About this course:

This module addresses cultural influences on health and illness, describes the position of providing culturally competent nursing care to diverse populations, and identifies current evidence-based practice guidelines for culturally competent care.

Course preview

Cultural Competency and Humility

This module addresses cultural influences on health and illness, describes the position of providing culturally competent nursing care to diverse populations, and identifies current evidence-based practice guidelines for culturally competent care.

Upon completion of the activity, participants will be able to:

- describe cultural influences on health and illness

- explain cultural competence and the importance of providing culturally competent care to patients

- identify current evidence-based practice guidelines for culturally competent care

- explore the alternative of cultural humility and how HCP training for this concept could look

Terms to Know

Cultural competency means the healthcare provider/professional (HCP) understands and addresses each patient’s entire cultural context within the domain of care. Culturally competent care means providing medical care that considers each patient's values, beliefs, and practices (Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, n.d.). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines the delivery of culturally competent care as respectful and receptive to the health ideas, practices, cultural, and linguistic needs of diverse patients (Nair & Adetayo, 2019). Similarly, the following terms may also be used to describe care that is delivered within the context of a patient's culture:

- Culturally sensitive care means the HCP is aware and knowledgeable of different cultures and their prevalence in the local community (Potter et al., 2023).

- Culturally appropriate care means the HCP applies their knowledge of a client's culture to their care delivery (Potter et al., 2023).

- Culturally congruent care is customized to the individual's culture, health-illness context, needs, values, and beliefs (Leininger, 1999).

- Transcultural nursing means providing health care based on patients’ culture, values, health-illness context, and beliefs (Leininger, 1999).

Culture is "the integrated pattern of human knowledge, belief, and behavior that depends upon the capacity for learning and transmitting knowledge to succeeding generations" (Merriam-Webster, 2020). Potter and colleagues (2023) highlight norms, values, and traditions passed down from generation to generation in their definition of culture.

Cultural awareness is the ability to investigate and understand the differences between beliefs, perceptions, values, and traditions within one’s culture and those of other cultures (Assessment Technologies Institute [ATI], 2022).

A disability is any condition of the mind or body that creates difficulties in performing activities and/or interacting with the world (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Faith is a strong belief in something or an unseen higher power (Potter et al., 2023).

A health disparity is a difference between populations in the achievement of full health potential. It can be measured using the incidence, prevalence, mortality, burden of disease, and other adverse outcomes. It is influenced by sex and gender, sexual identity, ethnicity/race, age, disability, socioeconomic status, and geographic location (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017).

Health equity is defined as attaining the highest level of health for all people (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.-a).

Health literacy is the ability to process, obtain, and comprehend basic health information and the services needed to make informed health decisions (Potter et al., 2023).

LGBTQIA stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other sexual and gender minorities (National LGBTQIA+ Health and Education Center, 2020).

Religion is a belief system practiced to express spirituality (Potter et al., 2023).

Spirituality refers to connectedness within oneself, others, the environment, and an unseen higher power (Potter et al., 2023).

Introduction

Culture comprises a group of people who share beliefs, faith systems, values, and ways of thinking or acting; it also provides a framework for defining illness. Culture is a major part of a patient’s life, influencing how they perceive and receive health care (ATI, 2022). Patients vary widely in their cultural and spiritual attributes, such as their communication style, language, customs, norms and traditions, religion, art, music, dress, health beliefs, and practices. HCPs must identify and address their preconceptions before providing optimal patient care (Potter et al., 2023).

Additionally, ethnicity, race, gender, sexual orientation, and immigration status are all essential considerations in the expanding view of culture. Nurse theorist Madeleine Leininger (1999) explained transcultural nursing as a comparative study of cultures to understand their similarities and differences. In essence, transcultural nursing aims to provide culturally congruent care that is meaningful and compatible with the patient's values. For example, rather than advising all patients to take medications simultaneously during the day, a nurse can provide culturally congruent care by learning about each patient's lifestyle and customizing their recommendations to fit this lifestyle. Through culturally competent care, an HCP can focus on offering personalized care (Leininger, 1999). In other words, culturally competent care is a process by which HCPs provide individualized care, crucial to reducing healthcare disparities (Albougami et al., 2016).

Since culture influences health beliefs and health practices (refer to Table 1), HCPs should be mindful of patient’s religious and spiritual needs. Religion and spirituality can influence a patient’s decision about diet, medicines, modesty, and preferred gender/sex of HCP; some religions have strict prayer times that can interfere with medical treatment. It’s imperative that HCPs provide patients the opportunity to discuss their religious and spiritual beliefs and include this in the plan of care (Swihart et al., 2023). Table 1 identifies cultural groups, specific healthcare beliefs and responses to illness common within these groups, and related implications for HCPs.

