About this course:

This course reviews relevant terminology and statistics related to suicide, including the increasing prevalence of nurse and other healthcare professional (HCP) suicide. It also examines the risk factors for suicide and the clinical manifestations of burnout, compassion fatigue (CF), and secondary traumatic stress (STS) in nurses. Finally, this course will review screening for suicide and prevention strategies that can reduce the incidence of suicide, specifically for nurses and other HCPs. This course satisfies the one-time, two-contact hour requirement for continuing education within Kentucky for nurses educated outside of the state or before August of 2025, as stated in 201 KAR 20:215.

Course preview

Suicide Prevention for Kentucky Nurses

This course reviews relevant terminology and statistics related to suicide, including the increasing prevalence of nurse and other healthcare professional (HCP) suicide. It also examines the risk factors for suicide and the clinical manifestations of burnout, compassion fatigue (CF), and secondary traumatic stress (STS) in nurses. Finally, this course will review screening for suicide and prevention strategies that can reduce the incidence of suicide, specifically for nurses and other HCPs. This course satisfies the one-time, two-contact hour requirement for continuing education within Kentucky for nurses educated outside of the state or before August of 2025, as stated in 201 KAR 20:215.

Upon completion of this module, learners will be able to:

- review relevant terminology and statistics related to suicide in the general population and among HCPs

- identify the risk and protective factors contributing to suicide, identify warning signs of those at risk for suicide, and the most common means of suicide

- discuss the components of a suicide risk assessment, determine the level of risk, and identify evidence-based tools and interventions corresponding to each risk level

- describe the clinical manifestations of burnout, CF, and STS among HCPs

- discuss various strategies for the prevention of suicide in the general population and among HCPs

Suicide is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon involving various risk factors and warning signs. It is a preventable public health problem with a devastating psychological impact on loved ones and the community. While statistical data regarding suicide and suicide attempts vary based on race, gender, age, and other characteristics, suicide can occur among all demographic groups. Nurses must understand the defining features, risk factors, and warning signs for suicidal behaviors, as well as the critical components of suicide risk assessment. To combat this growing public health problem, timely, evidence-based interventions must become the standard of care across all health care settings (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2025; Moutier, 2024; Tiesman et al., 2021). Nurses should be aware of the following terms related to suicide:

- suicide: death caused by self-directed injurious behavior and the intent to die due to the behavior

- suicidal behavior: a term encompassing suicide attempts and suicidal ideation

- suicide attempt: a nonfatal, self-directed, potentially injurious act intended to result in death that may or may not result in injury

- suicidal ideation: thoughts about killing oneself that may include a specific plan

- suicide threat: verbalizing intent of self-injurious behavior intended to lead others to believe that one wants to die, despite no intention of dying

- suicide gesture: self-injurious behaviors intended to lead others to believe that one wants to die despite no intention of dying

- non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI): self-injurious behavior characterized by the deliberate destruction of body tissue in the absence of any intent to die and for reasons that are not socially sanctioned

- suicide means: an instrument or object used to carry out a self-destructive act, such as weapons, chemicals, medications, or illicit drugs

- suicide methods: actions or techniques that result in an individual inflicting self-directed harmful behavior, such as an overdose (Moutier, 2024; National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2025; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023; Soreff et al., 2023)

Epidemiology

Suicide is the 11th leading cause of death in the United States, and is the 2nd leading cause of death among those aged 25 to 34. More years of potential life are lost to suicide than to nearly any other cause, except for heart disease, cancer, or unintentional injury. There are nearly twice as many suicides (47,476) than homicides (24,849) in the United States annually. Suicide rates increased by 37% between 2000 and 2018, then decreased by 5% between 2018 and 2020, and peaked again in 2022. In 2022, more than 49,000 people in the United States died from suicide. On average, 132 people die by suicide daily, and one person dies every 10.7 minutes (one individual assigned male at birth every 13.5 minutes, and one assigned female every 51.2 minutes). There are 3.8 deaths by suicide among those assigned male at birth for every single death among those assigned female. According to the American Association of Suicidology (AAS), White individuals assigned male at birth have the highest suicide rates (26.8 per 100,000), followed by non-Hispanic Latinos (16.3 per 100,000), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders (15.8 per 100,000), and Black individuals assigned male at birth (14.8 per 100,000). Groups that have lower rates of suicide include Hispanic/Latino individuals (8.1 per 100,000), followed by White individuals assigned female at birth (6.8 per 100,000), people os Asian heritage (6.7 per 100,000), and Black individuals assigned female at birth (3.5 per 100,000). Suicide rates are highest amongst middle-aged adults (45 to 64 years, 18.8 per 100,000), followed by older adults (65 years and older, 17.6 per 100,000), and young adults (15 to 24 years, 13.5 per 100,000) in the United States (AAS, 2025; CDC, 2024d; NIMH, 2025).

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents aged 10 to 14 and the third leading cause of death for those aged 15 to 25. For adolescents aged 10 to 24, suicides account for 15% of all deaths (11.0 per 100,000). Suicide rates among this age group have increased by 52.2% between 2000 and 2021. Indigenous populations are the most prominently affected adolescent subgroup (31 per 100,000 deaths). Adolescents assigned male at birth have a higher rate of death by suicide compared to those assigned female, while adolescents assigned female have a higher rate of suicide attempts compared to those assigned male. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed an increasing prevalence of major depressive episodes (MDEs) among adolescents that correspond to the rise in suicide deaths among this age group. The percentage of MDEs increased from 5.5% (1.4 million people) in 2006 to 18% (4.5 million people) in 2023 (AAS, 2025; CDC, 2025; NIMH, 2025; SAMHSA, 2024a; United Health Foundation,...

...purchase below to continue the course

Studies have demonstrated that suicide rates are higher in states with more gun ownership and that increased firearm suicides drive these heightened rates. Given this finding, it is not surprising that western US states with the fewest firearm laws comprise the top five highest suicide rates: Alaska (28.1 per 100,000), Montana (27.4 per 100,000), Wyoming (26.9 per 100,000), Idaho (23.4 per 100,000), and New Mexico (23.1 per 100,000). Following firearms (56.64%), the most common methods of suicide include suffocation (24.75%) and poisoning (12.43%). While individuals assigned male at birth are more likely to attempt suicide with more lethal methods, such as firearms or suffocation, those assigned female are more likely to use poison. Those with substance use disorders (SUDs) are six times more likely to die by suicide than the general population. Suicide and nonfatal self-harm also inflict a tremendous economic burden on society, costing more than $500 billion annually in medical costs and lost work time (AAS, 2025; CDC, 2024a; Studdert et al., 2020).

