c). Urgency urinary incontinence/overactive bladder (OAB) in females: Treatment. UpToDate. Retrieved November 1, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/urgency-urinary-incontinence-overactive-bladder-oab-in-females-treatment

Morgan, D. M. (2022). Stress urinary incontinence in females: Persistent/recurrent symptoms after surgical treatment. UpToDate. Retrieved November 1, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/stress-urinary-incontinence-in-females-persistent-recurrent-symptoms-after-surgical-treatment

Nandy, S., & Ranganathan, S. (2022). Urge Incontinence. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563172

National Association for Continence. (n.d.). NAFC’s review of three popular kegel exercise apps. Retrieved November 1, 2025, from https://nafc.org/bhealth-blog/nafcs-review-of-3-popular-kegel-apps

Pang, H., Lv, J., Xu, T., Li, Z., Gong, J., Liu, Q., Wang, Y., Xia, Z., Li, Z., Li, L., & Zhu, L. (2022). Incidence and risk factors of female urinary incontinence: A 4-year longitudinal study among 24,985 adult women in China. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 129(4), 580–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16936

Patel, U., Godecker, A., Giles, D., & Brown, H. (2022). Updated prevalence of urinary incontinence in women: 2015–2018 national population-based survey data. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, 28(4), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/spv.0000000000001127

Poise®. (n.d.). Impressa® bladder supports for women. Retrieved November 1, 2025, from https://www.poise.com/en-us/products/impressa/introduction

Shenot, P. J. (2025). Urinary incontinence in adults. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/genitourinary-disorders/voiding-disorders/urinary-incontinence-in-adults

Teixeira, N. V., Colla, C., Sbruzzi, G., Mallmann, A., & Paiva, L. L. (2018). Prevalence of urinary incontinence in female athletes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Urogynecology Journal, 29(12), 1717–1725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3651-1

Todhunter-Brown, A., Hazelton, C., Campbell, P., Elders, A., Hagen, S., & McClurg, D. (2022). Conservative interventions for treating urinary incontinence in women: An overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd012337.pub2

Vaughan, C. P., & Markland, A. D. (2020). Urinary incontinence in women. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(3), ITC17–ITC32. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC202002040

Welk, B., & McArthur, E. (2020). Increased risk of dementia among patients with overactive bladder treated with an anticholinergic medication compared to a beta-3 agonist: A population-based cohort study. BJU International, 126, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15040

Winkelman, W. D., & Elkadry, E. (2021). An evidence-based approach to stress urinary incontinence in women: What’s new? Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 64(2), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1097/grf.0000000000000616

Wong, J., & Ramm, O. (2021). Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 64(2), 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000615

World Health Organization. (2017). Evidence profile: Urinary incontinence. In Integrated Care for Older People: Guidelines on Community-level Interventions to Manage Declines in Intrinsic Capacity. Author. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MCA-17.06.08

Powered by Froala Editor