Table 1

Common Religious Beliefs about Health Information

Cultural Group | Healthcare Beliefs and Response to Illness | Implications for HCPs |

Hinduism (0.7% of the US population) |

|

|

Christianity (70.6% of US population) |

|

|

Islam (0.9% of US population) |

|

|

Judaism (1.9% of US population) |

|

|

Buddhism (0.7% of US population) |

|

|

(Swihart et al., 2023; Potter et al., 2023)

The relationships between an HCP's and patient's knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors are ongoing and multidimensional. An HCP's behaviors are affected by their knowledge of a particular culture and its impact on their beliefs, their attitudes towards certain age or racial groups (including unconscious biases and stereotypes), and their skills in intercultural communication (including their ability to function with a medical interpreter). HCPs are indoctrinated into the culture of Western medicine early, with its characteristic language, customs, behaviors, and even attire, and may lose their sense of human connection with their patients, focusing more on the measurement and standardization of laboratory and diagnostic tests, pharmacological treatments, and surgical procedures. These coalesce into exhibited behaviors by the HCP, such as communication style, respect, sensitivity, shared decision-making, and self-management support. Similarly, a patient's behaviors are affected by their knowledge (i.e., English language and health literacy); attitudes towards Western medicine, HCPs, and protective truthfulness; and their skills regarding communication with HCPs and navigation of the US healthcare system. Protective truthfulness is the concept espoused in many cultures that the patient deserves to be protected from the harsh reality of the clinical information by a close group of trusted family, friends, or surrogates who act collectively to filter information for the patient and/or collectively make treatment decisions. Acculturation also affects patient behavior, which is the "degree to which persons from a particular racial and ethnic background have incorporated the cultural attributes of the mainstream culture" (Periyakoil, 2019, p. 425). Cultures also define acceptable behaviors to communicate distress independently, and these may vary widely. All of this combines to create patient behaviors such as expression of values/preferences, informed decision-making, treatment adherence, self-advocacy, and self-management. The final complicating factor is that the HCP's and the patient's behaviors also interact and affect each other on a continuous and ongoing basis (Periyakoil, 2019).

Cultural Competency and the Importance of Providing Culturally Competent Care

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP, n.d.-a) created Healthy People (HP) to identify public health priorities for patients, communities, and organizations within the US to improve well-being and health. To assist with meeting the goals of HP, HCPs should understand the importance of health equity and some of the disparities in health care (ODPHP, n.d.-a)

According to HP 2030, healthy equity is defined as the attainment of the highest level of health for all people. A health disparity is a variation in health related to social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage (ODPHP, n.d.-b). In the US, individuals face challenges with receiving quality and stable health care due to one or more of the following factors:

- age

- race or ethnicity

- faith/religion

- socioeconomic status

- mental illness

- disability (cognitive, sensory, or physical)

- sexual orientation or gender identity

- sex/gender

- geographic location

- other characteristics that are linked to discrimination (ODPHP, n.d.-b)

There is a substantial link between social determinants of health (SDOH) and healthcare disparities in the literature. SDOH are defined as an individual’s environmental conditions that affect their quality-of-life outcomes, risks, and overall health (see Figure 1). The HP 2030 classifies the SDOH into five domains: social and community context, health care access and quality, education access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and economic stability. A patient’s SDOH and cultural factors can influence health disparities. A lack of access to health care is a crucial social determinant contributing to healthcare disparities. Research also suggests that lower socioeconomic groups have less access to care compared to higher-income groups (ODPHP, n.d.-d; Potter et al., 2023).

More than two decades ago, reports by the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2001) identified the six domains of healthcare quality: equitable, timely, efficient, safe, effective, and patient-centered. Although US health care has improved in certain areas, it still lacks equity, as evidenced by existing data (below). One of the primary goals of Healthy People 2030 is to ”eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all” (ODPHP, n.d.-b). This may be due to inadequate resources, such as access to language services, as well as poor patient-provider communication and a lack of culturally competent care (Potter et al., 2023).

An individual’s neighborhood or environment in which they live can impact their health. According to the HHS, neighborhoods in the US that have unsafe air and drinking water with a high rate of violence are most likely inhabited by racial/ethnic minorities or individuals who have low income (ODPHP, n.d.-a). Certain syndromes or illnesses can primarily affect a specific culture or group of people due to family history, inherited genetic mutations, or shared environmental factors. The non-Hispanic White (NHW) population has a higher rate of most types of cancers than Asian Americans, whereas Asian Americans have a higher incidence of liver cancer as compared to Hispanic individuals, NHWs, and non-Hispanic Black (NHB) patients. Although life expectancy and US population health have improved overall during the past 50 years, the health of members of disadvantaged groups has not improved to the same degree. The infant mortality rate for NHB patients is more than double the rate experienced by NHW patients. The mortality rate due to stroke and coronary artery disease before age 75 is higher among NHB than among NHW patients. Diabetes prevalence is higher among NHB patients, Hispanic patients, multiracial individuals, persons without a college degree, and those with a lower household income (CDC, 2020; Quiñones et al., 2019). Furthermore, approximately 61 million US adults are affected by a disability, which translates to 26% of the US population. Disabled individuals face many health disparities, such as higher rates of obesity, smoking, and inactivity; fewer preventive screenings; and higher rates of death from breast and lung cancers (CDC, 2020). Research also suggests that some subgroups of LGBTQIA+ people have more chronic conditions with a higher prevalence and an earlier onset of disabilities than individuals who do not identify as LGBTQIA+ (National LGBTQIA+ Health and Education Center, 2020). In the US, the LGBTQIA+ population has increased to 7.1%, highlighting the need for additional cultural competence to reduce healthcare disparities within this group of individuals (Jones, 2022).