Self-injurious behavior accompanied by any intent to die is classified as a suicide attempt. Nurses and society must err deliberately on the side of caution by viewing debatable behaviors as suicidal. While individuals assigned male at birth are more likely to die by suicide, those assigned female are 3 times more likely to attempt suicide. Still, it is challenging to determine the exact number of attempted suicides in the United States since there is a lack of all-inclusive databases or tracking mechanisms. Data are primarily compiled through self-reported surveys and ICD-10-CM billing codes. Due to the stigma associated with suicide attempts, they are greatly underreported. According to SAMHSA (2024a), 12.8 million Americans aged 18 or older reported having serious thoughts of suicide, 3.7 million made suicide plans, and 1.5 million attempted suicide. These numbers translate to a suicide attempt every 23 seconds, and 25 attempts for every death by suicide across the nation (100 to 200:1 for young adults and 4:1 for older adults). People who survive a suicide attempt may experience serious injuries and long-term health consequences. Many survivors experience high levels of psychological distress for lengthy periods after the initial exposure (AAS, 2025; CDC, 2024a, 2024d).

Suicide Statistics Among HCPs

As suicide rates have continued to increase in the United States over the last three decades, various disparities have been found based on race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, and other factors. In addition, some occupations are known to have higher rates of suicide, including construction, transportation and warehousing, protective services, and HCPs. Occupational stressors can place HCPs at an increased risk of depression and suicide. In a 2019 systematic review that included over 60 studies, the researchers found physicians at significant risk for suicide, with physicians assigned female at birth at particularly high risk (Dutheil et al., 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the mental wellness of HCPs. Mental Health America (MHA) surveyed over 5,000 HCPs (i.e., nurses, physicians, support staff, community-based HCPs, emergency medical technicians [EMTs]/paramedics, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) to assess burnout and stress between March and April of 2022. The survey revealed that 91% of HCPs were experiencing stress, and 81% reported exhaustion and burnout. In addition, 86% of those surveyed were experiencing anxiety, 77% were experiencing frustration, and 77% reported being overwhelmed (MHA, 2022).

Although there is significant research documenting burnout, compassion fatigue (CF), and stress among nurses, there has been less attention to suicide rates. Recently, there has been a call to action to highlight the high suicide rates among nurses in the United States (Sudheimer et al., 2024). Davidson and colleagues (2020) published the results of a longitudinal analysis of nurse suicide in the United States between 2005 and 2016. Their analysis utilized data from the CDC's National Violent Death Reporting System. These researchers found that nurses have a greater risk of suicide than the general population. Suicide rates amongst nurses assigned female at birth (10 per 100,000) were higher than suicide rates amongst those assigned female at birth in the general population (7 per 100,000). Similarly, suicide rates amongst nurses assigned male at birth (33 per 100,000) were higher than suicide rates amongst those assigned male at birth in the general public (27 per 100,000). Nurses assigned female at birth most frequently used pharmacologic poisoning (i.e., opioids and benzodiazepines), whereas nurses assigned male at birth most often used firearms. Davidson and colleagues found no change in nurse suicide between 2005 and 2016; instead, nurse suicide has remained unaddressed for decades (Davidson et al., 2020). In 2021, Davis and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study to examine the national incidence of suicide among nurses. They found that between 2007 and 2018, 729 nurses in the United States died by suicide. More recently, Olfson and colleagues (2023) examined whether US HCPs are at greater risk for suicide than non-HCPs. They found that the suicide rate for nurses was 16 per 100,000, the second highest rate among all groups, only falling behind health care support workers (Olfson et al., 2023).

Risk Factors

Nurses must develop a keen awareness and understanding of the risk factors associated with suicide to identify individuals at risk. Assessing suicide risk should occur in all health care settings, including primary care offices, emergency departments, and outpatient clinics. Nurses must acquire the skills necessary to evaluate if an individual is in distress, depressed, in a crisis, or at imminent risk for suicide, prompting timely intervention. Risk factors include behavioral signs and symptoms that are statistically related to an individual's amplified risk for suicide. These factors may include issues related to a person's sex, race, occupation, history of abuse, environment, and other circumstances that increase their risk potential or likelihood of suicidal behavior. Individuals differ in the degree to which risk factors affect their propensity for engaging in suicidal behaviors, and the weight and impact of each risk factor will vary by person and throughout their lifespan (CDC, 2024c; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023; Soreff et al., 2023; The Joint Commission [TJC], 2019).

While a combination of situations and factors contribute to suicide risk, a prior suicide attempt is the strongest single factor that predicts future risk. The risk of dying by suicide is more than 100 times greater during the first year following an initial suicide attempt. Studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between people who reattempt suicide, those who complete it, and the timing of the reattempt. In a prospective study evaluating 371 adult patients with a suicide attempt, 19% (70 people) reattempted, and 60% of reattempts occurred within the first 6 months (Irigoyen et al., 2019; Nobile et al., 2024; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023).

While risk factors increase the likelihood of suicide, predicting who will act on suicidal thoughts remains challenging. Even among those who have risk factors for suicide, most people do not attempt suicide. However, the risk of suicide increases as the quantity of contributing factors increases (CDC, 2024c; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023; Soreff et al., 2023). Other than a prior suicide attempt, the most well-cited risk factors for suicide include the following:

- General risk factors:

- social isolation or alienation

- recent or ongoing impulsive and aggressive tendencies and/or acts

- problems tied to sexual identity and relationships

- problems linked to other personal relationships

- Environmental influences:

- low socioeconomic status

- access to lethal means, including firearms and drugs

- barriers to accessing health care and treatment

- prolonged stress, such as harassment, bullying, relationship problems, or unemployment

- stressful life events like rejection, divorce, financial crisis, other life transitions, or loss

- exposure to another person's suicide or sensationalized accounts of suicide

- Health factors:

- mental health conditions, such as:

- SUD

- bipolar disorder

- schizophrenia

- hallucinations and delusions

- personality traits of aggression, mood changes, and poor relationships

- conduct disorder

- depression

- anxiety disorders

- persons aged 18 to 25 years prescribed an antidepressant

- persons institutionalized for a mental health condition

- serious physical health conditions, including pain

- traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- mental health conditions, such as:

- Historical risk factors:

- previous self-destructive behavior

- history of mood disorder(s)

- history of alcohol and/or other forms of SUD

- family history of suicide and/or psychiatric disorder(s)

- loss of a parent or loved one through any means

- history of trauma, abuse, violence, or neglect

- certain cultural or religious beliefs tied to suicide (CDC, 2024c; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023; Soreff et al., 2023)

Special populations with an increased risk for suicide include those who identify as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) community, military personnel, and incarcerated individuals. Modifiable risk factors, such as mental health conditions, should be managed appropriately to lower a patient's risk (CDC, 2024c; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023).

Risk Factors for Nurses

There are 4.7 million practicing nurses in the United States, making them the largest group of HCPs. Nurses work in busy, fast-paced, and stressful environments. Caring for patients from birth to death and during times of wellness and illness can be one of the most rewarding jobs. Nurses often describe choosing to enter health care as a calling to serve others. However, the multiple demands on the nurse's time throughout the workday can sometimes lead to chronic toxic stress (i.e., chronic stress that results in prolonged activation of the stress response, with failure of the body to recover fully), leaving them frustrated, overwhelmed, and overextended. The nurse's inability to adequately meet all the competing demands on their time can result in burnout. When nurses experience burnout, there are negative consequences for the nurse, the health care organization, and patients. Nurses can experience physical and emotional manifestations of burnout that impact their work and home life. In addition, high rates of nurse and HCP burnout can lead to staffing concerns and turnover. Health care organizations affected by HCP burnout experience decreased quality of care and increased safety events (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2024; Clark, 2023; Jun et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2023).

Burnout

Burnout is "a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur in individuals who do 'people work' of some kind" (Maslach, 2003, p. 2). This phenomenon involves the emotional and physical exhaustion from a stressful work environment and the important responsibilities of caring for others. Maslach and Leiter (2017) expanded upon Dr. Maslach's earlier work on burnout and provided additional insights into burnout syndrome's three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and the loss of personal accomplishment. The first dimension, emotional exhaustion, is described as the first sign of burnout or burnout syndrome. Individual workers are "overextended by work demands and are depleted of physical or emotional resources…drained without any source of recovery" (p. 160). This dimension is characterized by a lack of physical or emotional energy, and an inability to deal with workplace demands or face another day on the job. The second dimension of burnout, depersonalization or cynicism, is "a negative, callous, or excessively detached response to various aspects of the job…in response to overload or exhaustion" (p. 160). Cynicism with the resulting detachment results in nurses doing just enough to get by rather than doing their best work. The third dimension of burnout, reduced personal accomplishment or inefficacy, includes "a feeling of incompetence and lack of achievement and productivity at work" (p. 160). Inefficacy can be exacerbated in a work environment that lacks adequate resources, such as supplies, equipment, and staff (Maslach & Leiter, 2017).

Compassion Fatigue or Secondary Traumatic Stress

Although burnout and compassion fatigue (CF) have some similarities, they are fundamentally different phenomena. HCPs are impacted by burnout from a stressful work environment and working conditions. In contrast, CF or secondary traumatic stress (STS) affects HCPs due to caring for victims who have experienced trauma or critical illness and death. CF is the emotional, physical, and spiritual distress resulting from caring for others. The emotional strain from caring for those who experience suffering can culminate in detachment and a loss of empathy. In addition, CF can manifest quickly, whereas burnout has a more gradual onset. HCPs suffering from CF can experience emotional and mental exhaustion, self-isolation, and lack of fulfillment in the professional setting, with similar signs and symptoms as burnout that make it hard to differentiate between the two. In addition, HCPs can experience one or both phenomena simultaneously. Nurses experiencing burnout, CF, or STS can suffer from anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. Understanding that burnout, CF, and STS can increase the risk of nurse suicide is critical to preventing self-harm or death (Clark, 2023; Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project, 2022; Garnett et al., 2023).

Protective Factors

Protective factors are key behaviors, environments, and relationships that may enhance resilience and decrease the risk that an individual will attempt suicide. Protective factors have been shown to safeguard individuals from suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Individuals differ in the degree to which protective factors affect their propensity for engaging in suicidal behaviors. Like risk factors, each protective factor's impact on suicidality varies across the lifespan (CDC, 2024c; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023). Research demonstrates that some of the most well-established suicide protective factors include the following:

- presence of adequate social support and family connections (connectedness)

- supportive and effective clinical care from medical and mental health professionals

- positive learned skills in coping, problem-solving, conflict resolution, and other nonviolent ways of handling disputes

- cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and support instincts for self-preservation (e.g., intentional participation in religious activities and spirituality)

- restricted access to lethal means, also known as protective environments (CDC, 2024c; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023; TJC, 2019)

Warning Signs

Although statistical data demonstrate that most people who die by suicide received some form of health care services within the year preceding their death, suicidal ideation is rarely detected. Nurses must take all warning signs seriously and offer appropriate support quickly. Warning signs indicate an imminent threat (i.e., within hours or days) for the acute onset of suicidal behaviors. These are indicators that the individual may be in acute danger and require help urgently. The more warning signs the individual displays, the greater their risk of suicide and the higher their need for timely assessment and intervention (CDC, 2024c; O'Rourke et al., 2023; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023; TJC, 2019). The following warning signs are correlated with the highest likelihood of the short-term onset of suicidal behaviors:

- threatening, talking, or thinking about hurting or killing oneself

- searching for ways to kill oneself, including seeking access to drugs or other lethal means (e.g., stockpiling or obtaining weapons, strong prescription medications, or items associated with self-harm)

- writing or posting on social media about death, dying, and suicide

- engaging in self-destructive behaviors, such as substance use or self-harm (CDC, 2024c; O'Rourke et al., 2023; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023; TJC, 2019)

Individuals who display these warning signs are considered high risk for suicide and warrant immediate intervention, evaluation, referral, and hospitalization. Additional warning signs and behaviors that require a prompt mental health evaluation and precautions to ensure the safety of the individual include the following:

- expressing feelings of hopelessness and a lack of purpose or reason to live

- talking about feeling trapped or in unbearable pain

- increasing the use of drugs or alcohol

- changing behavior regarding eating and sleeping (too little or too much)

- fixating on death or violence

- engaging in self-destructive or risky behaviors

- withdrawing or expressing feelings of isolation

- showing extreme or dramatic changes in mood and personality, such as acting anxious, agitated, restless, irritable, or enraged, or talking about seeking revenge

- expressing overwhelming self-blame, remorse, guilt, or shame

- feeling like a burden to others

- giving away prized possessions

- losing interest in things

- experiencing bullying, sexual abuse, or violence (CDC, 2024c; O'Rourke et al., 2023; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023)

Nurses and health care organizational leaders must recognize the signs and symptoms of burnout, CF, or STS. In addition to the warning signs listed above, additional warning signs specific to HCPs include:

- emotional and physical exhaustion

- dreading going to work or constant dread/panic while at work

- apathy towards others

- frequent absenteeism or tardiness

- negative attitude at work

- lack of engagement with friends and family, including emotional disconnection or difficulty maintaining personal relationships

- resistance to change

- poor work quality

- safety concerns with patient care

- a decreased sense of purpose

- a decline in morale (Singh et al., 2023; US Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2022)

Suicide Risk Assessment

A suicide risk assessment is a process by which an HCP gathers clinical information to determine an individual's risk for suicide. A risk assessment identifies behavioral and psychological characteristics associated with an increased risk for suicide, allowing for the implementation of effective, evidence-based treatments and interventions to reduce this risk. A risk assessment for suicide is an ongoing process, as suicidal behaviors can fluctuate quickly and unpredictably. Screening responsibilities are no longer limited to medical providers, as current health policy and suicide prevention guidelines call for the support and participation of all HCPs (i.e., physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, behavioral health specialists, social workers, and case managers), regardless of their work setting (acute or non-acute) or specialty (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2019; O'Rourke et al., 2023; Ryan & Oquendo, 2020; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023). A complete risk assessment must include the following vital aspects:

- information about past and present suicidal ideation and behavior

- information about the patient's context and history

- prevention-oriented suicide risk formulation anchored in the patient's life context (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2019; O'Rourke et al., 2023; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2023)

The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (2018) published an updated guideline, Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk, which supports two critical goals cited by the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (HHS, 2021):

- Goal 8: Promote suicide prevention as a core component of healthcare services.