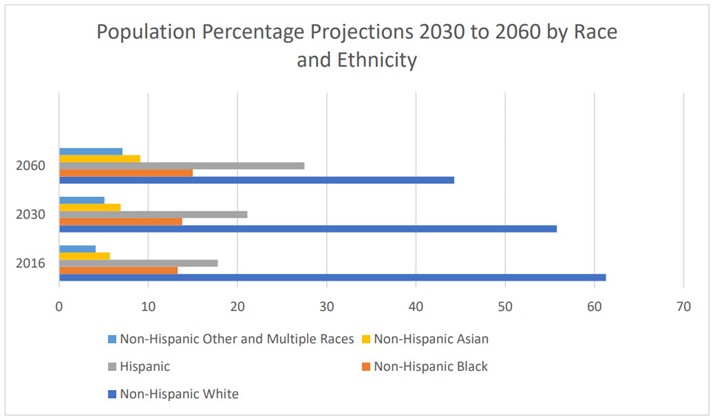

NHB adults have a higher incidence of hypertension than their NHW counterparts. Adult mortality rates related to heart disease and stroke, common chronic diseases targeted in the Healthy People 2030 initiative, are also higher among NHB adults as compared to NHW adults. Additionally, the population within these groups is expected to rise over the next four decades, as shown in Figure 2. By 2060, racial and ethnic minorities will comprise a high percentage of the older adult population.

Figure 1

Social Determinants of Health Domains that evolve around the patient.

(ODPHP, n.d.-d)

Figure 2

Racial and Ethnic Minority Demographic Projections by 2060

(Vespa et al., 2020)

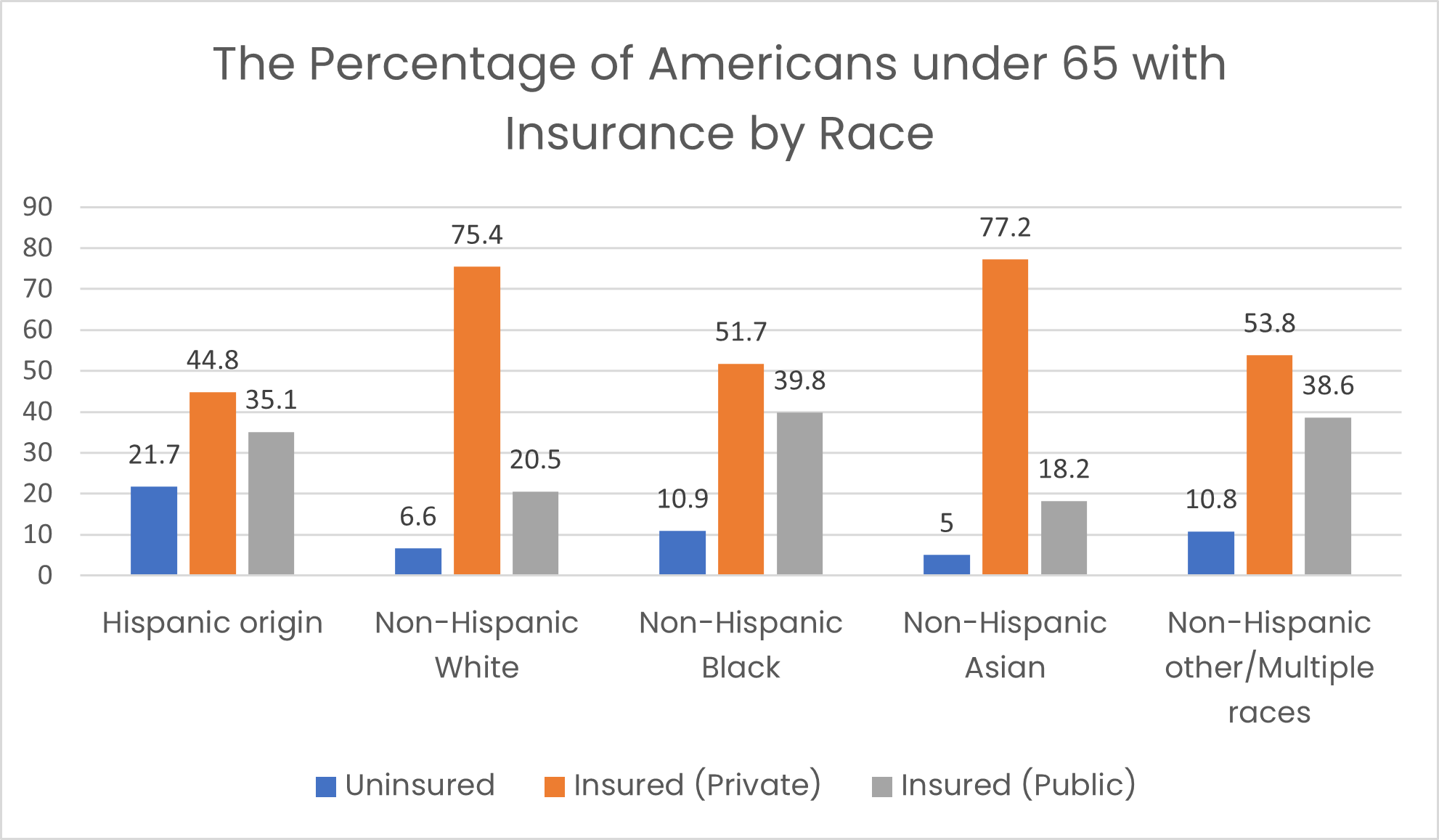

The data collected from the National Health Interview Survey in 2021 revealed that 21.7% of Hispanic, 10.9% of NHB, 6.6% of NHW, and 5% of non-Hispanic Asian adults who were less than 65 years of age lacked health insurance (see Figure 3; Cha & Cohen, 2022). A higher proportion of some minority groups do not have health insurance compared to NHWs. This lack of coverage leads to reduced access to needed care. Research demonstrates that uninsured individuals are less likely to have a regular HCP than those with insurance; this increases the risk of serious health problems. Healthy People 2030 focuses on improving dental, medical, and prescription medication insurance coverage for all (ODPHP, n.d.-a).