- Goal 9: Promote and implement effective clinical and professional practices for assessing and treating those identified as being at risk for suicidal behaviors.

Together, the Action Alliance (2019) and the National Strategy put forth the Zero Suicide (ZS) Model, last updated in 2021, which provides a framework to coordinate a multilevel approach to implement evidence-based practices for suicide prevention. ZS encourages the screening of all patients for suicide risk on their first contact with an organization and at each subsequent encounter. The core elements of the ZS model include ongoing risk assessment, collaborative safety planning, evidence-based interventions specific to the identified risk level, lethal-means reduction, and continuity of care. Structuring a suicide risk assessment is not a straightforward task and involves asking difficult questions about suicidal ideation, intent, plan, and prior attempts. Individuals may openly respond to queries and engage in discussion, or they may be limited in their replies and offer minimal information. At times, the patient may bring up the topic on their own, but research demonstrates that this is rare (Brodsky et al., 2018; HHS, 2021; SAMHSA, 2024c, 2025b). The list below outlines the assessment of risk for suicide as compiled and adapted from the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (2018) and HHS (2021) guidelines:

- The suicide risk assessment should consider risk and protective factors that may increase or decrease the patient's risk of suicide.

- Observation and the existence of warning signs and the evaluation of suicidal thoughts, intent, behaviors, and other risk and protective factors should be used to inform any decision about a referral to a higher level of care.

- Mental state and suicidal ideation can fluctuate considerably over time. People at risk for suicide should be reassessed regularly, especially if their circumstances have changed.

- The clinician should observe the patient's behavior during the clinical interview. Disconnectedness or a lack of rapport may indicate an increased risk for suicide.

- The nurse should remain both empathetic and objective. A direct, nonjudgmental approach allows the nurse to gather the most reliable information collaboratively and encourages the patient to accept help.

To assess a patient's suicidal thoughts, the nurse should inquire directly about thoughts of dying by suicide or feelings of engaging in suicide-related behavior. The distinction between NSSI and suicidal behavior is essential. Nurses should be direct when inquiring about any current or past thoughts of suicide and ask individuals to describe any such thoughts. According to the Action Alliance (2018) and HHS (2021), a comprehensive evaluation of suicidal thoughts should include the following:

- onset (when did it begin)

- duration (acute, chronic, recurrent)

- intensity (fleeting, nagging, intense)

- frequency (rare, intermittent, daily, unabating)

- active or passive nature of the ideation ("wish I was dead" versus "thinking of killing myself")

- whether the individual wishes to kill themselves or is thinking about or engaging in potentially dangerous behavior such as cutting to relieve emotional distress

- lethality of the plan (no plan, overdose, hanging, firearm)

- triggering events or stressors (relationship, illness, loss)

- what intensifies the thoughts

- what distracts the thoughts

- association with states of intoxication (if thoughts occur only when the individual is intoxicated)

- understanding the consequences of future potential actions (HHS, 2021; National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2018; SAMHSA, 2024c, 2025b)

Evidence-Based Risk Assessment Tools for Suicide

A comprehensive suicide risk assessment must include a validated, evidence-based screening tool consisting of a set of directed questions. Evaluating the risk level and appropriate actions for each risk level is a critical aspect of suicide prevention. All nurses must understand how to perform a proper risk assessment, ascertain the risk level, and respond according to evidence-based guidelines. Several tools have been developed and are used throughout various clinical settings. Within the same facility or working environment, all staff members are encouraged to use the same tools and procedures to ensure that patients with suicide risk are identified and managed consistently. Similarly, nurses must become familiar with and comfortable using the assessment tool to elicit an open discussion with the patient. The standard of care in suicide risk assessment requires clinicians to conduct a thorough suicide risk assessment for all patients (Falcone & Timmons-Mitchell, 2018; National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2018).

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) is one of the most widely used, validated, and evidence-based instruments in suicide risk assessment and is available in 114 languages. Several versions of the C-SSRS have been developed for clinical practice. The tool is supported by extensive evidence that reinforces its validity as a screening method for longitudinally predicting future suicidal behaviors. It is a straightforward and concise tool that screens for a wide range of suicide risk factors, using direct language to elicit honest responses. The C-SSRS provides a framework to assess suicide risk and NSSI, identify the risk level, and guide appropriate action according to the risk level. The C-SSRS is endorsed by several prominent organizations, including the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, SAMHSA, CDC, World Health Organization (WHO), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH; Brodsky et al., 2018; Columbia Lighthouse Project, n.d.; O'Rourke et al., 2023; SAMHSA, 2025b).

Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T)

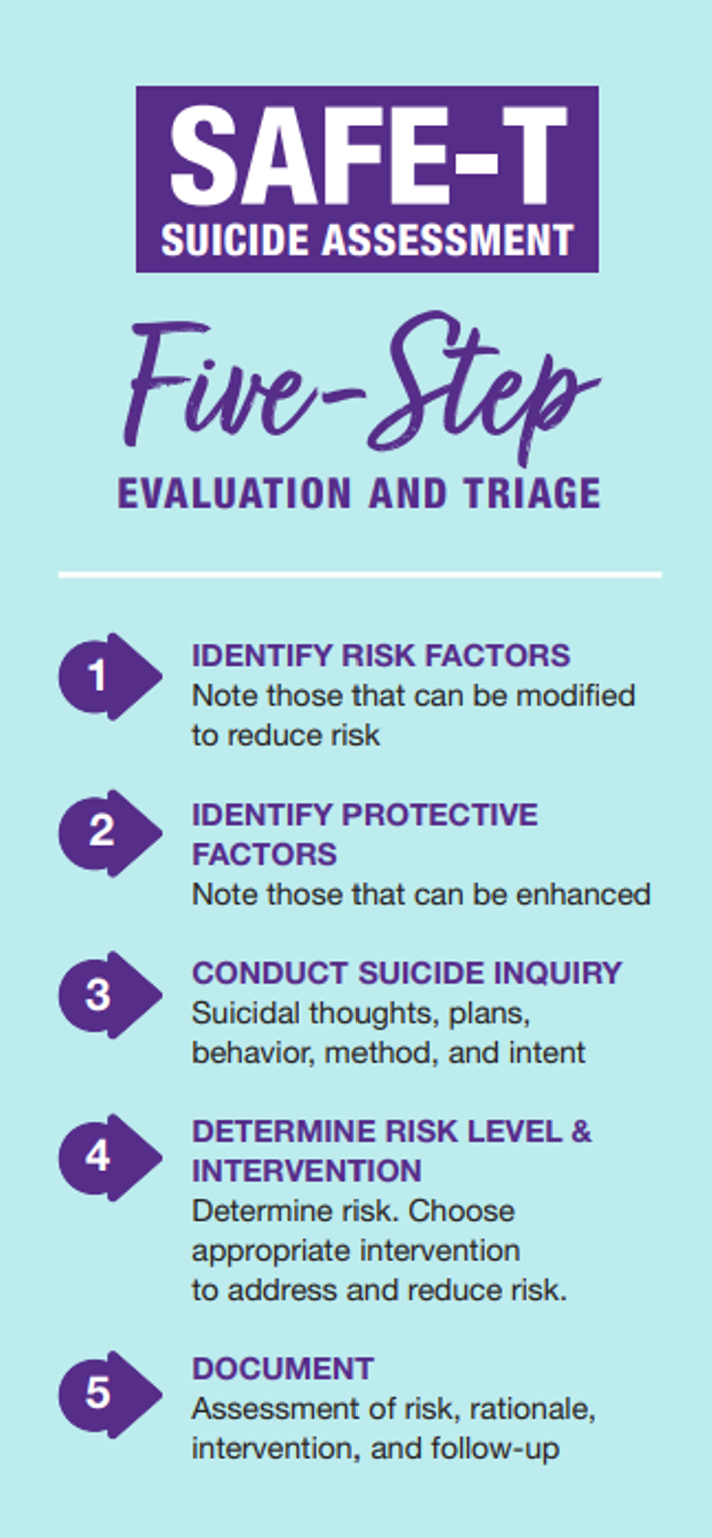

The Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T) is a tool that incorporates the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guidelines for suicide assessment and is used most commonly in emergency departments by clinicians and nurses. SAFE-T can identify risk and protective factors; inquire about suicidal thoughts, behavior, and intent; and determine the patient's risk level. It provides appropriate interventions directly to enhance safety. The five steps are outlined in Figure 1 (SAMHSA, 2024b).

Figure 1

SAFE-T Steps

According to the SAFE-T screening tool, a person's risk of suicide can be any of three levels: low, moderate, or high. These risk levels, defining features, and interventions are summarized in Table 1. Suicide precautions should be implemented whenever a patient is deemed at risk. For patients at low risk of suicide, the nurse should make personal and direct referrals to outpatient behavioral health and other providers for follow-up care within a week of the initial assessment, rather than leaving the patient to make the appointment (Columbia Lighthouse Project, n.d.; SAMHSA, 2024b).

Table 1

Level of Suicide Risk, Defining Features, and Associated Interventions

Risk Level | Features | Interventions |

|

| |

Moderate |

|

|

High |

|

|

(Columbia Lighthouse Project, n.d.; SAMHSA, 2024b)

Suicide Risk Reassessment

Reassessment of a patient's suicide risk should occur when there is a change in their condition (e.g., relapse of SUD) or psychosocial situation (e.g., the end of an intimate relationship) that suggests increased risk. Nurses should update information about a patient's risk factors when changes in their symptoms or circumstances indicate increased or decreased risk (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2018).

Suicide Prevention

Preventing suicide is the primary objective of suicide risk assessment and management. The most effective strategies focus on strengthening suicide protective factors, such as improving access to mental health services, counseling, and other psychosocial resources. Managing mental health conditions (especially mood disorders) is one of the most important interventions for suicide risk reduction and includes nonpharmacological and pharmaceutical treatments based on individual needs (NIMH, 2024). Given the long-lasting effects that suicide can have on individuals, families, and communities, the CDC has identified suicide as a serious public health problem. Suicide prevention requires a comprehensive public health approach that addresses all levels of society. By learning the warning signs of suicide, promoting prevention and resilience, and committing to social change, suicide rates can be decreased. Table 2 outlines strategies to prevent suicide (CDC, 2024b, 2024e).

Table 2

Strategies to Prevent Suicide

Strategy | Approach |

Strengthen economic support |

|

Strengthen access and delivery of suicide care |

|

Create protective environments |

|

Promote connectedness |

|

Teach coping and problem-solving skills |

|

Identify and support people at risk |

|

Lessen harm and prevent future risks |

|

(CDC, 2024b, 2024e)

The 988 Lifeline

For those with suicidal ideation, each patient and their family members should be given information to access the 988 Lifeline by calling or texting 988. Counselors are available via the national toll-free phone number, on a web-based live chat (https://988lifeline.org), by text, or through a mobile application. This service is available 24 hours a day and 7 days a week across the United States. Furthermore, individuals should also be provided with contact information for local crisis and peer support organizations (NIMH, 2024).

The 988 Lifeline lists the following three "prompt questions" that address current suicidal desire, recent (over the past two months) suicidal desire, and prior suicide attempts (NIMH, 2024):

- Are you thinking of suicide?

- Have you thought about suicide in the last two months?

- Have you ever attempted to kill yourself?

An affirmative answer to any or all of these questions requires the crisis telephone worker to conduct a full suicide risk assessment based on subcomponents that review suicidal desire, suicidal capability, suicide intent, and buffers or connectedness. Since isolation is an identified risk factor and a potential precipitant of suicide, engagement of supportive third parties is critical if endorsed by the individual at risk for suicide. Third parties should be aware of the safety plan and understand resources to ensure safety (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2018; 988 Lifeline, n.d.; SAMHSA, 2025c).

Impulsivity and Access to Lethal Means

As described earlier, firearms are the most lethal and most common method of suicide in the United States, and suicide attempts with a firearm are overwhelmingly fatal. Firearm owners are not more suicidal than non-firearm owners; instead, their suicide attempts are more likely to be fatal. The connection between impulsivity and access to lethal means dramatically enhances the risk of death by suicide. Most suicide attempts involve little planning and occur during a short-term crisis by individuals with access to lethal means. Therefore, there is a direct correlation between death by suicide and access to lethal means, such as firearms. If lethal means are made less available to impulsive attempters, and patients substitute less lethal means or temporarily postpone their attempt, the odds that they will survive increase. Studies have demonstrated that when access to a highly lethal suicide method is restricted, the overall suicide rate drops (Allchin et al., 2019; Studdert et al., 2020). The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA, 2024) states in its suicide prevention plan that a reduction in access to lethal means at the population level should be implemented as a measure of suicide prevention. This may include firearm restrictions, reducing access to poisons and medications commonly associated with overdose, and barriers to jumping from lethal heights. Such restrictions may be accomplished through lethal means safety counseling (LMSC). LMSC consists of a discussion between a nurse and a patient at risk for suicide. Firearm storage suggestions should be based on the patient's risk level. Recommendations may include storing guns and ammunition separately, using a gunlock or removing the firing pin, storing firearms in a locked cabinet or safe, disassembling firearms, or keeping them at the home of a trusted individual. The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (2018) suggests that nurses arrange and confirm the removal or reduction of any lethal means when feasible before allowing an at-risk patient to be discharged or return home. Family members or caregivers should be involved to help “suicide-proof” the environment (SAMHSA, 2025b).