In the late 60s and 70s, the rate of uninsured Americans under the age of 65 was relatively stable at around 21%. Then, beginning in the 80s, this number increased to 33% by 2007 (Cohen et al., 2009). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted in 2010 to make health insurance affordable for all individuals in the US. This caused the number of uninsured Americans to decrease rapidly. In 2012, just 17% of Americans under 65 were uninsured (Adams et al., 2013). Between 2012 and 2016, this number dropped consistently to just 10.4%. The number of uninsured Americans under 65 increased again until it peaked at 12% in 2019. In 2020, 11.5% and in 2021, 10.3% of Americans under 65 were uninsured (Cha & Cohen, 2022). This 2021 decrease likely relates to the extension of the ACA with America’s Rescue Plan, which decreased the cost of health insurance coverage. A specified goal of HP 2030 is to increase insurance coverage nationwide to 92.4%, or an uninsured rate of just 7.6% (ODPHP, n.d.-c).

Figure 3

Percentage of Americans Under 65 Uninsured in 2021

(Data based on National Health Interview Survey; Cha & Cohen, 2022)

Research indicates that ethnic minority groups continue to exhibit decreased rates of healthcare utilization for preventative and diagnostic services even after reaching the age of Medicare eligibility (Quiñones et al., 2019). Factors other than the lack of insurance coverage contribute to healthcare disparities. Obstacles to literacy also influence access to and increase the cost of health care. Individuals with lower literacy skills utilize health services more frequently, which creates between 3 and 6% additional healthcare costs (Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, n.d.). Inequities in health care lead to poor health outcomes and poor patient adherence to the treatment plan and contribute to the distrust of HCPs and the healthcare system in general. Healthcare disparities are burdensome to individuals and affect community-wide economics through indirect impacts such as lost efficiency at work, sick absences, and financial stress on families (Periyakoil, 2019). By focusing on care that is culturally competent, HCPs can help to reduce healthcare disparities. Culturally competent care can enhance rapport with patients, reduce healthcare disparities and healthcare costs, as well as improve patient health outcomes and satisfaction (Jongen et al., 2018; Periyakoil, 2019).

Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines for Culturally Competent Care

Individuals should feel empowered to express their personal values regarding sexual orientation, politics, culture, and religion. Georgetown University’s National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC) published a conceptual framework for achieving cultural and linguistic competence based on the work of Cross and colleagues in 1989. Organizations should value diversity, conduct ongoing cultural self-assessments, manage the dynamics of difference, institutionalize cultural knowledge, and adapt to variety (Georgetown University NCCC, n.d.-a). To address these unique and individualized patient needs, HCPs and organizations should perform a self-assessment of their organizational culture first. Each member of the healthcare team must identify their values and beliefs to avoid imposing them on others. The NCCC provides one option for this, entitled the Cultural and Linguistic Competence Health Practitioner Assessment (CLCHPA). This self-guided activity is a validated measure that takes about 30 minutes to complete. The score report provided at the end provides information on how your responses compare to a sample of 2,500 HCPs analyzed (in 2010) in relation to three factors: knowledge of diverse populations, adapting practice for diverse patient populations, and health promotion in diverse communities. It also provides feedback on linguistic competence (ability to communicate effectively despite diverse patient populations with varying degrees of English and medical literacy) and knowledge of health disparities that impact diverse patient populations (Georgetown University NCCC, n.d.-b). Periyakoil (2019) observes that self-assessment can identify barriers to understanding other cultures. Potential barriers to culturally competent care include the following:

- stereotypes based on ethnicity or race

- cultural differences

- personal or racial bias

- language barriers

- lack of culturally competent care training

- lack of inclusiveness training (Periyakoil, 2019)