Community Education

In addition to restricting access to lethal means, expanding options for nurse education and gatekeeper training has a positive impact on reducing suicide rates. Gatekeeper training was fomerly referred to as "recognition and referral training" (RRT) but is now referred to as QPR (question, persuade, refer). This refers to the critical role that individuals without formalized psychosocial training have in suicide prevention. QPR helps educate individuals across the community (e.g., teachers, coaches, emergency responders, clergy), equipping them with the skills to identify people who may be at risk of suicide. It offers training on how to respond to these individuals and refer them to support services and treatment. Training these community-based individuals on how to respond to mitigate a person's suicide risk is vital since most individuals at risk for suicide seek guidance and support from close contacts (i.e., "gatekeepers"). QPR strives to create an informed support network of people within communities equipped to connect suicidal persons with the right resources. Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST) is one of the most effective and well-cited QPR programs (QPR Institute, n.d.; SAMHSA, 2024a, 2025a).

Suicide Prevention for Nurses

Physician suicide has long been recognized as a serious concern, with various research studies focusing on prevention strategies. Traditionally, less attention has been given to nurse suicide. HCP burnout has been a recognized problem for decades and is a risk factor for depression and suicide. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought HCP burnout to the forefront of global and national priorities. In 2007, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) presented the Triple Aim framework to optimize health care system performance. The three dimensions of the Triple Aim include improving the patient care experience, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of health care. Health care organizations and national leaders have recently highlighted that a critical component to achieving the Triple Aim is the HCP's work environment. Therefore, many organizations have advocated expanding the Triple Aim to include a fourth dimension: attaining joy in work. The evolution to the Quadruple Aim addresses the importance of a healthy work-life balance for HCPs as a foundation to achieve the Triple Aim. Addressing burnout and promoting joy in the workplace can improve patient outcomes and safety, and prevent suicide among HCPs. More recently, a Quintuple Aim has been proposed, adding a fifth area of focus with the goal of advancing health equity. Proponents of the quintuple aim hypothesize that safe, high-quality care cannot be achieved without the addition of the fourth and fifth aims (Feeley, 2017; Fitzpatrick et al., 2019; Mate, 2022).

Suicide prevention is complex, requiring individual and organizational efforts. Therefore, it is more effective for nurses and healthcare organizations to implement strategies to prevent risk factors such as burnout, CF, and STS. Nurse burnout and CF can occur due to factors within the health care organization, individual factors within the nurse, or both. Health care leaders must identify and address the organizational factors that can contribute to burnout and CF in nurses. To improve their work-life balance, individual nurses also need to recognize modifiable risk factors. Various organizations, including the CDC and TJC, have put forth recommendations for improving HCPs' well-being to reduce burnout and manage fatigue and stress during times of crisis. HCPs continue to provide care despite challenging work demands, increased stress, and more complex care needs in times of crisis. Health care organizations are faced with the challenge of caring for patients while also considering the needs of their staff. Managing stress and exhaustion is a shared responsibility between the individual HCP and the health care organization. By working together, effective prevention and treatment strategies can be instituted (Hittle et al., 2020; TJC, n.d.).

Individual Strategies

Nurses must be proactive about their physical and mental health, given the risk for burnout, CF, and STS. However, real and perceived barriers often prevent nurses from engaging in physical and mental health wellness strategies. Suicide prevention for nurses starts with developing healthy coping and resilience, modifying self-perpetuated stigma, and providing self-care. First, the individual nurse must recognize the signs of burnout, CF, STS, or suicidal ideation. Nurses should identify the changes in their minds and body when they feel burnt out, depressed, or suicidal so that they can better care for themselves. Next, nurses need to embrace the concept of work-life balance. Nurses are caregivers who often put the needs of their patients ahead of their own. However, a nurse who prioritizes self-care and embraces work-life balance will be more content and able to function effectively in the workplace for a longer career (American Nurses Association [ANA], n.d., 2024). Additional strategies that nurses can use to prevent burnout, CF, or STS include (ANA, n.d., 2024; Fishbein, 2023; HHS, 2022; Williams et al., 2022):

- Improve schedules: Nurses should minimize rotating between shifts throughout the week. Also, nurses should avoid working overtime or extended shifts.

- Take breaks: Nurses should utilize their vacation time to get away from the workplace. During the workday, nurses should not skip breaks or their scheduled mealtime. Getting away from the unit for brief periods throughout the day is crucial.

- Learn to say no: Nurses naturally want to help others, which can sometimes be problematic when the nurse overextends themselves. Learning to say no and setting boundaries can prevent burnout.

- Ask for help: Nurses who notice early signs and symptoms of burnout, CF, STS, or suicidal ideation should be empowered to speak up. Making their needs known can help healthcare leaders make appropriate changes to ensure the nurse's or HCP’s well-being.

- Reignite the passion for nursing: When nurses experience signs and symptoms of burnout, CF, or STS, reflecting on why they chose nursing can be helpful. Sometimes, getting involved in a new initiative they are passionate about can change those feelings of burnout into personal accomplishment. Nurses may also consider going back to school to advance their careers.

- Seek support: Nurses should seek out support groups, buddies, or mentors that can serve as an outlet to vent frustrations or discuss challenges. Creating peer mentors encourages teamwork and collaboration, decreasing the risk of burnout, CF, or STS.

- Learn coping methods: Resilient nurses are less likely to become burned out. Therefore, effective coping is critical to HCP’s well-being. Potential approaches include breathing techniques, mindfulness, meditation, restorative exercise, journaling, and a post-work relaxation routine.

- Changing specialties or focus: One of the unique features of nursing is that there are numerous different specialty areas. If the current work environment is causing significant stress, a change of pace or setting may be necessary. Strategies could include changing units or facilities, moving from inpatient to outpatient, or changing roles.

- Prioritize physical wellness: Basic strategies could include healthy eating, regular exercise, sleeping at least seven hours per night, smoking cessation, and limiting alcohol intake. For more information, refer to the NursingCE course, Avoiding Nurse Burnout.

Organizational Strategies

Various organizations have put together evidence-based resources for communities and organizations to foster the development of suicide prevention strategies. The CDC has provided recommendations for organizations to prevent suicide (Table 2). Health care organizations must create evidence-based strategies to address screening, assessing, safety planning, and referrals for nurses at risk for suicide. An essential component of these strategies is confidentiality for nurses who report burnout, CF, STS, or suicidal ideation, and creating a culture that destigmatizes suicide. Organizational strategies should focus on system-wide changes that promote HCP wellness, self-care, and resilience. Reducing the risk of burnout, CF, and STS will decrease the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide. The Health Policy Institute of Ohio (HPIO) released an evidence-based policy brief stating that a multistakeholder approach is required to improve nurse well-being, and state lawmakers, health professional colleges and universities, health professional licensing boards, and health care leaders should all be included (ANA, n.d.; CDC, 2024b, 2024e; HPIO, 2020).

Reducing the Stigma

Organizational leaders must create a culture within the workplace that reduces the stigma associated with HCP burnout, CF, STS, or suicidal ideation. Ethically, nurses and other HCPs are taught to promote autonomy and beneficence, or doing right by others. These ethical principles apply when caring for patients and when working with colleagues. Creating a culture that promotes knowledge and positive attitudes about physical and mental wellness can be critical in addressing HCP distress and suicide risk. Health care organizations should educate their staff about the signs and symptoms of CF, burnout, and STS, and how to assess for and recognize them in patients, their colleagues, and themselves. Signs of distress can be subtle at first, but colleagues who work closely together are well-poised to notice and act on these changes. Creating a culture that promotes an open dialogue about HCP distress can normalize engagement in mental health treatment. With stigma reduction being a core component of successful wellness and suicide prevention programs, organizations must provide education, policies, and procedures to make it safe for staff to seek treatment (ANA, n.d.; Bergman & Rushton, 2023; Moutier, 2018; Wolters Kluwer, 2024).

Creating a Positive Organizational Culture

It is well documented that the organizational culture directly impacts HCPs' well-being. Therefore, healthcare organizations must create a positive organizational culture that prioritizes wellness and safety and recognizes that HCPs' well-being is everyone's responsibility (ANA, n.d.; HPIO, 2020). Some evidence-based strategies to promote a positive organizational culture include (ANA, n.d.; HPIO, 2020):

- Leadership must prioritize wellness: Health care organization executive leadership plays a critical role in creating a positive organizational culture. Health care leaders can deploy various strategies to prioritize wellness.

- Appointing a Chief Wellness Officer (CWO) demonstrates a commitment to wellness and support for HCPs. The CWO should be a member of senior leadership who is equipped with resources to support wellness initiatives.

- Ensure that all leaders in the organization improve wellness in the work environment within the scope of their role. Leaders must actively engage with their staff, listen to their wellness needs, and provide needed resources. The leaders must also role-model healthy physical and mental health behaviors.

- Open discussion and acknowledgment of the importance of HCP well-being. When HCPs feel that their values align with the values of the organization, they are more likely to engage in healthy workplace behaviors. HCPs will also be more likely to seek help when they feel that the organization is committed to their wellness.

- Psychological safety and confidential assessment and referrals: When HCPs are experiencing burnout, CF, STS, or suicidal ideation, they need to feel safe to ask for help. When HCPs perceive the work environment as punitive or not supportive of wellness, they are more likely to experience distress. Health care organizations must ensure access to confidential mental health and addiction screening, assessment, and referral programs that support access to appropriate treatment.

- The Healer Education, Assessment, and Referral (HEAR) program is an evidence-based, confidential assessment and referral program for HCPs. The American Medical Association (AMA) and the ANA recognize the HEAR program as a best practice in suicide prevention. The HEAR program educates HCPs about burnout, depression, and suicide. In addition, the HEAR program provides a confidential, online assessment of stress, depression, and other mental health conditions. After the assessment, the HEAR program offers personalized referrals to local mental health clinics and community resources.

- A just culture focuses on the accountability of individuals and the organization for patient care and safety. HCPs should be supported when they bring up safety concerns so they do not fear retribution. HCPs should also be held accountable for their decisions when assessing safety concerns. Health care organizations must create a culture that promotes honest disclosure of errors and ensures support for HCPs following an adverse event.

- Healthcare organizations should measure wellness as a quality indicator. Utilizing valid and reliable tools to measure burnout and well-being can help establish HCP wellness as a priority. This strategy allows leadership to implement effective strategies to reduce burnout and suicidal ideation, improve mental health, and evaluate these measures continuously or consistently.

- Diverse and inclusive environment: A positive work culture is one where HCPs of all backgrounds feel safe and valued. Implicit or explicit bias, when unaddressed, contributes to burnout and distress. Health care organizations often have policies on responding to discrimination but limited resources for those who experience it.

- Leadership must be committed to changing cultural norms. Leaders must be aware of bias and how to respond effectively.

- Using the Implicit Association Test (IAT) to assess individual bias can increase the understanding of HCPs on ways that bias influences their decisions.

- Increasing diversity among HCPs can create a positive diversity climate. For more information, refer to the NursingCE courses Civility in the Workplace and Implicit Bias.

Interventions to Promote Mental Health and Well-being

In addition to creating a positive work culture, organizations should focus on interventions to promote mental health and well-being and thereby reduce HCP burnout, CF, STS, and suicidal ideation. For example, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programs mitigate the signs and symptoms of burnout in nurses and other HCPs. In addition, health care organizations should create workplace environments that foster resilience and self-care for their staff. Some strategies that leadership can use to create a nurturing environment to manage burnout include (HPIO, 2020; Wolotira, 2023):

- encourage staff participation in self-care activities at work (e.g., movement, mindfulness, meditation, journaling)

- invite staff to take a break outdoors and listen to their stories

- have crucial conversations with staff about the signs and symptoms of burnout

- diversify or decrease staff workload

- support staff in having time off, including vacations

- encourage participation in debriefing after traumatic events

- provide positive recognition of staff

- acknowledge and recognize the loyalty of staff members

- promote peer support, teamwork, and collaboration

- empower staff in professional development

- support employee autonomy

References

Allchin, A., Chaplin, V., & Horwitz, J. (2019). Limited access to lethal means: Applying the social-ecological model for firearm suicide prevention. Injury Prevention, 25, 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2018-042809

American Association of College of Nursing. (2024). Nursing workforce fact sheet. https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-data/fact-sheets/nursing-workforce-fact-sheet

American Association of Suicidology. (2025). USA suicide: 2023 official final data. https://jmcintos.pages.iu.edu/2023datapgsv1a.pdf

American Nurses Association (n.d.). Nurse suicide prevention/resilience. Retrieved April 2, 2025, from https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nurse-suicide-prevention

American Nurses Association. (2024). What is nurse burnout? How to prevent it. https://www.nursingworld.org/content-hub/resources/workplace/what-is-nurse-burnout-how-to-prevent-it

Bergman, A., & Rushton, C. (2023). Overcoming stigma: Asking for and receiving mental health support. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 34(1), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.4037/aacnacc2023684

Brodsky, B. S., Spruch-Feiner, A., & Stanley, B. (2018). The zero suicide model: Applying evidence-based suicide prevention practices to clinical care. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(33). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00033

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). Facts about suicide. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024b). Preventing suicide. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/prevention/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024c). Risk and protective factors for suicide. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/risk-factors

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024d). Suicide data and statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/data.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024e). Suicide prevention resource for action. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/resources/prevention.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Health disparities in suicide. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/disparities

Clark, E. (2023). What is nurse burnout? NurseJournal. https://nursejournal.org/resources/nurse-burnout

Columbia Lighthouse Project. (n.d.). SAFE-T with C-SSRS. Retrieved April 2, 2025, from http://cssrs.columbia.edu/documents/safe-t-c-ssrs

Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project. (2022). What is compassion fatigue? https://compassionfatigue.org/index.html

Davidson, J. E., Proudfoot, J., Lee, K., Terterian, G., & Zisook, S. (2020). A longitudinal analysis of nurse suicide in the United States (2005–2016) with recommendations for action. Worldviews of Evidence-Based Nursing, 17(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12419

Davis, M. A., Cher, B. A. Y., Friese, C. R., & Bynum, J. P. W. (2021). Association of US nurse and physician occupation with risk of suicide. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(6), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0154

Dutheil, F., Aubert, C., Pereira, B., Dambrun, M., Moustafa, F., Mermillod, M., Baker, J. S., Trousselard, M., Lesage, F. X., & Navel, V. (2019). Suicide among physicians and healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 14(12), e0226361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226361

Falcone, T., & Timmons-Mitchell, J. (2018). Suicide prevention: A practical guide for the practitioner. Springer Publishing.