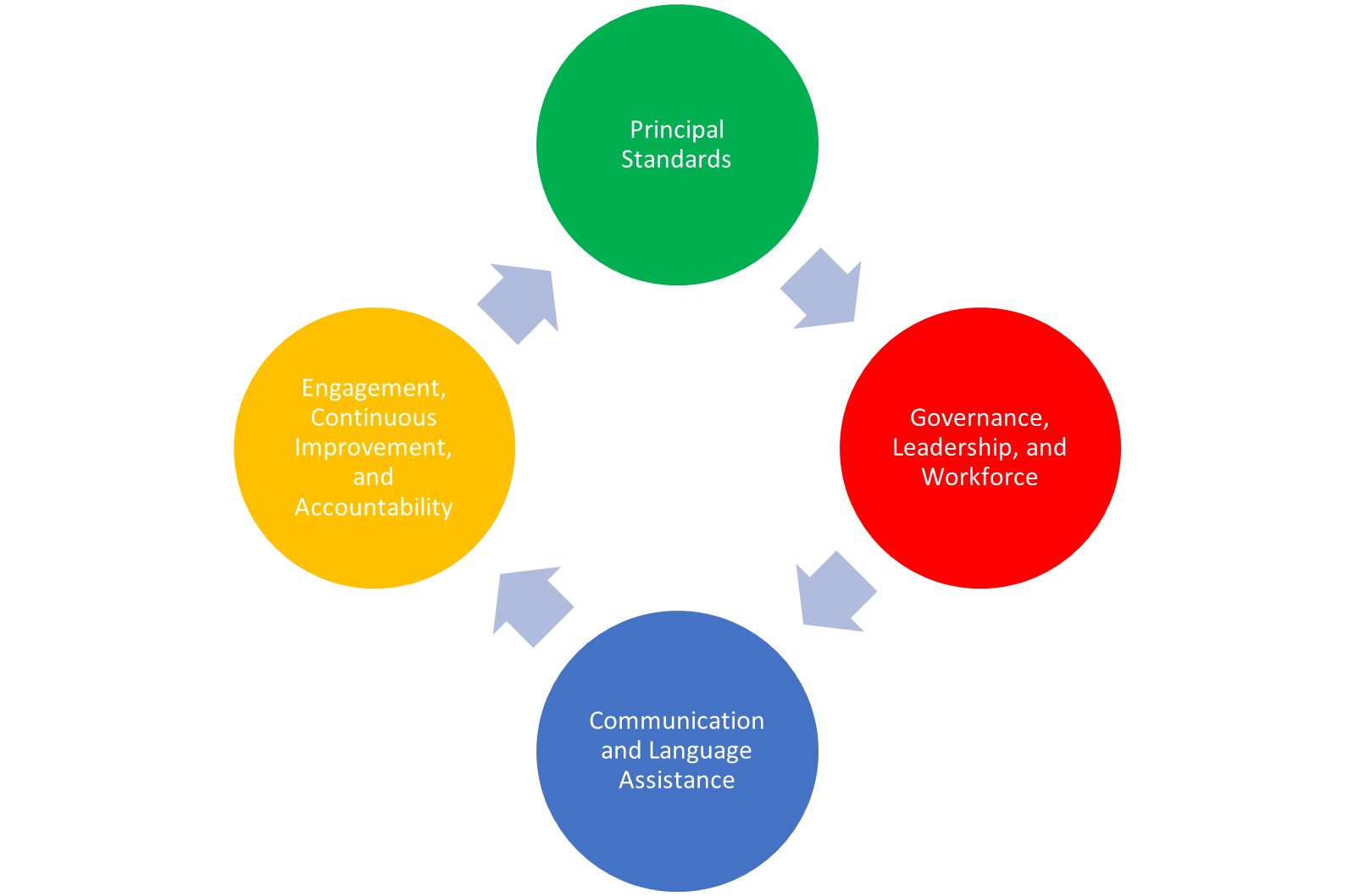

Culturally competent care begins with collecting a patient’s history, assessing health literacy, performing a culturally based physical assessment, and providing patient education. The HCPs must ensure that communication is effective. A common health system-related barrier is a lack of culturally tailored services, including access to medical interpreters. Healthcare organizations and HCPs need to cooperate to develop the appropriate knowledge, attitude, and skills to deliver the best care to all patients. The importance and value of HCP training regarding cultural competence cannot be overstated. HCPs must listen, understand, and then communicate with their patients using respectful intercultural communication, and this is a skill that can be modeled, practiced, and improved upon. This training should be immersive and skill-oriented (Periyakoil, 2019). Many healthcare organizations offer guidance on providing culturally competent care. One of the pioneers of this effort in the US is the HHS Office of Minority Health (OMH). The OMH developed the culturally and linguistically appropriate standards (CLAS) in 2000 and updated them in 2013. The intention of the enhanced CLAS standards is to establish a blueprint for advancing health equity, improving quality, and eliminating disparities. CLAS standards strive to create a culturally competent environment for healthcare organizations, HCPs, and patients (OMH, n.d.). Table 2 lists the CLAS standards, and Figure 4 graphically depicts the CLAS standards in practice.

Table 2

CLAS Standards to Achieve Cultural Competence

CLAS Standards | Action Plan |

Principal standard | Provide effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care/services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs, practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other communication needs. |

Governance, leadership, and workforce |

|

Communication and language assistance |

|

Engagement, continuous improvement, and accountability |

|

(HHS, 2013; OMH, n.d.)

Figure 4

Diagram of a Continuous Process of Implementing and Evaluating CLAS Standards in an Organization to Achieve Cultural Competence

(HHS, 2013; OMH, n.d.)

Culturally competent care promotes health and healing. Below are two examples of delivering culturally competent care through the application of CLAS standards:

- If a patient values spirituality, find a way to integrate spiritual and medical practices for healing.

- If a patient's culture dictates that a family member must participate in all medical decisions, confirm the patient’s consent, and then involve the family member in the care of that patient (OMH, n.d.).

Similarly, transcultural nurse theorist Larry Purnell (2002) provides a model for cultural competence that highlights the following 12 cultural domains:

- overview/heritage

- communication

- family roles and organization

- workforce issues

- biocultural ecology

- high-risk behaviors

- nutrition

- pregnancy and childbearing

- death rituals

- spirituality

- healthcare practices

- healthcare practitioners (Potter et al., 2023)

Purnell's model includes the foundation for understanding various cultural attributes and highlights patients' characteristics, such as their experiences and beliefs about health care and illness (Potter et al., 2023). Purnell (2002) considered these 12 domains to be crucial in helping HCPs determine the traits and characteristics of different ethnic groups and deliver culturally competent care. The Purnell model consists of concentric circles: the inner circle represents the individual, the middle circle represents the family, and the outermost circle represents the community/global society. It provides a comprehensive view of culture and helps HCPs ask critical questions to better understand patients' perspectives, culture, and health or illness beliefs (Purnell, 2002).

Assessing a patient’s health literacy will determine how best to plan and present information to the patient. According to Potter (2023), health literacy is defined as the degree to which a patient can process, gather, and comprehend basic health information to make decisions about their health care. To assess health literacy, the HCP should observe the patient’s behavior and use reliable tools such as The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM-SF) or the Short Assessment of Health Literacy (SAHL-S&E; Potter et al., 2023).

HCPs should complete a comprehensive cultural assessment to understand each patient's worldview and willingness to receive care. There are several tools available to assist HCPs with providing patient-centered and culturally competent care. Research suggests that HCPs ask patients open-ended questions using Kleinman's explanatory model to elicit the patient's perception of illness and how it should be treated. These open-ended questions include (Potter et al., 2023):

- What do you call your problem?

- What do you think caused the problem?

- When did it start?

- Why do you think it started?

- How does illness affect you?

- What are your concerns?

- How should your illness be treated?

Another potential tool is the 4 Cs of Culture by Slavin, Galanti, and Kuo (n.d.) to perform a cultural assessment. The 4 Cs are call, cope, concerns, and cause. The HCP should ask open-ended questions based on the 4Cs to perform a cultural assessment. Examples include (Slavin et al., n.d.):

- What do you call the problem you are having now?

- How do you cope with the problem?

- What are your concerns regarding the problem?

- What do you think caused the problem?

Lastly, HCPs should use practical communication skills to connect with patients in a culturally congruent way. A few authors have developed communication mnemonics; one of the most frequently used is LEARN, which stands for listen, explain, acknowledge, recommend, and negotiate. The HCP should listen with empathy to the patient's explanation of the presenting problem. Next, the HCP should explain their perception of the problem to the patient, acknowledge and discuss cultural differences and similarities with the patient, and then recommend treatment while involving the patient. Lastly, the HCP negotiates an agreement that incorporates pertinent aspects of the patient's culture into their care (Potter et al., 2023).

The use of medical interpreters (MIs) is a skill that should be covered/reviewed with HCPs as a component of cultural competency training. The HCP should assess whether an MI is needed and discuss this need with the patient to ensure they consent to the use of an MI. When using an MI, HCPs should brief the MI prior to the appointment regarding the most crucial aspects before the patient arrives to ensure efficient transfer of information. When using an MI, it is important to remember the following (Potter et al., 2023):

- MIs utilize conduit-style interpretation, which is literal translation delivered in the first person without clarification, summarization, or omission.

- HCPs should speak in short sentences and avoid extensive use of medical jargon except when necessary.

- HCPs should sit across from the patient at eye level and speak directly to the patient, allowing a clear and unobstructed view of the patient and the HCP by the MI.

- When doing a physical examination, a curtain should be used to protect the patient's privacy while still allowing the MI the ability to hear and continue to interpret during the examination.

- A short debrief with the MI following the examination should occur, thanking them for their assistance; the medical record should include the MI's name and any other prudent agency contact information.

Alternative training may include how best to delegate responsibilities to other HCPs when time and resources are scarce and the use of community health workers (CHWs). CHWs are community members with some health promotion/services training, although they are not licensed HCPs. CHWs may be able to meet patients at their homes or within their communities and often share cultural, ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, or other values and life experiences in common with the patient. CHWs may be volunteers or paid employees of a healthcare system or community organization. They may be able to play a crucial role in scheduling appointments, arranging transportation, providing interpretation services, tailoring patient education, and facilitating treatment plan adherence. The Stanford In-Reach for Successful Aging and End-of-Life (iSAGE) mini-fellowship is an example of a training program designed for CHWs. This program was able to achieve the goals of care, improve patient satisfaction, and reduce healthcare utilization and cost over time with the use of well-trained CHWs (Periyakoil, 2019).

Potential Pitfalls and Cultural Humility

Lekas and colleagues (2020) suggest that HCPs and organizations think of culture as “a changing system of beliefs and values shaped by our interactions with one another, institutions, media and technology, and by the socioeconomic determinants of our lives”. They suggest that it is not stagnant and, therefore, cannot be fully comprehended by any HCP or taught in any seminar. They also posit that a culture does not uniformly apply to all members of any particular group. The idea that a core set of values and beliefs can be shared by all members of any group is reductionist and suggestive of a social stereotype that could be damaging and even stigmatizing. This antiquated perspective suggests that all HCPs are non-Hispanic White heteronormative males who speak English, and anything that deviates from this perspective is other and must be explained to be understood. Competency training should avoid focusing on outlining a prototypical non-White patient population who are presumed to share a common set of experiences and principles based solely on their shared race/ethnicity. This method of training HCPs in cultural competence may reinforce implicit bias towards patients. Everyone (patient or otherwise) is also composed of various layers of characteristics (class, gender, sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.). To address a patient primarily based on only one of those layers assumes a predominance that may be false (Lekas et al., 2020).