Feeley, D. (2017). The triple aim or quadruple aim: Four points to help set your strategy. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/the-triple-aim-or-the-quadruple-aim-four-points-to-help-set-your-strategy

Fitzpatrick, B., Bloore, K., & Blake, N. (2019). Joy in work and reducing nurse burnout: From triple aim to quadruple aim. Advance Critical Care, 30(2), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.4037/aacnacc2019833

Garnett, A., Hui, L., Oleynikov, C., & Boamah, S. (2023). Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1336). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10356-3

Health Policy Institute of Ohio. (2020). A call to action: Improving clinical well-being and patient care and safety. https://www.healthpolicyohio.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CallToAction_Brief.pdf

Hittle, B. M., Wong, I. S., & Caruso, C. C. (2020). Managing fatigue during times of crisis: Guidance for nurses, managers, and other healthcare workers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2020/04/02/fatigue-crisis-hcw/?deliveryName=USCDC_170-DM24834

Irigoyen, M., Porras-Segovia, A., Galvan, L., Puigdevall, M., Giner, L., De Leon, S., & Baca-Garcia, E. (2019). Predictors of re-attempt in a cohort of suicide attempters: A survival analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 247, 20-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.050

Jun, J., Ojemeni, M. M., Kalamani, R., Tong, J., & Crecelius, M L. (2021). Relationship between nurse burnout, patient and organizational outcomes: Systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 119(2021), 103933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103933

Maslach, C. (2003). Burnout: The cost of caring. Malor Books.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2017). New insights into burnout and health care: Strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Medical Teacher, 39(2), 160–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248918

Mate, K. (2022). On the quintuple aim: Why expand beyond the triple aim? https://www.ihi.org/insights/quintuple-aim-why-expand-beyond-triple-aim

Mental Health America. (2022). The mental health of healthcare workers. https://mhanational.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Mental-Health-Healthcare-Workers.pdf

Moutier, C. (2018). Physician mental health: An evidence-based approach to change. Journal of Medical Regulation, 104(2), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.30770/2572-1852-104.2.7

Moutier, C. (2024). Suicidal behavior. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/psychiatric-disorders/suicidal-behavior-and-self-injury/suicidal-behavior

National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. (2018). Recommended standard care for people with suicide risk. https://theactionalliance.org/resource/recommended-standard-care

National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. (2019). Best practices in care transitions for individuals with suicide risk: Inpatient care to outpatient care. https://theactionalliance.org/resource/best-practices-care-transitions-individuals-suicide-risk-inpatient-care-outpatient-care

National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Suicide prevention. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/suicide-prevention/index.shtml#part_153179

National Institute of Mental Health. (2025). Suicide. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml

988 Lifeline. (n.d.). 988 lifeline. Retrieved April 2, 2025, from https://988lifeline.org

Nobile, B., Jaussent, I., Kahn, J. P., Leboyer, M., Risch, N., Olie, E., & Courtet, P. (2024). Risk factors of suicide re-attempt: A two-year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 356, 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.04.058

Olfson, M., Cosgrove, C. M., & Wall, M. M. (2023). Suicide rates of health care workers in the US. JAMA Network, 330(12), 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.15787

O'Rourke, M. C., Jamil, R. T., & Siddiqui, W. (2023). Suicide screening and prevention. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531453

QPR Institute. (n.d.). Question. Persuade. Refer. Retrieved April 2, 2025, from https://www.qprinstitute.com

Ryan, E. P., & Oquendo, M. A. (2020). Suicide risk assessment and prevention: Challenges and opportunities. Focus: The Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry, 18(2), 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20200011

Schreiber, J., & Culpepper, L. (2023). Suicidal ideation and behavior in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved March 29, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/suicidal-ideation-and-behavior-in-adults

Singh, R., Volner, K., & Marlowe, D. (2023). Provider burnout. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538330

Soreff, S. M., Basit, H., & Attia, F. N. (2023). Suicide risk. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441982

Studdert, D. M., Zhang, Y., Swanson, S. A., Prince, L., Rodden, J. A., Holsinger, E. E., Spittal, M. J., Wintermute, G. J., & Miller, M. (2020). Handgun ownership and suicide in California. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(23), 2220–2229. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1916744

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024a). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2023 national survey on drug use and health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt47095/National%20Report/National%20Report/2023-nsduh-annual-national.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024b). SAFE-T suicide assessment five-step evaluation and triage. https://library.samhsa.gov/product/safe-t-suicide-assessment-five-step-evaluation-and-triage/pep24-01-036

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024c). Zero suicide toolkit. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/zero-suicide-toolkit

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2025a). Applied suicide intervention skills training (ASIST). https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/dbhis/applied-suicide-intervention-skills-training-asist

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2025b). Columbia suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/dbhis/columbia-suicide-severity-rating-scale-c-ssrs

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2025c). National strategy for suicide prevention implementation assessment report. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/dbhis/national-strategy-suicide-prevention-implementation-assessment-report

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2025d). QPR (question, persuade, refer) suicide prevention training. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/dbhis/qpr-question-persuade-refer-suicide-prevention-training

Sudheimer, E., Ervin, D., Gerrie, J., Glass, T., May, K., Steward-Tiesworth, C., Szczechowski, K., Wodwaski, N. (2024). Understanding the silent crisis: Suicide among nurses. https://www.myamericannurse.com/understanding-the-silent-crisis-suicide-among-nurses

The Joint Commission. (n.d.). Worker well-being resources. Retrieved April 2, 2025, from https://www.jointcommission.org/our-priorities/workforce-safety-and-well-being/resource-center/worker-well-being

The Joint Commission. (2019). Suicide prevention. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/suicide-prevention

Tiesman, H., Weissman, D., Stone, D., Quinlan, K., & Chosewood, C. (2021). Suicide prevention for healthcare workers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2021/09/17/suicide-prevention-hcw

United Health Foundation. (n.d.). Teen suicide in the United States. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/teen_suicide

US Department of Health & Human Services. (2021). The surgeon general's call to action to implement the national strategy for suicide prevention. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/sprc-call-to-action.pdf

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Addressing health worker burnout. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/health-worker-burnout/index.html

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2024). 2024 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. https://news.va.gov/137221/va-2024-suicide-prevention-annual-report

Williams, S. G., Fruh, S., Barinas, J. L., & Graves, R. J. (2022). Self-care in nurses. Journal of Radiology Nursing, 41(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jradnu.2021.11.001

Wolotira, E. A. (2023). Trauma, compassion fatigue, and burnout in nurses: The nurse leader's response. Nurse Leader, 21(2), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2022.04.009

Wolters Kluwer. (2024). Five opportunities for health administrators to change the narrative around suicide stigma. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/five-opportunities-health-administrators-change-suicide-stigma

Powered by Froala Editor