In their research, Lekas and colleagues found marked variability in the scope, content, and length of Competency training, leading to a general lack of clarity. HCP training over the last two decades has also not translated into improvements in patient satisfaction or health outcomes (decreased disparities) despite showing enhanced HCP knowledge. Even the enhanced knowledge in the evidence is heterogeneous and widely varied. Instead, this group suggests focusing on cultural humility in lieu of competence. They define this as “an orientation towards caring for one’s patients that is based on self-reflexivity and assessment, appreciation of patients’ expertise on the social and cultural context of their lives, openness to establishing power-balanced relationships with patients, and a lifelong dedication to learning. Cultural humility means admitting that one does not know and is willing to learn from patients about their experiences while being aware of one’s own embeddedness in culture(s).” The term competence indicates that the learner may reach an enhanced level of understanding or mastery, while the term humility suggests that the learner establishes an approach that is person-centered, open, intrapersonal, and interpersonal (Lekas et al., 2020). Similarly, the CDC defines cultural humility as an

active engagement in an ongoing process of self-reflection in which individuals seek to:

- examine their personal history/background and social position related to gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, profession, education, assumptions, values, beliefs, biases, and culture, and how these factors impact interpersonal interactions.

- reflect on how interpersonal interactions and relationships are impacted by the history, biases, norms, perception, and relative position of power of one’s professional organization.

- gain deeper realization, understanding, and respect of cultural differences through active inquiry, reflection, reflexivity, openness to establishing power-balanced relationships, and appreciation of another person’s/community’s/population’s expertise on the social and cultural context of their own lives (lived experience) and contributions to public health and well-being.

- recognize areas in which they do not have all the relevant experience and expertise and demonstrate a nonjudgmental willingness to learn from a person/community/population about their experiences and practices (CDC, 2022)

Developing cultural humility, just as with cultural competence, should begin by exploring and taking inventory of our own life experiences, biases, beliefs, and cultural influences to first recognize where we stand in our own perspective. Once that has occurred, training then focuses on HCPs remaining humble, open, respectful, and person-centered. This position may counterbalance the inherent power dynamics of the traditional patient-provider relationship, lead to a more equal power structure, and thus improve communication and, eventually, quality of care. Training in cultural humility should be process-oriented in place of previous content-oriented competency training. To avoid repeating similar past mistakes, the authors suggest that cultural humility be clearly defined and measured as a concept prior to widespread training, without the use of spin-off concepts (e.g., cultural sensitivity/respect/safety). They also suggest that training effectiveness be assessed from the perspective of the HCP as well as the patient to adequately gauge value (Lekas et al., 2020).

The training developed by Lekas and colleagues begins with the CLAS standards, specifically the domains of culture, structure, and health equity. They suggest the use of Harvard University’s Implicit Association Test (IAT) to explore HCPs’ implicit and explicit biases. They discuss the Health Lifestyle Model as a theoretical framework for health habitus. Health habitus directly influences people’s health behaviors and eventually becomes their health lifestyle. This habitus is directly influenced by the individual’s culture, social standing, and choices. Training should allow participants to explore their own health habitus and then participate in group discussions to facilitate self-awareness and humility. HCPs should be counseled to remain open and flexible when interviewing patients to assess their health habitus, as opposed to a controlling or authoritative interviewing style. Patients should guide this discussion, not the HCP. The group is currently undergoing a process and outcomes evaluation of their training model (Lekas et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Cultural competence is a fundamental part of health care that can increase patient satisfaction and overall quality of care, but healthcare disparities inflate costs and contribute to poor population health. Culturally competent HCPs and organizations can help eliminate health disparities and improve the quality of care. To achieve cultural competence, HCPs need to perform a comprehensive cultural assessment on patients by using an explanatory model to understand each patient's views on health and illness. Cultural competence is an ongoing, long-term process for HCPs and organizations.

Case Studies

Case Study #1

Mr. Emil Prado is a 45-year-old Hispanic man who is overweight and was diagnosed with diabetes two years ago. He has been on insulin since last month. Mr. Prado has not received any formal education. The patient worked as a roofer until recently but lost his job after the company downsized. Mr. Prado does not have any other job training. As a result, he has not secured another job. The patient has no health insurance, cannot pay for rent or prescriptions, and recently became homeless.

This morning, Mr. Prado arrived at the emergency department (ED) with a blood glucose (BG) level of 322 mg/dL and a hemoglobin A1C of 11%. Upon reviewing the chart, the RN notices the patient has been noncompliant with care and had several repeated admissions to the ED recently.

1. Based on Kleinman's explanatory model, what questions should the nurse ask Mr. Prado during a cultural assessment?

Answer:

- What do you call your problem?

- What do you think caused the problem?

- When did it start?

- Why do you think it started?

- How does illness affect you?

- What are your concerns?

- How should your sickness be treated?

2. Which social determinants of health will the nurse likely discover while conducting a cultural assessment with Mr. Prado?

- Answer: Some of the social determinants highlighted in the case are:

- lack of resources to meet daily needs such as safe housing, food, etc.

- lack of formal education

- gap in employment

- lack of health insurance

- lack of resources to pay for prescriptions

3. Based on a cultural assessment, the nurse discovers that Mr. Prado doesn't have insurance or a place to stay. What should the nurse do to provide resources to the patient?

- Answer: The nurse should consult with the social worker and case manager of the facility. The social worker may be able to provide information about a community health center that offers a BG management program, housing, and unemployment resources. The nurse should also collaborate with the patient to define a realistic way to manage his diabetes, given his challenging circumstances.

Case Study #2

Daisy is an RN at a nephrology clinic. Amal arrives 30 minutes late for his appointment. Daisy asks Amal if he encountered any problems that caused him to be late. Amal replies, "No, nothing significant." Daisy is frustrated and reminds Amal that timeliness is expected. Amal is offended by Daisy's lack of respect and leaves the clinic, thinking he is no longer welcome as a patient.

- How would you advise the RN to handle this situation differently in the future?

- Answer: Explain to the RN that in some cultures, time is seen as a valuable, finite resource. Other cultures may have a more flexible concept of time. In the future, instead of acting frustrated, the RN can educate each patient on the importance of being on time for their appointment.

References

Adams, P. F., Kirzinger, W. K., and Martinez, M. E. (2013). Summary health statistics for the US population: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 10(259). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_259.pdf

Albougami, A. S. (2016). Comparison of four cultural competence models in transcultural nursing: A discussion paper. International Archives of Nursing and Health Care, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.23937/2469-5823/1510053

Assessment Technologies Institute Testing (2022). RN Engage Fundamentals, Version 2. www.atitesting.com.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, September 15). Disability and health overview. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, August 8). Principle 1: Embrace cultural humility and community engagement. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/equity/guide/cultural-humility.html

Cha, A. E., and Cohen, R. A. (2022). Demographic variation in health insurance coverage: United States, 2021. National Health Statistics Reports Number (177) https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr177.pdf

Cohen, R. A., Makuc, D. M., and Powell-Griner, E. (2009). Health insurance coverage trends, 1959-2007: Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr017.pdf

Cross, T. L., Bazron, B. J., Dennis, K. W., & Issacs, M. R., (1989). Toward a culturally competent system of care. Georgetown University Development Center. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/towards-culturally-competent-system-care-monograph-effective

Georgetown University Health Policy Institute. (n.d.). Cultural competence in health care: Is it important for people with chronic conditions? Retrieved August 2023, from https://hpi.georgetown.edu/cultural/

Georgetown University National Center for Cultural Competence. (n.d.-a). Conceptual frameworks, models, guiding values, and principles. Retrieved August 2023 from https://nccc.georgetown.edu/foundations/framework.php

Georgetown University National Center for Cultural Competence. (n.d.-b). Cultural and linguistic competence health practitioner assessment. Retrieved August 2023 from https://www.clchpa.org/

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. (2001). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press.

Jones, J. (2022). LGBT identification in US ticks up to 7.1%. https://news.gallup.com/poll/389792/lgbt-identification-ticks-up.aspx

Jongen, C., McCalman, J., & Bainbridge, R. (2018). Health workforce cultural competency interventions: A systematic scoping review. BMC health services research, 18(1), 232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5

Leininger, M. M. (1999). What is transcultural nursing and culturally competent care? Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 10(1), 9–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/104365969901000105

Lekas, M., Pahl, K., & Lewis, C. F. (2020). Rethinking cultural competence: Shifting to cultural humility. Health Services Insights. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920970580

Merriam-Webster. (2020). Definition of culture. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/culture

Nair, L., & Adetayo, O. A. (2019). Cultural competence and ethnic diversity in healthcare. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery – Global Open, 7(5), e2219. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002219

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States. (2017). Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. The state of health disparities in the United States. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425844/

National LGBTQIA+ Health and Education Center. (2020). LGBTQIA+ glossary of terms for healthcare teams. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/publication/lgbtqia-glossary-of-terms-for-health-care-teams

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.-a). Healthy People 2030. Retrieved August 2023 from https://health.gov/healthypeople

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.-b) Healthy People 2030: Health equity in Healthy People 2030. Retrieved August 2023 from https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-equity-healthy-people-2030

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.-c) Healthy People 2030: Increase the proportion of people with health insurance — AHS‑01. Retrieved August 2023 from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/health-care-access-and-quality/increase-proportion-people-health-insurance-ahs-01

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.-d) Healthy People 2030: Social determinants of health. Retrieved August 2023 from www.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

Office of Minority Health. (n.d.). The national CLAS standards. Retrieved August 2023 from https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas/standards

Periyakoil, V. S. (2019). Building a culturally competent workforce to care for diverse older adults: Scope of the problem and potential solutions. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 67, S423–S432. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15939

Potter, P. A., Perry, A. G., Stockert, P., & Hall, A. (2023). Fundamentals of nursing (11h ed.). Elsevier

Purnell, L. (2002). The Purnell model for cultural competence. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(3), 193-196. https://doi.org/10.1177/10459602013003006

Quiñones, A. R., Botoseneanu, A., Markwardt, S., Nagel, C. L., Newsom, J. T., Dorr, D. A., & Allore, H. G. (2019). Racial/ethnic differences in multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PloS One, 14(6), e0218462. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218462

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). National CLAS standards: Culturally and linguistically appropriate services. https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas

Slavin, S., Kuo, A. & Galanti, G. A. (n.d.) The 4Cs of culture. Retrieved August 2023, from https://ggalanti.org/the-4cs-of-culture/

Swihart, D. L., Yarrarapu, S. N. S., and Martin, R. L. (2023). Cultural religious competence in clinical practice. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493216/

Vespa, J., Medina, L., & Armstrong, D. (2020). Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.html